![]()

1

Intimate Communiqués

Melchior Lorck’s Flying Tortoise

Marina Warner

The bird’s-eye view gives a vantage point of great power; from this height and synoptic angle, hitherto unknown experiences and information can be unified and displayed. Paradoxically, however, this heroic and often vast vision can also give access to small, personal glimpses of private scenes, and so become a vehicle for gaining entry to secrets – and for transmitting intimate communiqués to the viewer. Furthermore, an aerial viewpoint defies the laws of time and space, and gives the narrator a chance to fly free of these constraints. It is significant that the Tales of a Thousand and One Nights, which were first translated in Europe by the French scholar Antoine Galland at the beginning of the eighteenth century, associate such views from above with the power and knowledge of flight, brought about on behalf of humans by magic – either by djinn or by enchanters’ devices. The vantage point magic makes possible grants the flyer superior powers – to see farther, to know and control more. The magic carpet, which figures in some of the tales, acts as a vehicle for the characters’ transport – in both senses, as travel and as rapture; and it has since been established as the pre-eminent figure – the richest and most versatile metonym – for the workings of the imagination itself. On the part of the narrator in the story (and beyond him or her stands Scheherazade, who is telling all), the carpet bodies forth a literal, dream pun on flight of fancy on the one hand, and the rush of enhanced knowledge – enlightenment – on the other. More generally it also comes to stand for the book, play or film, in relation to its readers or audience, for they themselves become transported on a fantastic journey alongside the heroes of the adventure – a journey which is sometimes airborne at a distance.

Such aerial mobility, providing a common ideal vantage point to pursue a narrative and communicate its free play with time and place, functions analogously to the omniscient third-person point of view, above the action and detached from it. But at the same time, with startling flexibility, it can also imply a single observer, a first-person perceiver who is uniquely, almost prophetically, equipped to see all. It operates in the manner of the generalised eye of fate, oracular and god-like, but can also slip into the persona of an individual questor, even a peeping Tom, who is able to uncover things normally hidden from view.

The exhibition of the Indian epic, the Ramayana, held in the British Library in London between May and September 2008, showed this tradition at work in the story scrolls that unfold the complex and multifarious episodes of the sacred epic.1 The most remarkable sequence of all, in what was a dazzling exhibition about visual narrative, was painted by Sahib Din and his studio in the reign of Jagat Singh in the mid-seventeenth century. At numerous points in the adventures, the painter-storyteller rises above the scene to create the picture, and to do so he combines two vantage points: one oblique to the action, the other airborne, as in one scene when the travellers stop for the night, and lay their rugs on the ground. From above, the viewer can see the divine Rama and Sita side by side on the right, but the horses beneath them are painted in profile, as is the cart and their departure the next day on the left. Many other scenes similarly offer a double viewpoint, one sharing the plane of the characters, the other floating disconnected from the earth above the mêlée. The compositions cannot be attributed to lack of skill – though they can be to an absence of Renaissance perspective – but they convey a keenly experienced desire to follow, by means of visual devices, the fluid motion of stories. The language of cinema would later describe these narrative manoeuvres as crane shots, panning shots and long distance sweeps (interestingly, the Indian epic artists include no close-ups).

This magnificent Ramayana cycle makes an illuminating comparison with contemporary European narrative arts and their use of viewpoint; it reveals how, alongside the geometry of perspective and observer, as established in Western art, artists elsewhere were multiplying positions and entry points into a drama, giving them freewheeling mobility in handling a story.

The Danish-born artist Melchior Lorck (1526–7–after 1588) travelled to Turkey in 1555–9 to gather information for his patron, Ferdinand I, heir to the Holy Roman Emperor; his stay in the Ottoman empire makes him an invaluable early witness, so it is surprising that he has been so little explored – the catalogue raisonné of his work was published only recently.2 The art of this sixteenth-century traveller does not focus on flying as such, but has frequent recourse to an elevated position – the better to report on the mysterious realm of Islamic power. One of the first Western European observers to travel in the region and record what he was observing in visual, artistic form, Lorck was producing intelligence about the power and culture of the threatening rival Ottoman empire; his numerous drawings and prints give an unprecedented and often proto-Surrealist record of Turkish customs, architecture, costumes and devices. Lorck’s prime intention being to draw up an inventory of data and communicate it clearly, he adopted the omniscient narrator’s view from above for several key works. One of his greatest creations is the vast, synoptic ‘Prospect of Constantinople’, a panoramic watercolour drawing of the city of Istanbul, but two other pieces reveal the intimate communiqués which the aerial view can also achieve: in a superb drawing surveying the roofs of Istanbul from the artist’s lodgings, he discovers a pair of lovers on a balcony; and in one of his many prints, he flies over Mecca to disclose the arrangement of the shrines inside the sacred precinct.

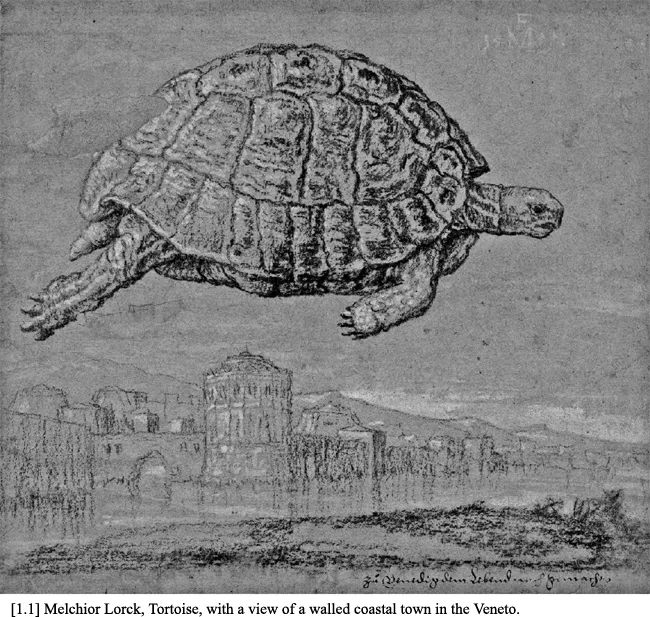

Lorck drew the first scene from life, but imagined the second. In literature composed before the invention of flight, the use of the aerial view frequently serves narrators who want to reveal intimate information to the reader. Born a year or two before Dürer died, Lorck was an attentive and admiring apprentice, and drew a powerfully severe portrait of his great predecessor. Besides emulating the scrutinising accuracy of Dürer, Lorck also had a quirky, even comic imagination, and a taste for odd juxtapositions and discrepancies of scale: a superb sketch, now in the British Museum, reveals his scientifically objective zoological interests, but he has transformed a tortoise into an object of wonder by positioning the animal in the sky above a Venetian coastal scene (Figure 1.1). Lorck has also added the sly inscription ‘Made in Venice from Life’. To all intents and purposes like a tortoise, the creature has been identified by the cataloguers as a certain species of turtle from the Venetian lagoon, though its paws do not resemble flippers but rather the claws of the terrestrial species.3 In any case, with such a legend, the artist dares the viewer to see the creature flying overhead like some kind of colossal, fabulous, reptilian version of the giant Rukh, the huge raptor from the Arabian nights who lifts Sinbad and can also carry off an elephant. Lorck does not give an aerial view here, though he invites his viewers to imagine the tortoise’s view of the city below. But other works of his reveal that for him an elevated vantage point served both the purposes of intimate disclosure and of synoptic sweep or overview.

Melchior Lorck was born in Flensburg in Schleswig-Holstein, which was under the Danish king at the time of his birth. Called by the well-to-do Lorcks after one of the Magi (his brothers were Caspar and Balthasar), Melchior was slender and charming-looking (angelic, even, if his self-portrait serves), well educated, peripatetic and versatile. Trained as a goldsmith in Lübeck, and polished in Italy on a Grand Tour subsidised by the Danish king Frederick II, he liked to turn his hand to any kind of art – portraits, maps, prospects, engineering charts, medals, triumphal arches, emblems, calligraphy, heraldry, bestiaries, religious caricature and propaganda. In demand in his lifetime all over Europe, patronised by kings and emperors, he remained a footloose cosmopolitan and anxious to advance: he enjoyed adding exquisitely penned curlicues to his family coat of arms, granted by the Emperor for services rendered.

Lorck first emerges clearly in 1555 when he was attached to the embassy of Augier Ghiselin Busbecq (1522–92), who was being sent by the Emperor-elect, Arch-Duke Ferdinand I, to negotiate with the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (also known as Suleiman the Lawgiver) in an attempt to prevent the sultan’s continuing assaults across the border to his Western European neighbours in Hungary and Austria. The Hapsburgs in Vienna ruled the vast possessions of the ancient Holy Roman Empire; contiguous to them, the Ottomans – under Suleiman the Magnificent and later under Suleiman II – held power over an immense territory that ranged from Armenia in the east to North Africa in the south. Suleiman had laid siege to Vienna in 1529 and been beaten back, but the vulnerability of the empire was a continued pressing matter, and the mission of 1555 aimed to negotiate greater stability. (Incidentally, this was the journey that first brought back the tulip – and the lilac. It named the first flower after the Turkish word for turban, possibly because the Turks wore the flower in their headgear, and when a traveller pointed to the flower to ask what it was, the dragoman, or interpreter, thought he must be inquiring after the turban and so the word was switched, and stuck.)4 But unlike the diplomats, who returned home, Lorck stayed on another four years until 1559, enduring hardships and troubles, which he reported in bitter complaints and lamentations to his patrons.

Melchior Lorck’s time in the Ottoman empire was the longest visit made by any artist from Western Europe during a period when the two great powers in Europe co-existed in a permanent state of live tension and perpetual conflict, and he produced a fabulously rich and rare catalogue of the customs, technology, costumes and – above all – the military arrangements of the Turks. His project presents an astonishing album of reconnaissance material: Lorck successfully compiled the detailed and acute report of an enterprising spy, a proto-photo journalist’s open-eyed output and at the same time created a marvellous work of bizarre imagination. His drawings show him to be highly responsive to aesthetic ornament, and display a penchant for bizarre poses and elaborate gestures. In these last, the influence of the Mannerist Italians, among whom the Northern European Melchior Lorck went to study, can be seen.

Lorck’s oeuvre is surprising for many reasons: first, that it is so little known, indeed almost unknown; second, that his Ottoman hosts gave him such a freedom of access and movement in their military encampments, places of worship and, it seems, even their harems; and third, that the spirit of his observations of Turkish culture and Islam departs so categorically from the approach we now know as ‘Orientalism’. For all his flamboyant fantasy, Lorck is not an Orientalist in that sense: he observes, but does not slaver or condemn. He was gathering information about the Ottomans in order to understand them and pass it on to his Hapsburg patrons, in order to help them resist Ottoman power.

When the embassy reached Constantinople, the party was put up in the Austrian emperor’s embassy near the forum of Constantine, but under reportedly uncomfortable conditions – Lorck referred to their imprisonment.5 Indeed, on arrival, the diplomatic party was held for a year and a half under house arrest in the caravanserai of Elçi Hani in Constantinople near the Atik Ali Pasha Mosque; Busbecq showed great talent in enduring this and eventually extricating a treaty (the English did not risk a mission until 1583).

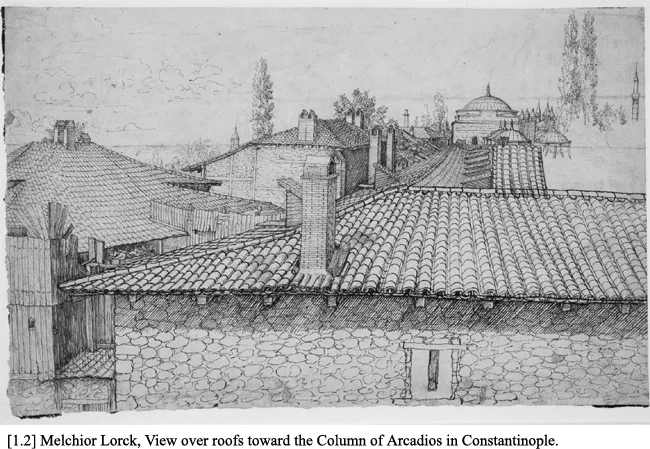

During their confinement, the artist drew the view from his room in the eaves: a detailed pen-and-ink drawing shows some of the landmarks of the great city – the Column of Arcadios in the distance (a monument from the Byzantine era, now lost), as well as the Sea of Marmara on the horizon, where Busbecq reported he could ‘see the dolphins leaping and sporting in the water’6 (Figure 1.2). This work is one of the very few original drawings to survive from Lorck’s stay in Turkey, and it is a very fine, unshowy, exemplary act of meditative attention by a new arrival in another country.

The artist’s eyes scan the scene laid out before him apparently as it lay beneath his gaze; he does not compose it to conform with a pastoral landscape or a structured cityscape, but commits it dispassionately to paper, recording the mortared stonework on the wall facing him, a blank expanse except for one small window and a brick chimney stack almost in the middle of the view. His admiration for Dürer again shows in the penmanship and detail of his attention – to the masonry, the woodwork, the rendering, to the curve and irregular tiling of rooftops and shallow domes of the adjoining mosque’s madrasa, and to the shuttered mansard windows which were built to face the prevailing wind from the sea and freshen upper floors in hot weather. He records the various palings and fences and screens erected between the buildings, some even bristling fanwise from the top of one fence, which has been raised on top of another. The whole drawing gives a virtuoso inventory of different building fabrics and textures, of what amounts to a series of screens or veils. It is a view of a view that is turning away from the viewer: a portrait of a scene that has brought its hands instinctively to cover its face or wants to present its back.

Busbecq reported wearily that the embassy building was

open to all the breezes and is therefore regarded as a healthy place of residence; the Turks, however, grudging such amenities to foreigners, not content with having blocked the view with iron bars on the windows, have added parapets, which impede both the view and the free enjoyment of fresh air. This appears to have been done in deference to the complaints of the neighbours, who declared they had no privacy from the gaze of the Christians.7

Lorck was probably trying deliberately to overcome these constraints when he looked out of the window, or perhaps his curiosity had been aroused by them; then, as his cartographer’s eye sweeps over the view below his window, his hand follows and he captures in a tiny vignette a couple making love on a terrace screened by rushes (Figure 1.3).

The striking quality of the drawing comes from the inconsequentiality of Lorck’s treatment: the temperature of...