1

Achaemenid Imperial Architecture: Performative Porticoes of Persepolis1

Margaret Cool Root

1.1 Map of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, with geographical coordinates of the DPh takht superimposed.

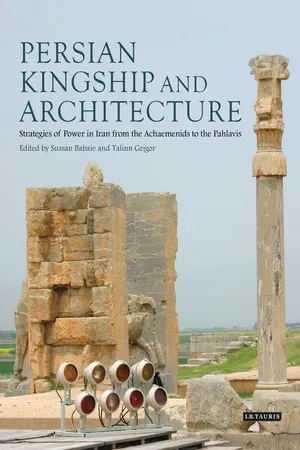

THE Apadana in Persepolis, with its elevated vista-valenced porticoes replete with figural reliefs and its imposing hypostyle hall, has iconic status as an architectural manifestation of the great empire of the Achaemenid Persians under Darius I ‘the Great’ (r. 522–486 BCE) (fig. 1.1, plate 1.2). Refined perspectives based on new empirical research on many fronts, as well as fresh possibilities in approaches to old problems, encourage me to explore the prospects of a richer understanding of this particular monument and thus of Persepolis, of Achaemenid kingship and of the empire – all of which it has so often seemed to stand for in a generalized way. My discussion here will not be an effort in Achaemenid architectural history sensu stricto;2 I will instead offer an interpretive analysis of the setting, plan, orientation, foundational metaphors and superstructure of the Apadana. My goal will be to propose ways in which the monument and its setting (within both a built and a natural landscape) engaged the mindful gaze and activated the physical experiential collaboration of participants in its presence so as to mold, to reinforce and perpetually to negotiate meanings. I hope this foray will be useful to those who contemplate the workings of imperial architecture broadly, along with those concerned specifically with Iran across time.

David Morgan discusses ‘the cultural work that images do in constructing and maintaining (as well as challenging, destroying, and replacing) a sense of order in a particular place and time’.3 In a somewhat similar vein, I aim to suggest what the ‘cultural work’ of the Apadana was meant to be, and how many of its essential features operated as an active tactic for carrying out that cultural mission. Paradoxically perhaps, part of the cultural work it was meant to do (or was scripted to do) was to express a carefully designed, highly charged ambiguity and to elicit a push–pull of multivalent reaction. The Apadana, we find, was bound up in acts both of place-/space-making and place-/space-experiencing as reciprocal social performance. It was meant to engage multiple audiences and participants visually, spatially, psychologically and spiritually in a dialogue about kingship, dynasty and imperial family. This dialogue arced across its entire environmental landscape temporally as well as experientially.

One meta-agenda here situates the Apadana within interdisciplinary discourse on performativity, inviting the reader to consider its potential for adding to that conversation. Performativity as a term and an idea occupies contested theoretical terrain, with various competing applications. It is not widely drawn into studies of ancient Near Eastern visual culture, although it has gained some traction in Egyptology. Zainab Bahrani does, however, discuss one notion of it with reference to the ancient Near East, framing her use of the term around Derrida’s rather oblique definition as a ‘communication which does not essentially limit itself to transporting an already constituted semantic content’.4 At the risk of seeming banal, I might suggest that this could be translated for our purposes to imply a communication for which meaning is fluid within certain parameters of cultural understandings and is largely (but not exclusively) dependent upon charismatic contingencies of presentation and reception, often in active social settings. The crucial idea I want to develop here in abstract terms is this: that things, representations and spaces can themselves be considered ‘communications’ and can be dealt with as active agents. Active agents, in this context, are elements that give out and also receive meanings. Such meanings are socially negotiated and are dynamically unstable. This brand of performativity is related to social-performance theory. Towards the end of this chapter we will reach back to such investments as we populate the Persepolis landscape with human dimensions of ‘social life as performance’ operating on various planes of spatial experience in this setting.5

A closely related meta-agenda places the Apadana in dialogue with recent interpretive strategies in the study of Safavid Isfahan, which, through their implicit deep engagement with notions of performativity as an abstraction within an explicated discourse on imperial performance, have inspired me to think more and somewhat differently about Achaemenid architecture.6

Backdrop: Parsa as a Place and as a Cultural Notion

The setting for our exploration is the place named Parsa by the ancient Persians. This word is Old Persian both for the land of Persia and for the city itself. Thus the name of city was conterminous with a larger concept of regional locus and cultural identity around Persianness. In modern Persian the word becomes Fars, designating to this day the region of south-western Iran that embraces ancient Parsa; the word parsa lives on, coming to mean ‘pious’. It is, of course, the place Westerners call by the Greek name Persepolis, meaning ‘city of the Persians’. Although I will perpetuate the Western-centric nomenclature because it is so engrained in the literature, I hope the reader will bear in mind the richer nuances carried by Parsa.

The ancient insistence on a triplicate invocation of Persianness (and what various things this iterative invocation may have meant) is important to our interpretation of Parsa/Persepolis as a whole and of its hallmark architectural feature of elevated porticoes. Recent investigations into the nature of Persian acculturation in south-western Iran in the early (pre-empire) centuries of the first millennium BCE show the complexity of social experience in the region between the relative-newcomer Persians and the indigenous Elamites (who were entrenched in Fars as well as in Khuzestan to the west near the Persian Gulf).7 The quintessential ‘Persian’ founder of the empire, Cyrus II ‘the Great’ (...