![]()

PART 1

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times: 1985–1995

![]()

1

Georgia: A Divided Nation

Stand where Kekelidze, Varazis-khevi, and Melikishvili Streets intersect with Chavchavadze Avenue. It is a busy crossroads where the fashionable residential district of Vake merges with downtown Tbilisi. Compare it today (2011) with the scene 20 years ago. The Soviet Academy of Sciences bookshop on Chavchavadze Avenue has gone. It has been replaced by a café, its colorful tables spilling onto the pavement. The Georgian Tea House on Melikishvili Street is now a betting shop (Maxbet). Walk a little further on Chavchavadze Avenue and you will see New Trends, Giordano, and the Acid Bar. You can still wait for a bus or improvised taxi at the intersection, but the smoky Icarus buses from Hungary have gone, replaced with a shiny new fleet financed by the Dutch. Tbilisi State University, an imposing neoclassical structure and former Tsarist Gymnasium on the corner of Chavchavadze Avenue and Varazis-khevi Street, has acquired a fancy new fence around its grounds. Outside the fence, the public telephones – reduced to one in 2010 and none in 2011 – work with cards bought with Georgian lari (GEL), not with the old two kopek pieces. But hardly anyone uses public phones because there are now 2.755 million cell phone users in a population of 4.5 million.1 And the expensive Mercedes, Volvos, and Hummers crossing the intersection are quite different from the habitual Zhigulis made in Togliatti, USSR, that used to ply this city. As before, nobody pays much attention to traffic rules, but paradoxically, with the arm-waving traffic policemen gone (they were replaced by a system of highway police patrols in August 2004), there is less chaos.

But the marks of Georgia’s transformations over the last 20 years are mixed in with relics and habits of the past despite the Rose Revolutionaries’ attempt to erase them, and it makes one ponder the degree of change. Georgia’s transition, despite the glamour of youthful leaders, mushrooming hotels, and plate-glass shops – building permits in Tbilisi trebled between 2004 and 2007 – remains at the crossroads where new claims, imported ideas, iconic styles and modern values feed into and combine with old habits, inertia, cultural traditions, and antimodernist sentiments. The result is a multi-layered palimpsest, modern, optimistic, and entrepreneurial on the top, but poor, traditional, and traumatized underneath. This is exemplified by the newly painted pastel fronts of Rustaveli Avenue and the garish waterfront hotels in Batumi that celebrate impressive investment but conceal the struggling populations that live beyond the city center. The result of this split personality – common to many transitional societies – is a dual democracy, a dual economy, and a widening chasm between urban and rural, haves and have-nots, English speakers and non-English speakers, young and old, employed and unemployed.

On the eve of the Rose Revolution in November 2003 – the third political metamorphosis since 1990 – Georgia was suffering from incessant crises. The collapse of the USSR in 1991, and turmoil under the leadership of Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1990–2), was a period of mass hysteria during which Georgia descended into a hellish version of its own fragmented past. After 1992 and the return of Eduard Shevardnadze, despite calls for radical modernization, there was no reconciliation commission or purge of former communist officials. Rather we saw a return to a reincarnated property-owning nomenklatura, and the convergence within state structures of the criminal and political, the public and the private. David Stark refers to this as ‘recombinance’, or the rebuilding of organizations ‘not on the ruins but with the ruins of communism’.2

Eduard Shevardnadze, who dominated Georgian politics from 1972 to 2003, with a short interlude in Moscow from 1985 to 1992, reconstituted power the way he knew best. He retained former Communist party members alongside younger technocrats and a sprinkling of reformers, a political mix he was convinced he could control, but that failed to introduce the desperate remedies that Georgia required. Shevardnadze’s emphasis on stability and consolidation was welcome, but by the late 1990s economic reforms had petered out. In his last years in office, central power languished, sapped by intrigue, corruption, unsolved murders, and an empty treasury. The administration was unable to construct a well-ordered state, a problem exacerbated by the unresolved conflicts on Georgian territories, and by old mental habits. It was not until November 2003, under the ambitious Mikheil Saakashvili, a Georgian jeremiad who cites Kemal Ataturk and Charles de Gaulle among his models, that the symbolic revolutionary break with the past – what Juan Linz terms transition by ‘rupture’ – took place.3 The Rose Revolution, as it was called, was led by neophytes and iconoclasts who appealed to the traditions of the past, but set about destroying the last vestiges of Soviet power. President Saakashvili, a consummate PR practitioner and politician, has not only transformed Georgia’s political (and urban) landscape, but has also reinforced traditional patterns of state dominance.

REVOLUTION AND DEMOCRACY

Vladimir Lenin, despondent, mute, and fearful that the Bolshevik experiment had gone awry, wrote in 1923:

Our state apparatus is so deplorable…that we must first think very carefully how to combat its defects, bearing in mind that these defects are rooted in the past, which, although it has been overthrown, has not yet been overcome…4

He was expressing the dilemma of all revolutionaries. They are forced, as Benedict Anderson puts it, to employ ‘the wiring of the old state’.5 In post-imperial states, old institutional wiring shapes the new. The problem is compounded when new wiring has to be installed ‘from scratch’. In this sense, as Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan have suggested, post-Soviet states were worse off than many of the ‘new democracies’ in Latin America and South Asia. The latter, though burdened by strong militaries, had the benefit of socially embedded institutions and a basic acquaintance with the open market.6 Post-communist transitions, with a barren history of institutional independence and economic pluralism, faced far more complicated tasks of state and democracy-building and, in Georgia’s case, the old imperial power was on its doorstep.

Democracy in Georgia highlights the concept’s multiple meanings. It is politically liberal in appearance but often illiberal in practice. The rhetoric of President Saakashvili, with its mix of raw populism and liberal sensibility, echoes this ambivalence. It is impossible to define Saakashvili either as a liberal or a pugnacious nationalist. He is both. He represents a country in political and economic flux. It remains psychologically lodged between the rubble of the old and the foundations of the new. Democratic structures sit alongside old regime habits and institutions. Georgians want their religion, their traditions, their heroic past, their patrons, and a powerful president tough on crime, but they also want to be ‘European’, modern, and culturally sophisticated. Georgia’s five-cross flag, introduced in 2004, is a symbol of the country’s new religious identity. It flutters alongside the starry flag of the European Union above all Georgia’s public buildings, expressing Georgians’ persistent cultural dualism.

The discovery of fossilized skulls, 1.7 million years old, in Dmanisi, Georgia, sent Georgians into a frenzy. Stenciled images of ‘Zezva’ and ‘Mzia’, as these newly imagined first European settlers were nicknamed, proliferated on Tbilisi’s walls. Dmanisi ‘proved’ that the earliest human settlers in Europe were in Georgia. President Saakashvili claimed that Georgians were ‘ancient Europeans’.7 But Georgian politics, if it is European, is so in all its contradictory splendor. Central to European history is the struggle between democracy and the state, between national minorities and majorities, wars with neighbors over territory and sovereignty, and revolutionary regimes undermining popular power. This may not be the Europe Georgians have in mind when they talk of shared values, but this is Georgia, a complex south-eastern corner of Europe where struggles over the state, democracy, and citizenship are unfinished echoes of Europe’s own battles.

Under Gamsakhurdia, democracy’s failings derived from a simplistic belief in sovereign statehood and majority rule; under Shevardnadze, democracy was eaten away by corrupt and unaccountable networks; under Saakashvili, swift and haughty policies have alienated large segments of the citizenry, including national minorities and the emerging ‘middle class’ he wants on his side. All three leaders failed to achieve a balance between the needs of de-stating – reducing the state’s role in the economy, creating greater institutional transparency, expanding self-government – and re-stating – regulating private interests, implementing laws, and strengthening national security. This takes time, but paradoxically, the dramatic paring of the state by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, fortified by Georgians’ own anti-state feelings, weakened constraints on the central government. The state must be effective to introduce radical reform, but in Georgia’s environment, where the rule of law is weak and personalism strong, the European tradition of state power, boosted by hasty reform from above, has bested the European tradition of civil rights.

Saakashvili’s administration illustrates the complicated tensions between democracy and state-building. Government policies designed to create a market paradise encouraged foreign investment, but in other ways hollowed out the meaning of democracy.8 The old casings of the imperial state, and the ingrained habits of citizens used to avoiding it, raised practical challenges to the practice of democracy in Georgia. Ambitious Western ‘democracy makers’, as Nicolas Guilhot calls them, added to the confusion by importing abstract models and concepts. But cloning democracy is not like cloning sheep.9 The major obstacles to democracy in Georgia are not hack-handed government repressions, or the conflict between civic and ethnic nationalism (a false dichotomy), or even external threats; rather it is the polarized and impoverished economy, the absence of organized social groups and social solidarities, and of trusted popular institutions. Georgian politicians have, as Ilia Roubanis puts it, ‘no strings attached [to their] power’, because they face no interest articulation or organized social constituencies from below.10 The post-Soviet environment under Gamsakhurdia – a lumpen classlessness with confusion and rage directed against the authorities, the intelligentsia, the West, and national minorities – has moderated, but not disappeared. Such rage threatens to return. The Saakashvili paradox – the reduction of the state combined with the augmentation of its power – has intensified the political elites’ de-legitimization and weakened their representative function. Neoliberal policies in Georgia hit the limits of reform and growth in 2007, and in the context of a global crisis that diminishes Western aid and attention, economic decline and social instability are likely elements in Georgia’s future.

A mechanical approach to institutional reform leads to poor outcomes. The well-intentioned introduction of the jury system in Georgia, for example, may not be a positive reform if jurors are subject to intimidation and pre-trial procedure remains weighted in the prosecution’s favor. The introduction of parent–teacher councils was a celebrated reform, but in the Georgian context (especially outside Tbilisi where patriarchal and deferential attitudes remain strong), it rapidly dwindled in confusion and conflict. ‘Reform’ is a useful word, but it is misused. There are more fundamental obstacles to personal liberty for Georgians than institutional ones, including joblessness, disease, crime, and corruption. These have dramatic consequences for democracy-living as well as democracy-building. The disastrous decline in the quality of life for most Georgians in the 1990s and the collapse of effective statehood underscored the problems of transition in post-Soviet states. Stephen Holmes suggests overzealous ‘de-statization’ added to the problem. Michael Mann goes further. Echoing Alexander Hamilton’s warnings about the ‘violence and turbulence of the democratic spirit’, he speculates on a ‘dark side of democracy’ that in certain contexts ‘leads to illiberal ethnic nations and weak states’.11

Thomas Carothers has contested the ‘transitional paradigm’, and its teleological assumptions about reform sequences leading to well-performing democracies. He suggests that many post-Soviet hybrids are stuck in a ‘gray zone’, where,

there is poor representation of citizens’ interests, low levels of political participation beyond voting, frequent abuse of the law by government officials, elections of uncertain legitimacy, very low levels of public confidence in state institutions, and persistently poor institutional performance by the state.12

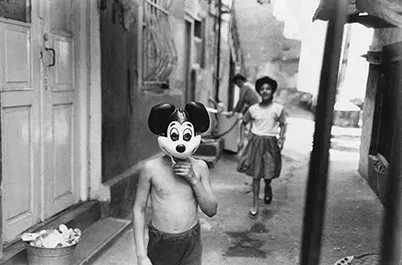

The West comes to Georgia. A Tbilisi street in the late 1990s.

The Rose Revolutionaries claim they have propelled the country out of this ‘gray zone’. But is Georgian politics today more participatory and more open than in the 1990s? The answer is not obvious. Public confidence in state institutions has increased since Shevardnadze’s departure, but the judiciary has low scores, along with local government and parliament. The Rose Revolution unjammed the machinery of ‘reform’, but did not convert impressive GDP growth and budget surpluses into mechanisms for overcoming poverty, de-industrialization, depleted agriculture, bankrupt social services, and territorial disintegration. A democratic model cannot be ‘dragged in by the ear’ (qurit motreuli), and grafted onto a new state when contesting nations (the Georgians, Abkhazians, and Ossetians) and contesting generations cannot agree upon its basic principles.13 Georgia’s limited experience of parliamentarianism, a powerful northern neighbor determined to destabilize the country, a persistent distrust of government, and a scattered civil society make democracy-building difficult in Georgia. Georgia is, by any legal definition, a democracy. But is it a virtuous democracy that legitimizes the state and works for its citizens?14

LEGACIES

Georgians have a proverb: ‘custom is stronger than faith’ (‘chveuloba rjulze umtkitsesia’). It reflects Georgians’ belief that the past is always trumps. The Soviet legacy – however misremembered, invented, or manipulated – is still embedded in Georgia’s present. It is an important part of why democratic institutions in Georgia are weak. The links between poor institutionalization and ‘charismatic’ leaders, weak parties and powerful presidents, frail civil society and secretive bureaucracies, environmental degradation and demographic stress, and the state’s failure to integrate national minorities are all related to the Soviet past.

The wiring of the Soviet state in Georgia was impressive: it gave Georgia a Supreme Soviet, its own council of ministers, a national budget, a trade union federation, a constitution, elections, local government, even its own foreign ministry. The republic had a state hymn (it began ‘Be glorious, my homeland…’), a flag, state emblem, and, of course, its own soccer teams (officially not ‘national’, they were more ‘national’ than most European teams are today). This national symbolism was not just a Potemkin-like façade. Even if Georgia’s political institutions followed the standard Soviet pattern, Georgian elites, especially outside Tbilisi, were able to administer their offices semi-independently. They benefited from what Valerie Bunce has called ‘subversive’ ethno-federal institutions, which ultimately undermined the unity of the Soviet state.15 Moscow, by the 1970s, was to a large degree an absentee landlord and Georgian institutions, though Soviet in form, were Georgian in content. Georgian ministries confirmed projects and budgets with Moscow, but implementation was a Georgian affair. Yet the ‘state’ the Georgians possessed was neither national, nor run by a modern civil service, and it was a weak and inefficient performer.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Soviet structures and psychology were a barrier to the democracy Georgians imagined they wanted. One of the most damaging Soviet bequests was a social and political chasm between elites and ‘subjects’. The Soviet state not only failed to penetrate society in Georgia, but ensured its irrelevance by relying on Georgian patronage systems, regional bosses, and networks to maintain its power. The Soviet state was never able to properly govern Georgia through institutions. Georgian dissidents in the 1970s, and NGOs, parliaments, and parties in the 1990s, failed to end this pattern of ‘us’ and ‘them’. Social dislocation and popular disillusion gener...