![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Pioneering Generation of

Caribbean Artists

When Rasheed Araeen included the sculpture of Ronald Moody in The Other Story: Afro-Asian artists in post-war Britain, Hayward Gallery, London, 1989, it was an opportunity for gallery audiences to acquaint themselves, or reacquaint themselves, with the work of an important Jamaican-born sculptor who had died about five years earlier. The Other Story brought together 11 of Moody’s key works, and collectively they formed a striking and impressive introduction to the exhibition. Whilst Moody had had a lifetime filled with making and exhibiting art, and undertaking other visual arts projects, it was only in the wake of his death that his work became more widely known, beyond the Caribbean art circles in which it had often been exhibited.

Moody was born in Jamaica in 1900 and was to spend well over half a century making art, right up until the time of his death in 1984. Though Jamaican by birth, Moody maintained something of an uneasy relationship with the country. There were no major exhibitions of his work in Jamaica during his lifetime, though he was awarded the prestigious Gold Musgrave medal by the Institute of Jamaica in the late 1970s. The first substantial exhibition of Moody’s work at the National Gallery of Jamaica took place in 2000, some 16 years after his death.

Moody was a sculptor who came to his practice after being inspired by visits to the British Museum, where he was particularly drawn to the galleries of Egyptian and Asian art. From his earliest work through to his later practice, Moody’s sculptures reflected his interest in ancient and world ideas of metaphysics (the branch of philosophy that deals with the first principles of things, including abstract concepts such as being, knowing, substance, cause, identity, time, and space.) In contrast to this distinctive work, Moody produced a number of portraits, in a somewhat more conventional, though nevertheless striking, vein. These included a bust, made in 1946, of his brother Harold Moody. Some years previously, in the early 1930s, Harold Moody had been instrumental in founding, in London, the League of Coloured Peoples, which had the aim of racial equality for all peoples throughout the world, though the league’s principal focus of activity was the racial situation in Britain itself. Another very important bust produced by Ronald Moody was his rendering of Paul Robeson, the African-American singer, actor of stage and screen, and civil rights campaigner, in copper resin, in 1968.

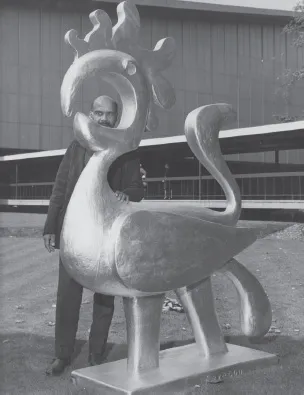

3. Bird that Never Was arrives in Kensington (21 August 1964), press photograph with the following note:

Placed in position on the lawn of the Commonwealth Institute in High Street, Kensington, today, was a 7ft 10in tall, 5 cwt cast aluminium sculpture of a mythical “SAVACOU” bird, which was designed by Jamaican sculptor RONALD MOODY. The “SAVACOU” which existed only in Caribbean mythology, will remain there on view to the public for about a month before going to Jamaica where it will be placed in front of the Epidemiological Research Unit of the University of the West Indies, to whom it was presented by their director, and the director of a smaller unit in South Wales.

In looking at his sculpture, particularly his dramatic faces, heads, and figures, his work has the appearance not so much of racialised imagery (what we might term the Black image, or the Black form); instead, it presents itself to us as a compelling amalgamation of the breadth of humanity. It is in work such as Johanaan that we see most clearly the artist’s embrace of the transcendental and the metaphysical. Veerle Poupeye noted that ‘In the 1960s Moody became more actively interested in his Caribbean background. His best-known work of the period, Savacou (1964) represents a stylized, emblematic parrot figure inspired by the mythical bird deity of the Carib Indians.’1 The work exists in both its finished form (as a commission for the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica) as well as in maquette form. The finished work, made of aluminium, is a dramatic and distinctive feature of the campus. A photograph of the work is reproduced in this book.

In the years following The Other Story, Moody’s niece, Cynthia Moody, worked tirelessly to preserve, safeguard and advance his legacy. A hugely significant landmark of this process was the acquisition by the Tate Gallery, in 1992, of the magnificent and imposing figure of Johanaan (sometimes known as John the Baptist). Unfortunately, Moody’s sculpture has yet to be the subject of a major monograph, though a number of texts on his life and practice have been published. Chief amongst them perhaps is Cynthia Moody’s own Ronald Moody: A man true to his Vision, which appeared in Third Text;2 and Guy Brett’s substantial feature on Ronald Moody in the magazine Tate International Arts and Culture.3 The Brett article, ‘A Reputation Restored’, was introduced as follows: ‘Self-taught wood-carver Ronald Moody, a former dentist born in Jamaica, is revealed as one of Britain’s most remarkable Modernist sculptors in a new display at Tate Britain.’4

An invaluable appraisal of Moody and his work appeared in British magazine The Studio, in the January 1950 issue of the magazine.5 The writer, Marie Seton, had the measure of Moody when, early on in the text, she expressed the view that the sculptor’s work, ‘is concerned with man as an evolving type, is unique, haunting and far from easy to label.’ The wide-ranging text recalled moments of high drama in Moody’s life, particularly his escape, with his wife, from Nazi-occupied France. He had earlier moved to Paris, where his first one-man exhibition ‘took place towards the end of 1937 at the Galerie Billiet-Vorms.’ Recounting Moody’s flight, Seton wrote:

Then the German juggernaut approached Paris and many of Moody’s most beautiful works were dispersed across occupied France. Moody and his wife escaped from Paris with the stream of refugees and finally reached Marseilles on foot. For months the existence of a refugee kept him inactive. This terrible period has left its mark upon his later work, accomplished when at last he escaped to England (by the daring act of walking across the Pyrenees into Spain and crossing that country with the help of the ‘underground’ to Gibraltar.’6

Clearly a great admirer of Moody’s work, Seton noted, ‘With each work he has captured a greater degree of sensitivity within the human spirit and achieved a greater and more subtle feeling of spiritual unity.’7

Moody’s work was included in the exhibition Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance, which toured to galleries in the UK and the US in 1997 and 1998. Within the exhibition’s catalogue there is a fascinating full-page reproduction of a gallery installation view of Children looking up at Ronald C. Moody’s Midonz (Goddess of Transmutation), taken in 1939. Within the credit, neither the United States’ gallery nor the exhibition itself are identified. The exhibition was very likely to have been one sponsored by the Harmon Foundation, which was particularly active in exhibiting work by Negro artists during the 1930s.

Guyana (formerly British Guiana), a relatively small country nestled between Venezuela, Brazil and Surinam, produced several pioneering Caribbean artists who made their way to Britain during the mid twentieth century. These artists included Denis Williams, born in 1923, Aubrey Williams (1926), Donald Locke (1930) and Frank Bowling (1936). In years to come, another Guyana-born artist, Ingrid Pollard, born in 1953, would also figure prominently in narratives of Black artists in British art. Bowling first came to London at the age of 14, to complete his schooling. He was first a poet, eventually turning to painting in his late teens. After periods of study at art colleges in London, his career as a painter began in earnest with solo exhibitions in London in the early 60s. Bowling has come to be universally known and widely respected for his abstract paintings, ranging from large expansive affairs rich with colour and texture, through to smaller, much more compact works. He came to abstract art via figurative painting, at the beginning of the 1970s. Before that time, his art of the late 50s and 60s was figurative and resonated with distinct social and political narratives. Bowling himself cited the death of Patrice Lumumba (in 1961) as being one of his themes during this period.8

Whilst Bowling was born in Bartica, a tip of land by the Essequibo river, Williams was born in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital. After settling in London in his late twenties, he enrolled at St Martin’s School of Art and soon established a career as a prolific and on occasions widely exhibited artist. An active member of the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM), Williams came to be closely associated with the presence of Caribbean art/artists in London and his work was featured in a very significant number of Caribbean art exhibitions. One critic sought to explore the commonalities shared by Bowling and Williams.

On the face of it, Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling have little in common apart from being modern artists from Guyana who chose to work in different modes of abstraction. Abstract expressionism was predominant when Williams enrolled at St Martin’s School of Art in London in the mid 1950s, whereas Bowling’s career began after he graduated from the Royal College of Art in 1962 when Pop Art was the rising paradigm of the mid 1960s. While such generational differences account for their dissimilarities as abstract artists, it could be observed, however, that Williams and Bowling shared a modernist commitment to the practice of painting as an intellectual activity that demanded continuous reflection on the ideas, sources and materials of their work.9

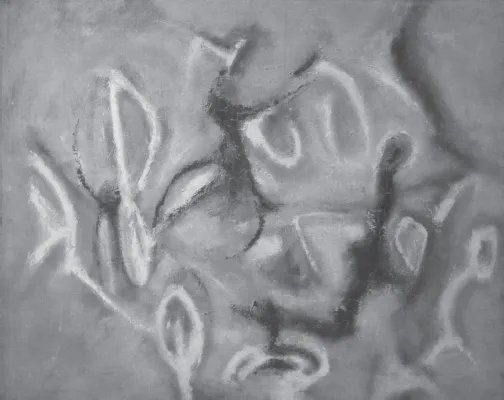

4. Aubrey Williams, Arawak (1959).

In a number of ways, the environment that Black immigrant artists found in the London art world of the 1950s and early 1960s was wholly conducive to their ambitions as artists and their keenness to contribute to the exciting culture of Modernism, which they regarded as having pronounced international dimensions that created a tangible commonality amongst artists. This moment ultimately proved to be something of a fleeting one, though whilst it lasted artists such as Williams and Indian artist Francis Newton Souza were able to exhibit regularly. Kobena Mercer described London’s environment of what he called ‘a post-colonial internationalism’:

Williams also participated in what could be called a post-colonial internationalism that played a significant role in the independent gallery sector. The New Visions Group, which hosted three solo exhibitions by Williams between 1958 and 1960, had been formed by South African artist Denis Bowen in 1951. Dedicated to non-figurative art, the group operated as a non-profit artists’-run organisation whose exhibition policy for the Marble Arch gallery it opened in 1956 promoted abstract artists from Commonwealth countries alongside tachisme, constructivism and kinetic art from various European contexts. Gallery One, set up by Victor Musgrave in 1953, hosted five exhibitions by the Bombay artist Francis Newton Souza, as well as exhibiting avant-garde Europeans such as Yves Klein and Henri Michaux for the first time in Britain. Such openness towards non-western artists was part and parcel of a broader generational shift. Artists such as Souza, Anwar Shemza and Avinash Chandra, who had already achieved professional recognition in India and Pakistan, featured in Gallery One’s widely acclaimed Seven Painters in Europe (1958) exhibition.10

Both Bowling and Williams secured significant exhibition opportunities for themselves, as young painters in London in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In this endeavour, the Grabowski Gallery (which one art historian succinctly described as having a ‘global outlook’)11 was of huge importance. Grabowski Gallery, London, operated between 1959 and 1975. It was the art gallery of a Polish pharmacist, located at 84 Sloane Avenue, Chelsea, London SW3. In 1960, Williams exhibited there alongside Denis Bowen, Max Chapman, and Anthony Underhill, in an exhibition titled Continuum. In 1962, it was the venue for Image in Revolt, two concurrent solo exhibitions of paintings by Derek Boshier and Frank Bowling. Both artists were at the time in their early to mid twenties. Shortly thereafter, Grabowski Gallery again exhibited the work of Bowling in a group show that also included the work of two other artists from Commonwealth countries: William Thomson (Canada) and Neil Stocker (Australia). Williams also had a solo exhibition at Grabowski Gallery, in January of 1963. The extent to which Bowen and Williams worked together during the late 1950 and early 1960s was indicated in an addendum that Bowen wrote for an obituary on Aubrey Williams, published in the Guardian newspaper shortly after the artist died in 1990: ‘Aubrey Williams was one of the most outstanding and individual of the artists who exhibited at the New Vision Centre Gallery in London which I directed from 1956 to 1966.’12

These early career successes of Bowling and Williams were followed by other periods of notable accomplishments, though in the case of Williams, his most substantial exhibitions were very much posthumous endeavours, the artist himself dying in 1990. But for pretty much all of the rest of the twentieth century, these artists’ (and indeed other Black artists) periods of relative success very much alternated with periods during which they struggled to maintain professional visibility. To a great extent, this cycle of periods of relative visibility being punctuated by longer periods of invisibility was something that has to differing degrees characterised the history of Black-British artists from the mid twentieth century onwards. In some instances, as mentioned earlier, certain artists’ most successful episodes of visibility have been posthumous. Throughout the period covered by this book, the visibility of Black-British artists – both individual visibility and group visibility – has been subject to a variety of pressures, factors and on occasion, initiatives taken by artists themselves. Again, some of these initiatives have been taken at an individual level and some have come about as a result of group or institutional activity.

An indication of Bowling’s determination to succeed as an artist can be ascertained in the opening remarks of a review of the aforementioned exhibition he shared with Derek Boshier, Image in Revolt, at Grabowski Gallery in 1962:13

[Bowling] is twenty-seven years old and comes from British Guiana which he left about eleven years ago. Born to be an artist, he has felt a certainty of his own destiny that will not be denied, come hell or high water.14

Despite early career successes, Bowling found himself on a trajectory somewhat different from that of the white friends and colleagues with whom he had studied and enjoyed early exhibition opportunities. In one of his essays for The Other Story catalogue, Rasheed Araeen took up the dispiriting tale.

[Bowling] was on his way to a successful career when things began to go wrong. Although he considered himself part of that Royal College group (Hockney, Boshier, Kitaj, Phillips) which represented the emergence of ‘new figuration’ in Britain, [Bowling] found that he was being left out of group exhibitions, on the basis that his work was different...