![]()

Section I

BEUYS AND HIS ‘CHALLENGERS’

![]()

| 1. | BREAKING THE SILENCE |

| | Joseph Beuys on his ‘Challenger’, |

| | Marcel Duchamp* |

| | ANTJE VON GRAEVENITZ |

IN LECTURES OR IN recorded conversations with others, Joseph Beuys did not often quote other artists or draw parallels with them in regard to his own work. Those he did mention included Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Dürer, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Wilhelm von Gloeden and Marcel Duchamp. One should not forget Jackson Pollock, whom he constantly brought up when asked which artists he particularly valued, without further explanation as to why the American painter, known for all-over compositions and drip paintings, played an exceptional role for him.1 Among those mentioned, Duchamp occupies a special place; Beuys made frequent and critical comments about him. Thus one might conclude that he wished to contrast himself with Duchamp, since Duchamp was regarded as responsible for every new direction in art from the 1960s until the 1980s, such as Fluxus, Pop Art and conceptual art. Duchamp was generally honoured as the father or inventor of contemporary art.

At the time, therefore, it was necessary for a young artist to protest such discouragement. If one listens carefully to the discussions with Beuys that are passed down in recordings, reads the interviews and views his works perceptively, then one can no longer describe his critique as merely motivated by competition or small-mindedness. Duchamp mattered much more to him than that.2

In ‘Entrance to a Living Organism’ (‘Eintritt in ein Lebenswesen’), a lecture on 6 August 1977 at Documenta in Kassel, Beuys spoke to what was generally a lay audience in simple, fairly disparaging words about Duchamp. To begin with, he briefly outlined his own development as well as his search for possibilities to become active in artistic practice in the face of the ‘annihilation of mankind’ and the ‘destruction of the earth’. He then continued: ‘I have also noted in one work of Marcel Duchamp, which is very complex and experimental in nature, that one must pose the question quite differently. That is the question of the critical situation of art itself.’ It is not enough, Beuys said, that one turns directly to a picture. One has to allow new experiments and subsequently expand the concepts for the work. And, while Duchamp experimented, he did not draw conclusions from his methods. ‘Duchamp was a slacker who completed beautiful and interesting experiments as shocks to the bourgeoisie, and those were done brilliantly in the aesthetic typology of the time’ but, for all that, he did not develop a category of thought for it. Duchamp signed an industrially produced urinal with a pseudonym and displayed it in an exhibition so that it would be perceived as art, although it wasn’t produced by him but rather by many workers. He did not draw conclusions from this situation. ‘If it is possible to transfer the results of human work from the world of the division of labour into the museum, he should also have said, as I concluded: therefore everyone is an artist,’ and Beuys laughed loudly.3

In 1985, he spoke again about Duchamp’s urinal, this time with more deference, in an English-language discussion with William Furlong in connection with Beuys’ work Plight in the Anthony D’Offay Gallery in London; he further contrasted his ‘expanded concept of art’ to Duchamp:

So he did not enhance all the work and all the labour to a new understanding of art as necessity … to start everything in order to understand all aspects of human kinds of labour from his view. This would have been of great importance, because since then it could have already become a kind of discussion about existing ideology in society, the capitalistic system and the communistic system: the germ in the right directions practised by Marcel Duchamp. But then he distanced himself from further reflection. So he did not understand his own work completely.4

Had he drawn conclusions from his actions instead of wanting to shock the bourgeoisie, as was befitting a dadaist at the time, Duchamp would have transformed art. Beuys continued:

So in being very modest, I could say: my interest was to make another interpretation of Marcel Duchamp. I tried to fill this most important gap in his work and make a statement, ‘the silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated’. You know, after he stopped working, playing chess, he did not speak any more about art, he was completely silent; he cultivated this kind of silence in a very old-fashioned form. He wanted to become a heroin-silence or in doing nothing or in resigning from art … So I principally tried to push this beyond the threshold of modern art into an era of anthropological art, as a beginning in all fields of discussion … not only of minor problems.5

Beuys’ declaration is astonishing for two reasons: while on the one hand he saw the seeds of the ‘expanded notion of art’ in Duchamp’s work, on the other he established a view of twentieth-century art history that credited only two artists with the development of art and then created a rift between them. He regarded Duchamp as the terminator of modern art but himself as the initiator of an anthropological art, as he called it.

Already in June of 1984, he had put forward a similar explanation in a discussion published in French and Italian and had similarly defined, by means of his expansion of Duchamp’s abandoned work, the ‘anthropological material’ that remained to be developed: ‘The primary anthropological material of mankind is thought, emotion and will.’6 He mentioned these three concepts, in reverse order, as constituting the stages of his theory of sculpture (‘Plastik’). He had formulated this for Dieter Koepplin and established them as parallels to the principles of chaos/will, movement/perception, and thought/action.7 His goal was to encourage the free and active mental creativity of the viewer. To that end, his art should only have a demonstrative and evocative character.

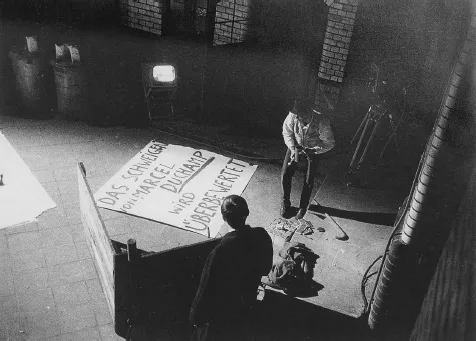

On 11 December 1964, the silence of Duchamp gave Beuys the opportunity to stage a programmatic performance (‘action’) with the title The Silence of Marcel Duchamp Is Overrated (Fig. 1.1). It took place in the studios of the ZDF North Rhine-Westphalia television station and was broadcast as part of the series The Potter’s Wheel (Die Drehscheibe) under the name ‘Fluxus Group’. The nonsensical silence of art in the face of pressing questions about the future was made doubly apparent through the medium of the broadcast. As a former radio operator in the air force, Beuys knew about the significance of transmission and about how to make use of the broadcast in a meaningful way for his ‘anthropological art’.8 Uwe M. Schneede covered the action itself in his book Joseph Beuys Die Aktionen; 9 Schneede claims that Beuys was apparently inspired by Robert Lebel’s Duchamp monograph.10 Felt, fat (margarine cartons), ringing chimes, the colour ‘Braunkreuz’ (brown cross, a cross/bandage meant as a healing sign), the walking stick and chocolate (is there a connection to Duchamp’s chocolate grinder in the Large Glass?) were Beuys’ materials. As in all of Beuys’ works, their use in the action is meaningful; the materials themselves indicate principles of nature such as chaos, warmth and energy. They also represent anthropological tasks for mankind: transmission (the chimes, the iron-based colour), preservation, protection and direction (the staff), as well as the ‘gift of love’, chocolate. The diversity of these substances and the strange carryings-on should be interpreted by their displacements of meaning to existentially human qualities. On the one hand, the shapes are there to be seen; on the other, the material mediates theoretical principles, as in an epiphany. Only an epiphany can bring about recognition in the viewer. For that reason, Beuys’ works appear as means of transportation, as vehicles for the spirit.

1.1. Joseph Beuys, The Silence of Marcel Duchamp Is Overrated, 1964; © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Diversity, displacement of meaning and interpretation based on analogy were already important in Duchamp’s work.11 Beuys must have particularly enjoyed that Duchamp also began with an emblem appropriate to the vehicular quality of art, his bicycle wheel mounted on top of a kitchen stool of 1913. At the time, Duchamp designated the work ‘readymade’, in which, according to Zaunschirm, a code is hidden for an erotic emblem of art: ‘willing girl’.12 Duchamp himself explained that he kept it in his studio for amusement and as a vehicle for thoughts about art.13 Fifty years later, on 1 July 1966, he declared that he had not thought of the artwork in the sense of an object for exhibition. Beuys liked to refer to his art as ‘warmth ferry’, and repeatedly made use of the vehicle as an emblem for the creative flow of thought. This is not only true of the Transsibirische Eisenbahn (Trans-Siberian Railway), but also of the Urschlitten (Sled) multiple, and of the VW-transport of The Pack (Das Rudel).14 He had already completed a work consisting of a photograph of a bicycle taped onto a sheet of paper that originated from the action of the same title, The Silence of Marcel Duchamp Is Overrated.15 In contrast to Duchamp, Beuys later selected an entire functioning bicycle, which was apparently dedicated to Duchamp, for the exhibition Quartetto in a Venetian church that adjoined the Biennale exhibition site.16 The work took up a considerable part of the church’s space and consisted of fifteen blackboards, some covered with white and coloured chalk drawings. The gallerist Konrad Fischer had installed them in a line across the floor behind the upright bicycle. The piece is characterized by the question posed in its title, Is It about a Bicycle?, with an addition in the catalogue, From Vehicle-Art.17 Otherwise, Beuys did not pose questions in his titles; statements were more suitable to him as in, for example, his remarkable postcard-slogan ‘Ich denke sowieso mit dem Knie’ (‘Anyhow I think with the knee’).18

The Irish art critic Dorothy Walker has offered a possible explanation for the title of Is It about a Bicycle? During one of Beuys’ stays in Dublin she introduced him to the book The Third Policeman by the writer Flann O’Brien. This book is an absurd, philosophical work that has to do with a wild search for a missing ‘black box’; a confused policeman poses the completely misguided question, ‘Is it about a bicycle?’19 The answer is ‘no!’ – always an easier answer than ‘yes’. An observant reader may know that, earlier in the book, the italicized command, ‘Use Your Imagination’, was stressed.20 This could in fact have appealed to Beuys, since he always valued the powers of human intuition and imagination. His student Johannes Stüttgen, who was also responsible for the picture- and text-drawings on the fifteen blackboards, does not recall that Beuys ever mentioned O’Brien’s name. The title, he said, was decided upon during a drive they had made from Goslar to Düsseldorf. Perhaps Beuys remembered O’Brien on this occasion?

While Bernard Lamarche-Vadel reproduced all fifteen boards in colour, his book never mentioned the fact that the work resulted from an extensive collaboration between teacher and student – incidentally a singular case in Beuys’ work – nor did Lamarche-Vadel investigate the relationship with Duchamp’s work. Therefore, the factual circumstances of The Third Policeman need to be commented upon here.21

The work was created in instalments. Since Beuys had already organized lectures or discussions in previous Documenta exhibitions, he wished to be represented only with his action 7,000 Oaks at the 1982 Documenta. Therefore he left it to his student, Johannes Stüttgen, to convene fifteen weekly seminars on the work of his teacher in the (Apollo) tent whi...