![]()

Chapter 1

Bakhtinian aesthetics

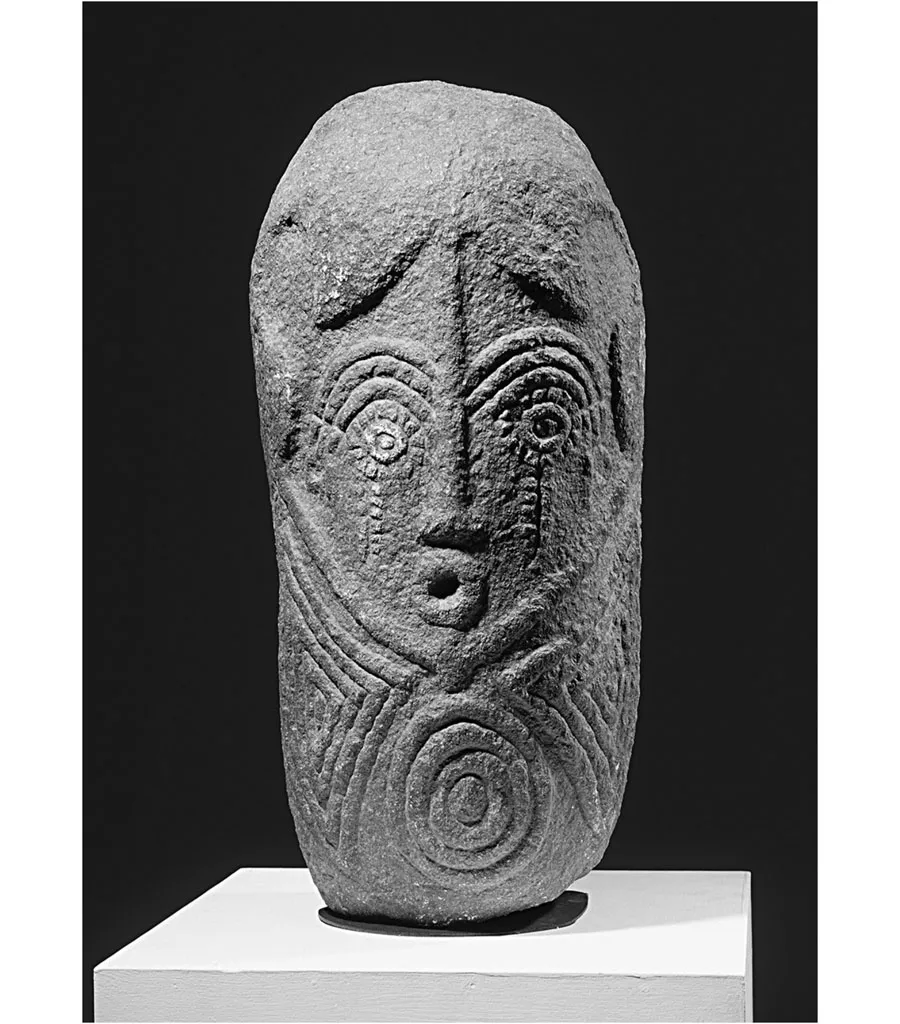

I did not grow up near major national or international museums; my love of museums began during my first solitary trip to New York City as a young adult. Years later I lived close to the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, Massachusetts, and I would often stop by to see the latest exhibitions and visit a favourite gallery or a particular work of art. During one of my infrequent visits to the MFA after moving across the country, I was strolling through newly installed galleries of African art. Suddenly I was riveted by a basalt sculpture with a distinctly human face (Figure 1). I stopped and stared at it, and the stone seemed to stare back. I made multiple drawings in my journal, which inspired subsequent art of my own. This experience was one of a few such life-changing events that involved looking at art.1

This particular stone monolith has an overall ovoid shape, with a face carved in low relief on its front. The face consists of a long nose, deeply incised round mouth and small eyes with multiple brow lines. Cuts into the face appeared to be tears when I first scrutinised it, but probably allude to facial tattoos, painting or scarification. The face is framed by raised lines and has a smooth, domed top. Spirals and angular lines are carved below. This stone, called atal or akwanshi, was carved between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and comes from the Cross River region of Central Africa. Made of basalt, it is approximately 29 inches tall. Although sculpture made of such hard stone is rare in sub-Saharan Africa, about 300 similar works have been documented from the forested region of the mid-Cross River in Nigeria. The Ejagham peoples who live in this region call them akwanshi (dead person in the ground); neighbouring groups refer to these monoliths as atal (the stone). Perhaps intended to memorialise the dead, atal were carved from volcanic boulders by grinding or pecking with stone or metal tools to create a human face and simplified body.

1. Carved stone (Atal or Akwanshi), Nigeria, eighteenth-nineteenth century, Photograph © 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

These stones are deemed significant enough to be mentioned in textbooks and they attract attention among tourists, but it is hard to find reliable information about why and how they were created. As Philip Allison described in one of the only extant publications on these stones, it has been difficult to collect any coherent oral knowledge about their history. Traditions related to the stones remain vague, and the stones are generally described by residents of the area as having been carved ‘a very long time ago by the forefathers of the present occupiers of the land and to commemorate the ancestors of the tribe or village’ (1968: 35). Further difficulty tracing their history is related to the fact that many atal have been moved from their original locations, broken and ‘repurposed’ – used in more recent building construction. However, the most pertinent point is my encounter with the MFA atal, not the anthropological and art historical details that have been lost.

In this chapter I explore Bakhtin’s aesthetics in order to provide a philosophical grounding for the book. Of particular focus are his ideas regarding ‘art for life’s sake’ and ‘theoretism’; I consider both of these concepts foundational to his oeuvre. While my discussion of aesthetics as a form of theoretism is technical, it is intended to offer a summary of Bakhtin’s philosophical interests. Yet here, at the beginning of the chapter, I also want to raise complex questions about whose aesthetics we rely on and use. The tradition of placing atal in the ground evolved in Central Africa among communities with no access to these European traditions. Are the aesthetic categories derived from European philosophy and art history adequate for engaging and understanding the art of cultures outside the European West? If so, how are they useful and what are their limitations? If not, how can one gain a thorough grounding in cultural theories that may be unfamiliar? I will return to these questions at the end of the chapter after discussing African aesthetics. I believe it is imperative for both art historians and artists to familiarise ourselves with art outside of the Western canon, and to ask if and how the theories we use are relevant in other contexts.

Art for life’s sake

More than two decades ago I was drawn to Bakhtin’s writing when I read ‘Art and Answerability’ in Russian, an essay he wrote in 1919. I laboured over the translation of various words, and my curiosity was piqued. I had been interested in the religious and moral overtones of the nineteenth-century debate about art for art’s sake versus art for life’s sake. In his short two-page essay, written at the young age of 24, Bakhtin clearly located himself in the art for life’s sake camp, and I recognised him immediately as a kindred spirit. Art and life, he stated, should answer each other. Without recognition of life, art would be mere artifice; without the energy of art, life would be impoverished. One of the most significant points of connection between art and life is the human act or deed. Even if we do not know the artist’s name, a work of art such as the atal is an example of the artist’s action in the world. Carved and placed in a forest setting, the atal expresses both individual creativity and community values – precisely the intersection of art and life that Bakhtin valued.

Philosophically based in the writings of Kant, Schiller, Goethe, Schelling and Friedrich Schlegel, the idea of art for art’s sake had adherents in France, England and Germany, especially during the nineteenth century.2 Among its primary tenets were the following interrelated ideas. First, art has its own distinctive sphere in which the artist is sovereign. Second, the artist’s freedom is essential because the artist should be committed only to personal vision and not to his or her culture, school or a given formal structure. Third, the so-called ‘true’ artist is concerned only with aesthetic perfection and not with the personal or social effects of the work of art. In other words, the highest goal of life should be aesthetic creation rather than moral development or religious values. Fourth, aesthetic perfection is achieved through the expression of form, where ‘expression’ is understood to mean that an artist expresses inner vision rather than outer appearance. Fifth, creative imagination should predominate over cognitive or affective processes of thought and reflection. These ideas were expressed in literature and the visual arts in a variety of ways, but for Bakhtin art for art’s sake constituted a fundamental crisis, an attempt by writers and artists simply to try to surpass the art of the past without considering their own moral responsibility. In contrast, Bakhtin followed nineteenth-century aestheticians such as Jean-Marie Guyau, who were convinced that art must be deeply connected to life (1947).

At its foundation, Bakhtinian aesthetics is profoundly moral and religious. In fact, Bakhtin’s early aesthetic essays derived many of their terms from theology (Pechey 2007: 153). For example, in notes taken by L.V. Pumpiansky during Bakhtin’s lectures of 1924–25, Bakhtin reputedly said that aesthetics is similar to religion inasmuch as both help to transfigure life (2001: 207–8). He discussed how ‘grounded peace’ is foundational for both religious experience and aesthetic activity. Grounded peace is an odd term, but it is used here to mean a state of rest, tranquility and peace of mind. This interpenetration of the religious and aesthetic is further expressed throughout Bakhtin’s writing with themes such as love, grace, the urge toward confession, responsive conscience, reverence, silence, freedom from fear and a sense of plenitude. Yet even if Bakhtin’s political and cultural context had allowed it, he would not have been inclined to ‘preach a religious platform’, as Caryl Emerson so astutely observed (in Felch and Contino 2001: 177). He was, by temperament, neither didactic nor proselytising.

Theories and theoretism

Mikhail Bakhtin’s understanding of European philosophical aesthetics evolved in relation to his historical situation, which I will discuss in greater detail in Chapter 6. But interpretations of historical processes and events are not the only part of his context. His early essays and later books and essays are filled with both tacit and overt philosophical references, many of which are obscure for the contemporary reader. Many statements remain incomprehensible unless interpreted in relation to Bakhtin’s partners in intellectual conversation, especially Kantian and Neo-Kantian philosophers.

Since the 1730s when Alexander Baumgarten coined the term, ‘aesthetics’ has remained ambiguous. For Baumgarten and for Kant, who expanded on his ideas, aesthetics had to do with sensory knowledge or sensory cognition, which included but was not limited to the problem of beauty. In a broad sense Bakhtin’s understanding of aesthetics fits into such a definition. He was concerned with how humans give form to their experience – how we perceive an object, text or another person, and how we shape that perception into a synthesised whole. But rather than focusing on beauty as in traditional aesthetics, Bakhtin developed a unique vocabulary for describing the process by which we literally ‘author’ one another, as well as artifacts such as works of art and literary texts, with concepts that I discuss in detail in the next chapter.

Bakhtin actively refuted Kantian aesthetics from two directions. First he challenged ‘impressive’ theorists such as Konrad Fiedler, Adolf Hildebrand, Eduard Hanslick and Alois Riegl, who, in his view, centred too heavily on the creating consciousness and the artist’s interaction with the material. In his essay ‘Artist and Hero in Aesthetic Activity’, Bakhtin twice mentions Riegl as one of those historians for whom ‘the artist’s act of creation is conceived as a one-sided act confronted not by another subiectum [subject], but only by an object, only by material to be worked. Form is deduced from the peculiarities of the material – visual, auditory, etc.’ (1990: 92). Because Riegl was a European art historian whose influence helped to shape the modern discipline of art history, a brief discussion of his ideas is relevant here. Had he known more about Riegl, Bakhtin might have viewed him as a congenial thinker.

Riegl attacked many traditional art historical methods, including factual history, iconographical study that stressed subject matter, biographical criticism that focused on the artist, mechanistic explanations of style, aesthetics severed from history and hierarchical distinctions between the arts (Zerner 1976: 179). That Bakhtin would have challenged Riegl’s ideas is understandable, especially given Riegl’s articulation of the importance of Kunstwollen, variously translated as ‘artistic intention’, ‘formative will’ or ‘stylistic intent’. With the concept of Kunstwollen, Riegl was searching for an adequate way to describe the continuous development of visual form – that is, how styles are transformed from culture to culture and from one historical period to the next. Riegl insisted that all stages and expressions of art are of equal value, though the artist’s intention would be expressed in different ways. Therefore he considered judgements about both progress and decline to be problematic. In contrast to the mechanistic models of other art historians, Riegl interpreted artistic creativity in a much more complex way, emphasising a view of the artist as an individual seeking to resolve unique artistic problems (Pächt 1963: 191). Nevertheless, he tended to negate the importance of the individual in favour of larger creative forces in history. In this he followed the trend of late nineteenth-century thought, which valorised evolutionary ideas over individual innovation (Holly 1984: 78–79). Yet Riegl’s formalism was modified by his interest in the acting agent, the creator in artistic activity. Bakhtin’s criticism that Riegl looked only at the object and material seems too reductionist. Although Riegl did not use the language of consciousness, self and other that Bakhtin preferred, he certainly did attempt to think inclusively about the relationship of artist, artwork and context.

Bakhtin’s second challenge to modern aesthetic theories turned in another direction. In addition to criticising impressive aesthetics, he was convinced that ‘expressive’ theories were limited because they were based on the idea that art is primarily an expression of feelings and the inner self. Taking the human being as the primary subject and object of inquiry, expressive aesthetics is decidedly anthropocentric. Everything, even line and colour, is given human attributes. Within expressive aesthetics the goal of aesthetic perception and the aesthetic act is to empathise and to experience the object as if from within, such that the contemplator and the object literally coincide. There is no juxtaposition of an ‘I’ and an ‘other’, which in Bakhtin’s view was essential to the aesthetic process.

His critique of expressive aesthetics was based on three main points. First, empathy occurs in all aspects of life, not just in aesthetic experience. How might my empathetic response to the tears I perceived on the face of the atal be different from my empathetic response to my friend’s divorce? ‘Expressive’ philosophers such as Theodor Lipps and Hermann Cohen do not describe how aesthetic coexperiencing and empathy differ from empathy more generally; consequently, Bakhtin believed their theories had limited applicability. Second, expressive aesthetics cannot adequately account for the entirety of a work of art because it focuses on the artist’s or viewer’s feelings. What of the geographical context that determines available materials, or the political context that informs a work of art? Expressive aesthetics would not get us very far in interpreting the atal. Third, it cannot provide the basis for understanding and interpreting form because it fails to see the complex processes through which particular cultural and individual forms evolve. Bakhtin placed a diverse group of philosophers – Lipps, Cohen, Robert Vischer, Johannes Volkelt, Wilhelm Wundt, Karl Groos, Konrad Lange, Arthur Schopenhauer and Henri Bergson – in this category of expressive aesthetics and tried to develop an alternative and more adequate approach.3

In contrast to both impressive and expressive theories, Bakhtin described aesthetic activity as a three-part process. The first moment is projecting the self: to experience, see and know what another person experiences by putting oneself in the other’s place. This moment is similar to the Neo-Kantian notion of empathy. My own immediate response to the atal in its MFA setting – feelings of compassion and curiosity about the ‘tears’ that I perceived – was understandable, especially given that a beloved friend was very ill and dying at that time. Bakhtin’s second moment of aesthetic activity properly begins only when one returns to one’s singular place, outside of the other person or object. This occurred for me when I began to seek more information about the cultural and artistic traditions of the atal, and a few months later initiated a marble sculpture that was inspired by the atal’s form.

The third moment is less relevant to my experience of the atal. In Bakhtin’s model, the viewer can ‘fill in’ the other’s horizon, ‘enframe him, create a consummating, that is finalising, environment for him out of this surplus of my own seeing, knowing, desiring, and feeling’ (1990: 25). In this statement Bakhtin seems to say that all power resides in the self. Such power to ‘enframe’ is dangerously close to the power to control and imprison. Certainly, with his benign view of the universe, imprisonment would have been far from Bakhtin’s mind, but the implications of such language cannot escape the notice of a twenty-first-century reader. The importance of his model is that Bakhtin brings us back to the aesthetics of the creative process itself – back to the activity of the artist who creates.

Still, Bakhtin never explicitly defined aesthetics. Unlike both Kantians and Neo-Kantians, Bakhtin shunned orderly systematic thought, preferring instead to muse and work out ideas by following the circuitous and often fragmentary meanderings of imagination. His early essays, especially ‘The Problem of Content, Material, and Form in Verbal Art’, contain his most sustained treatment of philosophical aesthetics (Bakhtin 1990). Following Kant, Bakhtin treated the aesthetic as a s...