![]()

Chapter 1

The image

Introduction

The Australian art scene was sent into a spin when police raided an exhibition of photographs by internationally renowned artist Bill Henson. The offending artworks – seized as suspected child pornography – depict nude, underage boys and girls. The children in question are understood to have consented to model for the series with the approval of their parents (Wilson and Trad 2008). For those who are unfamiliar with Henson’s photographs, they often depict teens in various unclothed and semi-naked poses amidst gloomy settings. Up until now, what has made his works unforgettable is not so much his subject matter but his use of chiaroscuro – contrasting light and dark elements – to generate a dual effect of beauty and unease. For more than 25 years Henson has been exploring the darker aspects of the transition to adulthood, rendering the not-quite-childlike but not-yet-adult subject in a series of large-scale, haunting studies. At the 49th Venice Biennale his depictions of pubescent, sometimes androgynous, bodies showed to much critical acclaim but no discernible public outcry. Before this incident no one seems to have complained about his artworks, which are held by major galleries in Australia, as well as overseas.

After what happened at the Sydney gallery in May 2008, where more than 20 artworks were confiscated, Henson’s pictures were denounced by the Prime Minister of Australia, among others. To be sure, Henson isn’t the first artist to be accused of sexualising children and young adults. American photographers Sally Mann and Tierney Gearon courted controversy by exhibiting nude pictures of their own offspring throughout the eighties, nineties and beyond. Jock Sturges and David Hamilton’s photographs depicting unclothed adolescent females have provoked accusations of child pornography. In the nationwide media debate that ensued from the Henson affair, a number of commentators pointed out that representations of naked children have long been a part of the Western art canon. Sharing this view is noted feminist Germaine Greer, who remarked:

Renaissance paintings are festooned with the naked bodies of babies displayed in the most fetching of poses; small naked boys sit splay-legged on the steps of temples and astride beams and boughs. The public that saw them included pederasts and pedophiles, but nobody deemed that a reason for not showing them. The Christ Child sat astride his mother’s knee displaying his perfect genitals. Though dirty old priests might have taken guilty pleasure from contemplating them, the rest of us are still allowed to see them. More reticence is observed with female figures, mainly because female models were hard to come by, but the first genuinely female nudes were often pubescent or prepubescent. The closet Venuses of Cranach and Baldung, for example, have the undeveloped hips, small, hard, high breasts and pallid nipples of 13-year-olds. Botticelli’s Venus is hardly older. Greuze’s girls, with their white bosoms glimpsed through disordered clothing and tear-filled eyes, are not only very young but violated as well. Bouguereau’s Cupidon (1875) and Child at Bath (1886) are far more disturbing images of vulnerable immaturity than anything created by Henson, but paint may do what photography may not. If Henson had painted his young subjects, the police would have no situation to investigate. (Greer 2008)

This last point is important, I think. Even though there might have been a time when Henson’s subject matter would have been considered acceptable, the way these images are produced – as photographs – adds another layer of complexity to this debate. Often, we tend to think of photographs as factual – as having a certain indexical connection to the ‘real’ world. This correlation, while questionable, has been used to distinguish the mediums of photography and painting, with the latter commonly viewed as illusory or further removed from reality, in part through its association with the realms of the artist’s imagination, creativity and uniqueness. So an element of the anxiety generated by Henson’s images is due to their status as photographs, which in the minds of some people are ‘evidence’ of reality, as well as too easily reproducible and distributable.

The locations where these images are consumed play a part, too. You don’t need to visit a gallery any more to see artworks like Henson’s, which can be easily accessed on the Internet, alongside a host of other images of children produced for commercial consumption – or, more troubling, for sexual gratification. Changing modes of dissemination and reception add to the confusion between art and pornography, as well as other visual forms, for that matter. The response to Henson’s photographs also needs to be understood in light of increased awareness of child sexual abuse and a growing concern over the sexualisation of children in popular and consumer culture. Remember, Henson has been taking photos like this for many years without controversy, yet recently his practice has been considered unacceptable by some groups as a society’s views on childhood start to shift.

What this example illustrates is how social, cultural, political and technological changes have altered the way images are made, as well as how they circulate and how we make sense of them. It raises valid and important points for debate about the ethics and legalities of image-making, as well as what constitutes art. Incidents like these force us to confront the status of the image in today’s world. What function do images serve? How do we understand the role and circulation of images – photographs, cartoons, computer-generated images (CGI), paintings, film and the like? How might we distinguish between different types of images? Is this possible? Or desirable? And how do we resolve matters when the lines between art and mass culture become blurred? This chapter is designed to introduce readers to the changing nature of the image, in order to help us make sense of these kinds of debates occurring within the visual arts, and the realm of image culture more broadly. Baudrillard’s writings, especially his notions of the simulacra, hyperreality and the transaesthetic, can give us some clues as to how images have worked historically, and the changing relationship between ‘representation’ and ‘reality’ which have led us to where we find ourselves today – in an era characterised by simulation and virtuality.

Transaesthetics

One of the ways that we can think about the Henson incident, and other examples like it, is in terms of what Baudrillard has described as transaesthetics. Defined by Baudrillard as ‘the moment when modernity exploded on us’ (Baudrillard 1993b: 3), there are certain characteristics he attributes to the transaesthetic. Firstly, it is typified by ‘the mixing up of all cultures and all styles’ (Baudrillard 1993b: 12). Baudrillard says that it is getting harder to distinguish clearly between art and other visual forms in contemporary culture because the categories used to separate things from each other have started to crumble. In the case of Henson’s photographs, they aren’t solely interpreted as art because their content – the naked body – also associates them with pornography. In another way, Henson’s images resemble glossy magazine advertisements, with both employing the medium of photography to construct their images. The translucent skin of the subjects he depicts glisten against their dark backdrops in a way that is not dissimilar to that of styled, angular fashion models. Indeed, the criticism of Henson’s use of young girls has been that it is the equivalent of the fashion industry’s. His pictures have been likened to film stills, and often appear in magazines, as well as on the Internet, which complicates the distinction between art and commercial culture even more. Just as his photographs capture the zone between day and night, male and female, sinister and seductive, adult and child, so too do they defy easy classification.

Henson’s photographs also support Baudrillard’s claim that the transaesthetic moment is one where everything has become aestheticised – that is, manufactured into a sign for consumption. To illustrate his point Baudrillard gives the example of politics being turned into a spectacle. As occurred with the American electoral primaries of 2008 that saw Hillary Clinton pitted against Barack Obama for the democratic nomination for president, policies and principles are subsumed by a focus on appearances to the extent that looks become a signal of reliability, trustworthiness and suitability. To quote Baudrillard,

everything aestheticises itself: politics aestheticises itself into spectacle, sex into advertising and pornography and the whole gamut of activities into what is held to be called culture, which is something totally different from art; this culture is an advertising and media semiologising process which invades everything. (Baudrillard 1992:10)

Baudrillard refers to this aestheticisation of all objects and forms as the ‘Xerox degree of culture’ (Baudrillard 1992: 10). Returning to the example of Henson’s photographs, we could argue that young adulthood, androgyny, or even art itself is made over as a sign to be consumed visually alongside a parade of other symbols and representations. We interpret these artworks in relation to the images we are familiar with from other visual sites, like cinema, pornography, fashion advertising and the history of Western art. This confused cultural space where Henson’s photographs are produced and received reflects the postmodern breakdown of the divide between high art and low or mass culture – a defining feature of the cultural condition of late capitalism (Jameson 1991: 112).

Not only does the subject matter of Henson’s photographs confound catergorisation, but the spaces in which they circulate further complicates their status. Along with the invasion of all genres and styles by each other, the transaesthetic is bolstered by the circulation of images in diverse spaces and across vast distances, enabled by instantaneous, immersive, mass-communication technologies like the Internet. Unlike the days when one went to a gallery to look at art, globalised media has made art much more accessible and reproducible. No longer confined to, or contained within, a particular place, it can reach more people in more locations than ever before. The flipside, though, is how can audiences be sure that what they are looking at is art when it is not defined by its gallery context? What’s more, in true DIY style, the interactive nature of new technologies enable almost anyone to create and disseminate ‘art’ (Poster 2006: Chapter 11). As a result of these shifts in how images are made, interpreted, circulated and consumed, there is more and more uncertainty about which images serve what functions, for whom, and in what contexts. This leads us to wonder, ‘What counts as art?’

A critical point that Baudrillard makes about this transaesthetic state of affairs is that as the distinction between forms and genres become less and less defined, making aesthetic judgements about what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, tasteful or crass, also gets harder. This poses a problem for how we can meaningfully speak about art when it has ‘disappeared’ as a coherent category, and prompts us to question whether old modes of analysis can work effectively in this situation. I consider this dilemma in greater detail in the next chapter.

While it is useful to consider the production and circulation of images in an age of globalisation and information technologies, it is equally necessary to recognise that we have not always thought about images in these terms. In what is perhaps Baudrillard’s best-known book in the context of visual culture and the performing arts – Simulacra and Simulation – Baudrillard demonstrates that images have served different functions throughout history. The image has changed from reflecting reality, to masking reality, to masking the absence of reality, to having no relation to reality whatsoever (Baudrillard 1994b: 6). But even before he traced these phases, Baudrillard identified the changing status of the image in Symbolic Exchange and Death (1993a), where he proposed three orders of simulacra (meaning ‘appearance’ or ‘likeness’) to describe the different ways that images have been produced, circulated and used, and our relationship to them. A fourth order has since been added. The rest of this chapter will consider the four classificatory orders of simulacra that Baudrillard proposes. By contemplating the purpose of images in society – and crucially, their value – Baudrillard’s theory of the simulacra can help visual arts proponents understand the role images play in moulding perceptions of reality and its representation.

First-order simulacrum

When Baudrillard talks about the first order of the simulacra, he is referring to the period from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. Of course images existed prior to this, yet according to Baudrillard they occupied a pre-modern era of social relations characterised by ‘symbolic exchange’ – a time before objects accumulated value in the economic or aesthetic sense that we are familiar with today. Baudrillard explains that images used to play a part in ritual, like the icons of Byzantine art, whose circulation was restricted to their sacred function (Baudrillard 1993a: 50). Each icon had a specific purpose and singular importance in forging collective ties through rituals and ceremonies. It is during the Classical period that Baudrillard claims the social function of the sign changes from one of maintaining social relations to one of hiding the fact that signs can no longer play that particular role in a world based on universal or generalised value systems. Put simply, he is saying that images have moved from being ritualistic to aesthetic.

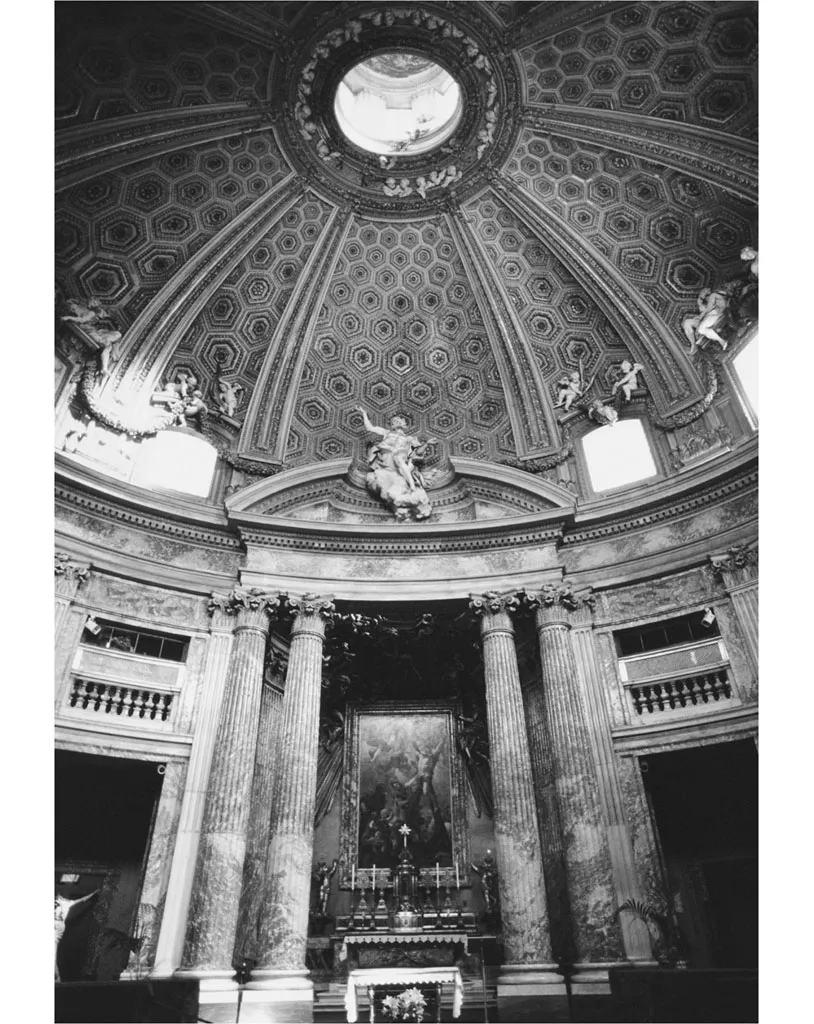

In order to grasp better this distinction, let’s turn to a well-known example from Western architecture during this period – the Jesuit church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome, built from 1658–78 (Figure 1). Designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the interiors of this structure display the hallmarks of Baroque architecture. Based on an oval floorplan, its centrepiece is a high altar illuminated by a flood of yellow light streaming in from a magnificent dome overhead. The structure is richly decorated throughout with red marble, gold detailing, intricate sculptures and elaborately tiled floors. Its ornate arches and cornices, as well as its domed roof, give the building its sculptural qualities, as well as fostering a sense of grandeur and awe at the pure spectacle of such frivolous embellishments. By overwhelming the senses with a riot of ornamentation, Sant’Andrea al Quirinale masks the fact that at its heart is a symbolic loss. For Baudrillard, in the first-order simulacrum the sign or image can only simulate the ‘symbolic obligation’, or worth it once had, that was generated by its sacred and specific role. That is, images no longer foster ritual relations but instead connote status – they now work to spread religious devotion, ‘aiming at control of a pacified society’ and cementing the power of the Church (Baudrillard 1993a: 53).

The Baroque excess and theatricality of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale also illustrates the changing nature of the image from something that was once restricted and limited in its circulation to something that is made increasingly accessible via public display. The plethora of paintings, frescoes and sculptures throughout the church and its side chapels is an example of a trend observed by Baudrillard whereby images are being made readily available to the masses. For Baudrillard, this explosion of images is directly associated with the loss of symbolic exchange that characterised ritualistic and feudal societies, and the subsequent emergence of a semiotic order of value in which images and signs function to homogenise and order the individual, random and unique aspects of the natural world. Signs are accorded a referent in nature – they are interpretations of the world, and hence allow for an arbitrary relation between a signifier and signified to be forged.

1. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1658–78, Church of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (Rome)

According to Baudrillard, as the image loses its anthropological status and becomes aestheticised it must accrue value in another way, which is by ‘giving the appearance that it is bound to the world’ (Baudrillard 1993a: 51). During this phase of simulation, Baudrillard notices that representations aim to reproduce nature in the form of an imitation. We can see this in stucco, a type of plasterwork that enables the rendering of objects in three dimensions, and which is a defining feature of Baroque décor. Nestled around the dome of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale are groups of stucco putti – or cherubs – among fruit and flowers. And while decorative objects like the cherubs and ornamental flora of the church’s interior don’t look necessarily look ‘natural’, they function to create a sense of universal order, h...