![]()

CHAPTER 1

MYSTICAL ROLES FOR ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egypt has long provided inspiration for those who sought to advance mystical, theological and philosophical views, and to support these by arguing that they reflected a heritage of ancient knowledge. They may identify themselves, or be described as, Hermeticists, Rosicrucians, members of a Freemasonry order, Theosophists, Anthroposophical, adherents of a New Age movement, or followers of the original true Egyptian religion as Kemetists. And today they may frame their alternative Egypt in secular terms: mysterious more than mystical. For two millennia creators and supporters of such ideas have turned to an image of ancient Egypt as their authority.

Egypt under the pharaohs – the three millennia from the First Dynasty until the death of Cleopatra in 30 BCE – has brought special fascination to a broad public of readers and travellers as well as serious scholars. Multiple images of ancient Egypt have influenced architecture and design, and form part of popular culture as well as education. The fascination of the period has made ancient Egypt a standard topic in any series of illustrated children's books, a sure drawcard for a museum exhibition, an element of many school syllabi and the subject of innumerable television documentaries. Novels and movies build on, and reinforce, images of ancient Egypt. Serious books have long presented, and re-presented, the history and society, the art and archaeology of the ancient Nile Valley, as uncovered by study and research by historians, linguists, archaeologists and specialists in ancient technology. In modern times up to 13 million foreigners have visited Egypt annually, the majority drawn to view the remains of the ancient civilisation.

Figure 1.1 Mystical Egypt: a tour advertisement from the USA, 2012.

Perhaps the largest mystery remaining in the study of ancient Egypt is why people have continued to create imagined and fanciful pasts for a period and place that has been so well documented. Pharaonic Egypt has provided the modern world with an excess of inscriptions and finds from excavations, with historical and archaeological studies on every matter of detail: a wealth of material has survived in the Nile Valley and the delta, deserts and oases that border it. The history, religion and ideas, social and economic structure, technology and skills of Pharaonic Egypt have been the subject of innumerable accounts, analyses and discussions since the expansion of epigraphic work from the mid-nineteenth century and the explosion of archaeological studies thereafter. Debates on matters of detail and analysis continue in an active international field of scholarship, but within a common core of understanding.

In contrast to all of this scholarship, numerous writers and speakers and subsequently film-makers and website hosts have imposed on ancient Egypt, perhaps more than any other ancient civilisation, their own theories: mysteries of the pyramids, riddles of the sphinx, lost wisdom of the ancients (called ‘Egyptosophy' in a survey by Erik Hornung). And Egypt has been used to provide support for alternative world histories, involving lost civilisations, ancient maritime migrations across the Atlantic or Pacific oceans, or the past presence of aliens visiting from other planets or galaxies. Ancient Egypt has become a serial victim. But while the models and details may be new and ever-changing, they follow an old pattern, an esoteric tradition, of attributing to ancient Egypt special knowledge and spiritual insights.

EMERGENCE OF KNOWLEDGE

What is not surprising is that before the textual translations and the archaeological work of the later nineteenth century, the ancient ruins of Egypt stimulated widespread comment and speculation. We cannot pass the same critical judgements on the past images that we might apply in our contemporary dismissal of wild ideas and invented constructions. For Egypt does present some of the most remarkable testimonials of the ancient world, demanding understanding and explanation. Massive pyramids of stone, ruined temples and tombs with detailed friezes showing gods and kings, inscriptions on distant rock faces, and the brilliantly crafted and beautiful antiquities admired and traded widely – all these have inspired outsiders' esteem and wonder since classical times. When Greek writer Herodotus in the mid-fifth century BCE visited Egypt, for the previous 75 years part of the Persian Empire, he was yet another inquiring tourist in a land where the first pyramids were already 2,100 years old. Like all tourists, he wondered at their meaning and origins and found local people willing to entertain him with stories. In the absence of better explanations now available, the readers of Renaissance and even Enlightenment Europe chose to rely on such observations of travellers and writers from the classical era.

Despite – or perhaps because of – Persian rule, the cults of the Egyptian gods remained strong and active at the time of Herodotus' visit, and Persian policy was to avoid disrupting local cults. He observed and reported on what he saw and was told of contemporary practice and beliefs; and he noted what heritage and background the fifth-century priests claimed for their cults.

They also told me that the Egyptians first brought into use the names of the twelve gods, which the Greeks took over from them, and were the first to assign altars and images and temples to the gods, and to carve figures in stone […] They are religious to excess, beyond any other nation in the world […] The names of nearly all the gods came to Greece from Egypt.1

There is little from Herodotus which is too fanciful or beyond the range of probability: where he is suggesting hypotheses on geography or the flow of the Nile, he says they are such. The priests and others (no doubt some imaginative interpreters and guides) recounted to him myths and legends and their interpretations of much earlier Egyptian history, including pharaohs associated with the Giza pyramids, and while these stories may have no historical validity, the Greek spelling of names persisted in later use. Even though the narratives recorded by Herodotus and other classical writers may lack historical substance, they fall within the range of other stories of the period in the Mediterranean: they do not extend to the mystical reconstructions of some modern writers, though the rituals of Egyptian priests continued to fascinate visitors. When Alexander the Great conquered Persian Egypt in 332 BCE he did not impose Greek culture and deities; instead he claimed an identity as the son of the deity Amun.

Writing in the first century BCE, Greek historian Diodorus Siculus summarised the ancient perspective: Egypt was ‘the place where mythology places the origin of the gods, where the earliest observations of the stars are said to have been made and where, further, many noteworthy deeds of great men are recorded'.2 He continued:

Greeks, who have won fame for their wisdom and learning, visited Egypt in ancient times, in order to become acquainted with its customs and learning […] For the priests of Egypt […] offer proofs from the branch of learning which each one of these men pursued, arguing that all the things for which they were admired among the Greeks were transferred from Egypt.3

But with the growth in Egypt of (Coptic) Christianity and then the arrival of Islam in the mid-seventh century CE, pagan and polytheistic ancient Egypt was regarded by many with loathing rather than the admiration or the fascination of the Greco–Roman world.

Medieval and even later European images of Egypt were influenced by biblical sources as much as classical, such as interpretations of the pyramids as granaries built by Joseph for the pharaoh, or built by Hebrew slaves before the Exodus. A short chronology of the earth was assumed from biblical literature, with creation about 4,000 years before Christ. To many this meant ancient Egypt's origins were close to those of mankind itself – or, at least, far closer than the writer's day; in contrast, Sir Isaac Newton, while accepting a creation date around 4000 BCE, argued in The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728) for a lower chronology of ancient Egypt.

By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many travellers from the Christian and Muslim worlds had visited, written about or illustrated the standing remains of ancient Egypt as well as carrying off portable antiquities. But the nineteenth century transformed Egypt from a place of puzzlement and wonder to restore its place in European understanding of human history. Napoleon's expedition of conquest in Egypt (1798–1801) was accompanied by scholars and scientists to travel and study these sites, and a major outcome for scholarship was the publication in Paris between 1809 and 1829 of the multiple volumes in large format of the Description de l'Égypte. An important by-product of the invasion was the acquisition by the French and subsequent confiscation by the British of the trilingual Rosetta Stone, which assisted linguists such as Thomas Young and especially Jean-François Champollion (announced in 1822) in the decipherment of ancient Egypt's hieroglyphic writing system. The many inscriptions on museum objects and recorded from Egyptian monuments could then allow Egyptian voices to explain themselves, with numerous translations published in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Excavation of sites and recording of their relics for more than museum display could develop under the antiquities administration established in 1858 under Auguste Mariette. Scientific field research proper began later, with an explosion of archaeological excavation, removal of finds overseas for study and recording of local monuments in the half-century from Flinders Petrie working in Egypt in the 1880s until the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922–32, after which Egyptian legislation limited the export of finds. The number of annual expeditions involving excavation and recording in recent years has been massive, slowed only by the political crisis in Egypt, with up to 240 current or recent foreign projects listed by the government's Supreme Council of Antiquities in addition to research and work by Egyptian teams. This has resulted in too much, not too little, information, crowding the museum stores and placing publication demands on research teams. The University of Munich's Egyptological Bibliographical Database listed 53,000 publications in Egyptology which have appeared after 1978.

All the new information allowed new historical syntheses. German scholar Heinrich Karl Brugsch compiled a lengthy history of Egypt in 1859, extended to two detailed volumes in its second edition (1877). By 1902 British Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge could compile an eight-volume history of ancient Egypt, and successive survey volumes covered every aspect of the ancient society. This much greater knowledge inspired greater interest, but in turn that provided a context for ideas which rejected and conflicted with the scholarly knowledge and understanding that had emerged: alternative and invented Egypts.

MYSTIC KNOWLEDGE AND ESOTERIC CULTS: HERMETICISM AND BEYOND

There is a long history to the idea that ancient Egypt possessed access to mystic insights and esoteric knowledge. Authors from the ancient Greek and Roman worlds credited the foundations of their religion, art and architecture to Egypt, attributing to Egyptian priests discoveries in mathematics, astronomy and other sciences. Even more direct links were created, such as assigning Egyptian ancestry to the royal family of Argos (considered forebears of Alexander the Great), and putting Egypt on the itinerary of past heroes and historical figures. To some Greek philosophers and other writers, an imagined past Egyptian state could serve as a model of the ideal. The classical writers introduced a misunderstanding of Egyptian formal script which would persist for two millennia: the idea that the individual signs they called Hieroglyphs (literally ‘sacred carvings') contained esoteric knowledge and were all allegorical or direct representations of their visible subject (the most common actually represent consonants in alphabetical, biliteral or triliteral form).

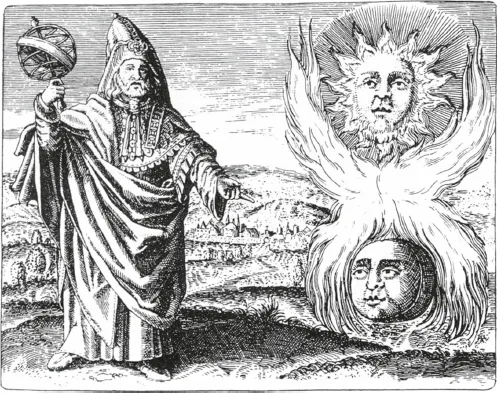

Within the Roman Empire there developed cults of the Egyptian gods Isis (with examples such as the Temple of Isis at Pompeii) and Osiris (or Serapis, thought by some to be a composite of Osiris and Apis). This went alongside identifying some of their own deities with those of Egypt. Other traditions developed to assign special mystical knowledge and insights to Hermes Trismegistus (Hermes Thrice Great), a figure who combined aspects of the Egyptian god Thoth with those of the Greek god Hermes, deities whose credits including writing and magic. Hermetic traditions had wide popular followings in and beyond Ptolemaic Egypt, reflecting a fascination with the heritage of ancient Egypt now under foreign rule. Magic spells, as well as alchemy, were associated with these cults.

Hermetic writings such as the Asclepius (which we have in Latin translation) and the Corpus Hermeticum, written in Greek within the Roman Empire of the early centuries CE, purported to report detailed mystical insights of Hermes Trismegistus.

Figure 1.2 Hermes Trismegistus – seventeenth-century image.

Egypt is an image of heaven […] everything governed and moved in heaven came down to Egypt and was transferred there. If truth were told, our land is the temple of the whole world.4

Among Hermetic ideas was the view that sacred Egyptian texts had been buried in the (now lost) tomb of Alexander the Great.

A continuity of the Hermetic tradition is seen in the medieval era in both the Middle East and Europe, with Hermes Trismegistus regarded as one of the great (but now clearly human) ancient prophets. Early Islamic scholars identified the Qur'anic prophet Idris with Hermes – ninth-century author al-Yaq‛ubi claiming that Idris was the first man to use writing. The core Arabic Hermetic tradition has been dated by Islamicist scholar Michael Cook to the eleventh century, with new writings originating in the Muslim world, though not linked through Coptic Christianity to the earlier traditions. It was influential in Egypt itself, though possibly originating further east. Under titles such as Akhbar al-Zaman (History of Time), images were given of an ancient Egypt possessing a high level of science, with knowledge extending back to antediluvian priests of Egypt, and a Hermes whose attributes even extended to building pyramids.

The twelfth-century Andalusian Muslim writer on the history of science, Sa‛id al-Andalusi, wrote that ‘Hermes, a resident of Upper Egypt before the Flood, was the source of all science'. Muslim traditions credited him with contributions to astronomy, medicine and poetry, as well as building the pyramids and recording knowledge there.

Egyptologist Erik Iversen has argued that in medieval Europe ‘an almost mystical veneration for the wisdom of the Egyptians lived on'.5 This was a period in which few Europeans reached Egypt, and little was experienced directly of Egyptian monuments and antiquities. The less that was known about ancient Egypt, the greater could be the sense of ancient – if heathen – knowledge. But the ancient Hermetic texts were known to Christian theologians and scholars.

Two images of ancient Egypt were interwoven, but both credited it with great power. The Christian and Muslim image took from the Jewish Pentateuch the story of the Captivity from Joseph to Moses under powerful pharaohs, and the maintenance of Jewish monotheism under alien oppression. The classical authors – known to scholars in the Arabic-speaking world at least as much as in Europe – provided the image of Egyptian antecedents to Greek culture with a priestly cult possessing skills and knowledge.

An interest in Hermeticism saw a revival with the Renaissance, initially not so much as a challenge to Christianity as a source to access ancient Egyptian knowledge of magic. The early Hermetic writings were published in translated editions in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, attracting interest from figures ...