![]()

SECTION II

ARTISTIC PRODUCTION AND CONTEMPORARY DISCOURSES

![]()

7

THE CRISIS OF BELONGING: ON THE POLITICS OF ART PRACTICE IN CONTEMPORARY IRAN

HAMID KESHMIRSHEKAN

The issue of ‘belonging’, which is related to localised historical and cultural landscapes, fuels a complex debate in Iranian art today, and perhaps more generally in the Middle East. I will argue here that the lack of critical discourse regarding this issue has left individual artists to pursue their own solutions to the question and to generate artistic strategies that are relevant to the demands of contemporaneity – a concept that itself remains undertheorised. I will then explore the strategies pursued by artists in the Iranian context, and the wider politics of art practice relating to these fundamental yet unresolved questions.

Rather than offering a broad summary, I will examine this concern through the works of a number of artists, situating them with reference to the concepts of identity, ethnicity and transnational contemporaneity. With reference to selected works, I will also consider how artists enact a politics of resistance to explicit ethno-cultural identity markers – that is, to essentialised cultural views that often reduce their works to geopolitical concepts. Using contemporary discourses on globalised art, their art practice aims to revisit a well-established debate within art-historical discourse: namely, whether art should have creative autonomy, or whether it is only ever determined by its context. As will become clear, for some artists, artistic practice is an intellectual and activist project that serves as a fitting site for the possibility of a responsible and sociopolitical art.1 In the second part, through five case studies of artists’ works, I will examine how artists act against the erasure of contextual frames, demonstrating an awareness of the fact that contemporary art is capable of transcending the politics of location. I will discuss the current dilemma of how contemporary Iranian artists have responded to Iran’s social and cultural complexities.

Contemporary Iranian art, in the process of adaptation to and appropriation of the Euro-American artistic paradigms, has incorporated elements of so-called global contemporary art while seeking to create and reflect the phenomena of its own contemporaneity.2 This alternative context of contemporaneity is obviously a response to canonical discourses, and ideally aims, in turn, to inscribe new discursive formations in the contemporary era. Unsurprisingly, issues concerning the politics of identity have taken centre stage within this emerging context, and have thus shaped and influenced artistic practice.

A familiar debate within this arena concerns whether it is possible to articulate specific cultural issues (usually denoted by the cultural past) while addressing contemporaneous issues related to the wider and broader global field. This reveals deep-rooted anxieties that relate to the issue of cultural belonging and identity, and their possible affinity with international concerns, and poses the important question: Is it possible to open up an art practice and discourse that are contemporary and global, while also being indigenous and specific?

It might first be useful to consider the origin of some of these practices that have sought to engage with the global arena.

As I have argued elsewhere, by the end of the 1990s a number of young artists, in rather a short time, increasingly began to make use of new and unprecedented means of media. At the same time, artworks appeared that were in line with contemporary art processes incorporating new viewpoints that reflected existing circumstances in Iran. As with contemporaneity, the impetus for this came partly from the international arena and partly from domestic conditions, where the need to record reality in a transitional era in all its shifting forms had become more urgent. The emergence of newer media and various contemporary approaches arguably enabled a more sustained critical and direct social address than was possible with earlier forms of Iranian modernism.3 This new trend was established first in the early 2000s, when it found support in official institutions – in particular the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA).4

A common thread uniting these artists was a yearning to be in the here-and-now: to incorporate into the experiences of globalised internationalism in a simultaneous and concrete practice. The postscript for the contemporary artist was now defined by their need to be in the ‘contemporary’, rather than to produce a belated or anachronistic response to the everyday. Inevitably, then, this drive to comply with global value systems would entail an understanding of global discourses on art. There seemed to be an insatiable demand to reveal what might be defined as ethno-cultural identity markers, often encapsulated by specific, essentialised symbols: subjects such as cultural heritage, tradition, and gendered experience, which would also comply with typical definitions of cultural authenticity.5 This insatiable demand would in return affect choices of subject matter and imagery. This often leads to the prohibition of cultural aspirations or forms of address when artwork is exhibited. The impulse to suppress cultural statements or gestures within the exhibiting establishment is a response to the presumed demands of the cosmopolitan art world, rather than to domestic sensibilities. References have been made in Iranian art to the issues from traditional imaginary and cultural frameworks to vivid political and controversial subjects6 (Fig. 7.1). Exploring these themes in art would be a strategy whose parameters are at least clear to win recognition internationally, although not necessarily locally. Thus, this strategy often goes unchallenged by practising artists who wish to be part of this international system. Examples of a nostalgic aesthetic approach towards local and national imaginaries are not hard to find (Fig. 7.2).

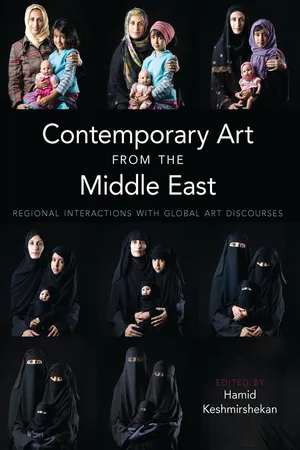

FIG. 7.1 Gohar Dashti, from the Me, She and the Others series, 2009, C Print, courtesy of the artist.

Here one should beware of the issue of the essentially dissimilar reception and reading of these artistic strategies which aim to reconcile cultural specificities with international demands at home to the international scene. Artworks that are praised by the world exhibition centres as strongly representative of the cultural mood of the country are fiercely criticised at home, as it is said that they aim only to win the approval of ‘the Other’. Despite the fact that these artists are more widely represented in the current surge of interest in contemporary Iranian art – and are indeed associated with such trend-setting schemes – there is open criticism of this situation at home, where it is argued that their position is based on ‘stereotyping’ of these trends.7

The tensions between the two opposing movements – representing the claims of cultural homogenisation on one hand, and of cultural heterogenisation on the other – are clearly reflected in the products developed by artists: global forms, aesthetics, functions and concepts versus local values and desires. But art cannot be seen simply as a linear story in which a local art is introduced onto a global platform. The questions that result from this are: How do local languages adopt to a globalised art discourse? How does hegemonic language of art discourse affect an artist for whom it is not his or her mother tongue?8 Intellectual and artistic strategies are central to the challenge of dealing with this hegemonic structure.

The issue of cultural otherness has also been framed by the Iranian state, although making use of different ideological resources from what the international almost unanimous value systems would propose. The question of a return to a glorified past and political stance against modernity, which gathered momentum in the 1979 Revolution, is still strongly present in the cultural policy of the state. The use of various materials and themes from native sources to construct ‘independent’ or ‘authentic’ works, supporting the idea of cultural specificity and indigenous expression in artwork, has been partly the result of this formulation.9 The materialisation of this idea can be seen in the works of artists who are still influenced by such debates as that concerning the creation of a unique artistic identity within the cultural domain of the country, aired in particular during the 1960s. This decade had already seen the influential role played on the art scene by the so-called neo-traditionalist Saqqa-khaneh movement.10 The artists affiliated with this movement attempted to reconcile the cultural heritage of the past with the language of modern art (Figs 7.3 and 7.4). The use of ancient, traditional or national materials in order for their work to be identified specifically as ‘Iranian’ was partly the result of nativist and nationalist beliefs that had been variously presented throughout the recent history of Iranian art. The artists appropriated Western canon and discourses, but looked for inspiration in native popular culture. The result was a new form of art inspired by contemporary trends in the West while at the same time questioning Eurocentric hegemony, as well as incorporating elements from local cultures in order to promote more polycentric and alternative aesthetics. These artisits sought to situate their practice in the broader intellectual context of their era, and devoted considerable effort to building new institutional frameworks of exhibition, patronage and reception for modern art. Interestingly, in addition to the wide domestic realisation that they received, their works were also successful in gaining international recognition at the time, as it was taken to constitute the perfect way of representing Iranian, or more broadly Middle Eastern, art.

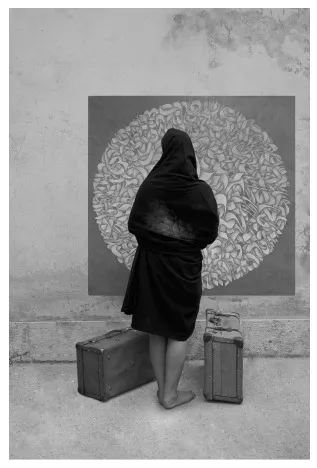

FIG. 7.2 Arman Stepanian, from the New Art series, 2008, C Print, 100 × 70 cm, courtesy...