![]()

CHAPTER 1

CRIMEA AND THE BLACK SEA: THEMES IN ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY

Crimea's geography

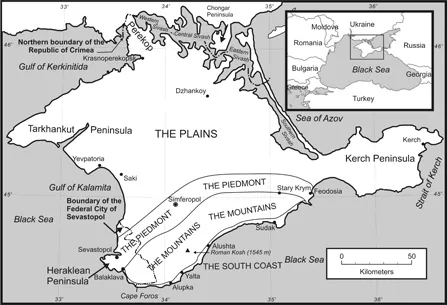

The Crimean Peninsula occupies a territory of approximately 27,000 km2; an area about the size of the state of Massachusetts, or somewhere between that of Macedonia and Rwanda. Crimea is bounded to the west and south by the Black Sea, to the east and northeast by the Azov Sea, and to the north by the Sivash—a lagoonal system connected to the Azov Sea. The extreme latitudes are N 46° 10' 26” at the far north of the Perekop Isthmus, and N 43° 23' 11” at Cape Foros (Figure 1.1).

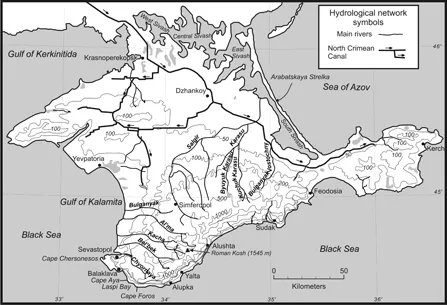

The territory of the Crimean Peninsula is composed of the plains, the piedmont and the mountains (see Figure 1.1). The summit of the mountains consists of a series of karstic plateaus known as yailas. The highest is the Roman Kosh (1,545 m), located in the Babugan Yaila in the central part of the Crimean Mountains. The mountains present an asymmetric topography, gentler to the north and steep on the south (Figure 1.2). The major river basins are located on the northern slopes of the mountains. The largest rivers are Salgir, Al'ma, Kacha, Bel'bek and Chyornaya. The streams of the southern slopes consist mainly of mountain torrents (Figure 1.2). The natural lakes of Crimea comprise saline shallow bodies of water scattered through the north and west of the plains and along the coasts of the Kerch Peninsula.

Modifications to the drainage system are seen through the numerous dams and canals. The most important of these canals is the North Crimean Canal (NCC) (Figure 1.2). Finished in the 1960s as part of Nikita Khrushchev's Virgin Lands Campaign, the NCC provides water for crops in an area naturally too dry or unpredictably moist for large-scale agriculture. The canal also serves as a water supply to towns, as well as being used for recreational activities (Figure 1.3). Although the NCC was an engineering marvel that had a practical economic purpose, it brought an end to the grasslands of the steppe. Since its completion, virtually all the steppe has been turned in to cropland.

Figure 1.1: The Crimean Peninsula: Physiographic regions.

Figure 1.2: The Crimean Peninsula: Topography and hydrological network, including the main canals.

Figure 1.3: The North Crimean Canal (branch of the Dnieper Canal) near the town of Dzhankoy. Besides irrigation, it is used for recreation and fishing.

Politically, since its annexation to the Russian Federation in March 2014, the Crimean Peninsula comprises the District of Crimea, which in turn is divided into the Republic of Crimea and the Federal City of Sevastopol (Figure 1.1). Although a subject of Russia, the Republic of Crimea has its own constitution and flag. The Federal City of Sevastopol is one of three cities with that status in the Russian Federation (the other cities being Moscow and Saint Petersburg).

The Republic of Crimea (the Autonomous Republic of Crimea under former Ukrainian rule) had a total population of 1,973,000 (as of 2007). Its capital city, Simferopol (340,000 inhabitants) is located on the piedmont on the Salgir River. Other major cities are Kerch (157,000), Yevpatoria (103,244), Feodosia (97,721) and Yalta (80,552). The Federal City of Sevastopol (the Municipality of Sevastopol under Ukrainian rule) had a population of 379,200 inhabitants (as of 2007). Its major cities are Sevastopol (342,000), Balaklava (30,000), and Inkerman (10,472). The total population of the Crimean Peninsula is 2,352,200, with a population density of 89 people per square kilometer. The main ethnic groups in the entire peninsula are Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar, followed by smaller groups such as Armenians, Jews, Byelorussians, Bulgarians, Greeks and Italians.

Russian is the most widespread language, although Ukrainian is also spoken by a minority. However, Crimean Tartar, a language of the Turkic branch of the Ural-Altaic family, is spoken among the growing Tartar population of Crimea. The most widespread religion is the Orthodox Christian faith, which is practised by a sizeable number of the Slavic inhabitants of the peninsula. Sunni Islam is practised mainly by the Tartar population. Additionally, Judaism and various Christian sects are practised by much smaller groups.

Biogeography and environmental history

This book presents and discusses aspects of Crimea's natural world in a dynamic and historical context. In this endeavor, the topic of the book—the making of Crimea—draws on disciplines such as geology, climatology, geomorphology, Quaternary science, biogeography and environmental history. But given the specific themes of the book (discussed in this chapter) the emphasis is on biogeography and environmental history.

Biogeography, or the study of spatial distribution and dynamics of living organisms, includes analysis of topics such as endemic and relict species, the evolution of communities, populations, biomes, and their strong links to geological history and climate change. The interaction of these biogeographical aspects of the peninsula with human societies is what constitutes the environmental history. In turn, biogeography and environmental history help us understand the modern landscape of Crimea; to comprehend complex environmental processes such as biodiversity and conservation issues; the potential for tourism; and offer guidelines for scientific studies on nature, history and archaeology.

As a biogeographically focused work, this book revisits many of the hypotheses and ideas put forward by Soviet biogeographers regarding the origin of Crimea's flora and ecosystems. The most frequently discussed of these hypotheses are the ones that try to explain the origin of the Mediterranean vegetation in southern Crimea. My approach to the problem is based on my own palynological and biogeographic research, taking into account the paleoclimatic, geological and ecological research carried out in recent years in the Black Sea region. The topic involves aspects of European glacial refugia of trees and boreal relict flora in the mountains. Recently, palynological studies by Ukrainian palynologist Natalia P. Gerasimenko have revealed more information on full-glacial vegetation in Crimea (Gerasimenko 2007). These studies have also been complemented with research on faunal remains associated with Neanderthal and modern human occupations during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, namely, the last interglacial–glacial cycle (Chabai, Marks and Monigal 1999, 2004).

Environmental history, unlike natural history, encompasses the presence of humans as modifiers and often builders of the environment. It focuses on human–environmental relations. Thus, for Crimea, an environmental history should start with the time when bands of hominins inhabited the peninsula during the Pleistocene. The Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), often referred to as cave men, inhabited Crimea from at least since the last interglacial period (128,000–115,000 years ago) until their demise and replacement by their successors, the anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens), sometime between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago. Afterwards, human history becomes more and more relevant to environmental history, since modifications of the environment increase, leading to the introduction of agriculture and further cultural developments.

In theory, there were hominids in Eurasia before the Neanderthals, but evidence of their presence in Crimea exists only in very few places. If such occupations were once widespread they are not visible or have been wiped out by erosion and other natural processes. The environmental history here, therefore, encompasses that part of prehistory that in Crimea is better known, which extends from the last interglacial period, through the last glaciation, and the postglacial period known as the Holocene.

Archaeology and history also have a decisive role in the reconstruction of environmental history. The archaeological record merges with the historical record some time before the beginning of the Common Era. Documents referring to the Crimean Peninsula appear together with Greek and Roman historians and geographers, who apparently wrote very little about it. Being on the edge of empires and classical influence, the northern Black Sea shores are known less than the Mediterranean core region but, as time passes, more descriptions and references appear, particularly during and after Byzantine rule of the peninsula (roughly from the third to the fifteenth centuries AD). Therefore, our understanding of human–environment relations across the various historical periods is still in the making and is constantly being updated, with more research projects currently underway.

The multiple aspects of biogeography and environmental history of any territory, regardless of its territorial size, are difficult to compress into a single volume. Furthermore, it is difficult to separate them as topics that are exclusively biogeographical or exclusively environmental history. This being so, the topics treated in this book follow seven main themes, described below.

Isolation and connection

In his novel, The Island of Crimea, Vassily Aksyonov, a dissident writer of the former Soviet Union, portrays Crimea as an island, whose geographical conditions allowed the White Russian Army to resist the Bolshevik conquest and to form a Russian Republic. In the novel, in the late 1970s the Republic of Crimea has evolved into a country in the sphere of the capitalist West. The idea of an island as portrayed by the novel is not difficult to imagine: just look at the map of Crimea. It is possible to see that the connection to the mainland is just a narrow isthmus, the Pekerop, which separates the Gulf of Kerkinitida from the Sivash lagoonal system (Figure 1.1).

The Perekop (isthmus, in Russian) has a minimum width of 2 km, an approximate length of 7 km, and a maximum elevation of 20 m above sea level. Today, the Perekop is not the only access to Crimea from the mainland: a road and a railway line connect the mainland with Crimea on the central part of the Sivash via the Chongar Peninsula through bridges across a strait no wider than 100 m and no deeper than 1 m. Another bridge connects the mainland with Arabatskaya Strelka on the eastern part of the Sivash. However, the traditional and historical land access to Crimea has been the Perekop.

The idea of insularity depicted in Aksyonov's novel has a strong parallel in writings about Crimea's natural history, biogeography, geology and archaeology. During the warm stages, or interglacials, the sea rose to levels similar to the modern one or even higher, suggesting possible flooding of the lowlands of the northern part of the peninsula, namely the Perekop and Sivash areas. Total separation from the mainland, created by a sea on what is now the Sivash region and the Perekop, has been proposed by archaeologists (e.g., Lazukov et al. 1981; Richter 2005; Chabai 2007) for the last interglacial (130,000–115,000 years ago), but its existence is doubtful as no stratigraphic evidence in this region has yet confirmed the existence of a strait connecting the Black Sea with the Sea of Azov (see discussion in Chapter 5).

Even if the alleged isolation did not occur, which is the opinion of the author, Crimea would still have been a functional island in the biogeographic sense. A harsh, hostile environment created by high salinization and unpalatable vegetation in northern Crimea would also act as a barrier similar to a sea. The picture is clear even in the historic landscape of northern Crimea today, so that the biogeographer Lev S. Berg (1950) considered the extensive salty dry steppes around the Sivash to act as a barrier to the movement of fauna and flora, thus adding to the biogeographic isolation of Crimea.

Yet the idea of isolation is not complete if it is not contrasted with the idea of connectedness, i.e., the suggestion that Crimea may have been connected with regions around the Black Sea other than through its present connection with the Ukrainian mainland. Like isolation, connectedness has also stirred lengthy discussions among naturalists and academics, and particularly geologists and botanists, who have always thought in terms of bridges between Crimea, the Caucasus, the Balkans and Asia Minor (modern territory of Turkey). This idea evolved into what is called the Pontida Hypothesis, which alludes to the existence of a former land bridge between the Crimean Mountains, the Caucasus and Asia Minor. As explained in Chapter 10, this idea has been dismissed by geologists and botanists themselves, and replaced with more modern hypotheses concerning changes in sea level in tandem with transitions between glacials and interglacials. Linked to the issue of isolation, connectedness and land bridges, are the concepts of biodiversity, endemisms and relicts, which have also been a hot topic in Crimean biogeography and conservation.

Biodiversity, or the number of species per area, is another biogeographic issue that accentuates the insularity–connectedness relation. Areas of high biodiversity in the world have been designated biodiversity hot spots, of which the Caucasus is one (Myers et al. 2000). Despite biogeographic affiliations with the Caucasus, the Crimean Mountains are not part of the Caucasian Biodiversity Hotspot. Species diversity in Crimea, although high by world standards, is low compared with that of the Caucasus (Biodiversity Support Program 1999). In view of this, and the previously mentioned issue on insularity, I offer in Chapter 10 an alternative interpretation of the biogeographic issues of biodiversity, endemics and relicts by characterizing the Crimean Mountains as a “functional island.”

The influence of the Black Sea

The Black Sea has had a tremendous influence on practically all aspects of Crimea's natural and cultural history. Firstly, the Black Sea influences the climate of the peninsula by providing a source of moisture and by preventing temperatures from attaining high and low extremes. Secondly, the Black Sea has been the main factor in the process of connection/isolation with the mainland. Finally, the Black Sea has been a carrier of natural and cultural agents in and out of the peninsula. For this reason, it is difficult to talk about aspects of biogeography and environmental history without acknowledging the surrounding sea as an important factor in shaping the Crimean landscape.

The origins of the names given to the Black Sea in antiquity are shrouded in mystery. While early classical works refer to it as Pontus Axenos (unwelcoming sea), presumably an allusion to the difficulties of navigation and to the storms, in late antiquity the name changed to Pontus Euxinus (the hospitable sea) (King 2004). The name “Black Sea” is as dubious as its predecessors. The name comes from the translation of the Turkish Kara Deniz—literally, Black Sea. Interestingly, the Turks refer to the Mediterranean Sea as Ak Deniz (White Sea). The meaning of these two names suggests that their country is between two remarkably different seas. Modern Turks refer to this difference in terms of weather: stormy and dark skies characterize the Black Sea, while nicer and more stable weather characterizes the Mediterranean. However, Charles King (2004) proposes that the early Greeks adopted the Iranian name Axenosi, from the Iranian word Axeinos (dark), which seems to suggest that the illusion to the blackness or darkness of the modern name originated in antiquity.

The Greek geographer Strabo (64 BC–24 AD) wrote extensively on the Black Sea. Strabo was originally from Amaseia (modern Amasya), near the northern coast of modern-day Turkey south of Sinop, which probably left him with a knowledge of many of the traits of the Black Sea from contact with sailors and fishermen. Although a geographer, Strabo is not particularly characterized as a traveler; most of his books are based on secondary sources, particularly from the Library of Alexandria (Hazel 2002). Therefore, the likelihood that he had ever traveled in Crimea and the northern shores of the Black Sea seem slim.

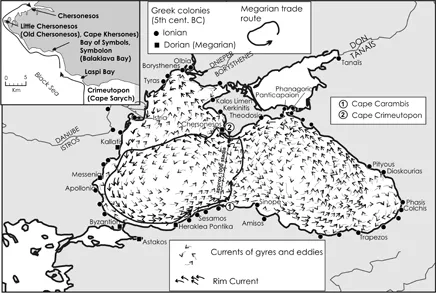

Figure 1.4: The Black Sea currents, Strabo’s Megarian route, and Greek colonies of the First Millennium BC.

One of the most interesting features of the Black Sea and Crimea that Strabo describes are the sea currents and their use by ancient Greek sailors (Figure 1.4). The most relevant fact related by Strabo on sea currents and sailing is his reference to the Megarian route. Named after the city of Megara, in the Greek mainland, the Megarians were an offshoot of the Dorian Greeks, who were successful in establishing cities and trade routes in the western half of the Black Sea basin (Hind 1998).

Strabo (2, 5, 22; 7, 4, 3) was the first to observe that a 1,000 stadia long line between Cape Crimeutopon on the southern Crimean coast, and Cape Carambis on the northern coast of modern Turkey, effectively partitioned the current into two seas (Figure 1.4). It is perhaps obvious that he also observed the two main gyres, then generating two currents, one in the west with counter-clockwise rotation and one in the east with clockwise rotation. The gear effect of the two gyres results in the counter-clockwise Rim Current, which was also important for cabotage navigation (Zolotaryev 1979). Thus, the Megarian route of colonization simply follows the Rim Current for the most part (Hind 1998). One example of this is the chain colonization of Dorian Greek cities, beginning with the mother town of Heraklea Pontika (present-day Ereğli) (Figu...