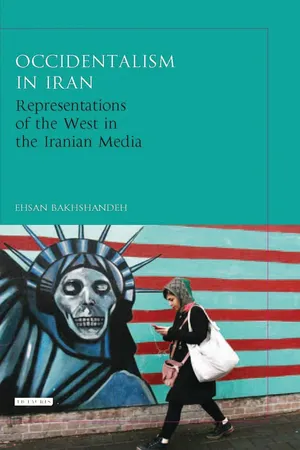

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE ‘OCCIDENTAL WEST’ VS ‘ORIENTAL EAST’

The West, as defined by the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, is the region in the Western hemisphere encompassing Europe, North America and Canada, contrasted with the East, which includes Asia and the Middle East. Geographically, the West today normally includes Europe and the overseas territories belonging to the Anglosphere, the Hispanidad, Lusosphere and the Francophonie.1

From the political point of view the concept of the West (versus the East), or the Occident (as opposed to the Orient), which emerged in the late nineteenth century, is a political construct and a dialogue between the Old World or Europe and the New World or the United States.2 According to Raymond Williams,3 the West–East distinction dates back to the Roman Empire era and to the separation between the Christian and Muslim worlds during the third and fifth centuries, even though Hobson attributes the rise of the West to the period between 500 and 1800.4

In his Twilight of the West,5 Coker describes the West as ‘an elusive’ term which sometimes includes even Japan (other authors agree, variously describing Japan as the ‘emblem of the East’,6 ‘Western-type society’,7 ‘honorary European’8), Russia and other countries such as Australia and New Zealand that are outside the institutions that have constituted the ‘Western community’ or ‘Western coalition or alliance’.

Studying the debate over the West between Hegel and Goethe, two of the most important thinkers of the nineteenth century, Coker recognises that the United States, as the most modern society in history, would be ‘the master builder’ of the Western world.9 Therefore, it might be inferred, as explained below by Coronil, that the United States is the representative of the Occident before the Orient.10 In other words, the West is exemplified by the United States;11 therefore, ‘West’ and ‘United States’ could be used interchangeably:

With the consolidation of US hegemony as a world power after 1945, the ‘West’ shifted its centre of gravity from Europe to ‘America’, and the United States became the dominant referent for the ‘West’. Because of this recentering of Western powers, ‘America’, ironically, is at times a metaphor for ‘Europe’.12

Zinkin defines the West as a cultural and not a geographical concept, which means ‘the countries of city corporations, free association, and Biblical religion’.13 In his analysis of the Western city and its comparison with the Eastern village, Zinkin highlights the role of the West in pioneering personal freedom, urbanisation, modernity and technology.

In the Western town all men started equal … There was no aristocracy of birth resting upon military prowess and monopolistic offices as there was in the countryside. Any man, if he was successful in his business and respected by his fellow citizens, could aspire to anything. But in Asia … real opportunity did not exist. There is no Asian equivalent for the Fuggers, Counts of the Empire, the Medici, Grand Dukes of Tuscany. In Asia government was carried on by the appointees of the monarch or the lord.14

Originally, Western philosophy, as contrasted with that of the East, began in the 1800s and continued in the 1900s with ideas such as the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and colonialism, which emanated mainly from Europe. The ideas of the West then spread so widely in the early twenty-first century and following the end of the Cold War (1945–91) that many modern and developed countries are to some extent influenced by different aspects of the Western or Occidentalist philosophy. Presenting a critical analysis of Jack Goody's The Theft of History (2006), Santos argues that from the sixteenth century onwards the West started to ‘impose its conceptions of past and future, of time and space, on the rest of the world’:15

It has thus made its values and institutions prevail, turning them into expressions of western exceptionalism, thereby concealing similarities and continuities with values and institutions existing in other regions of the world.16

Hobson observes that such a discourse of ‘racist-Eurocentrism or Orientalism’,17 which reached its peak in the nineteenth century, led to the formation of Orientalist and ‘civilisational-apartheid’ themes such as the superiority of the West to the East with the former being ‘exceptional, progressive and superior’ and the latter ‘regressive and inferior’.18

The struggle between the West (Occident) and the East (Orient), defined by Said as ‘mostly ideological oppositions’,19 is linked more to the history of imperialism and colonialism than modernism and its confrontation with traditionalism. Indeed, Buruma and Margalit try to demonstrate that the West is simply equal to ‘Roman imperialism, Anglo-American capitalism, Americanism, Crusader-Zionism and American imperialism’ and can be discussed through a thorough investigation of Occidentalism.20

Occidentalism: Orientalism in reverse or opposition?

Edward Said has divided the world into two ‘unequal halves’ of Orient and Occident.21 The relationship or, in Said's words, the ‘ontological and epistemological distinction’, between them is a ‘man-made’ relationship of power, domination and hegemony.22 In his seminal work on the Orient and Orientalism, Said explains how representations of the Orient in the literary works of Westerners have been a source of knowledge for the West about the East and the power the Occident exercised over the Orient. Said believes the West gained strength and built up its power through the ‘weakness’ of the East.23

In Said's view, Orientalism is a strategy of Western world domination that began with the domination of the United Kingdom and France (until World War II) and the United States (after the end of World War II) on the Orient. Throughout his book, Said tries to tell the reader that the West is wielding power over the East through his concept of Orientalism. He highlights the role culture played in the formation of ‘political and ideological’ Orientalism and how the latter ‘borrowed’ from the former.24

Orientalism offers a marvelous stance of the interrelations between society, history, and textuality; moreover, the cultural role played by the Orient in the West connects Orientalism with ideology, politics, and the logic of power…25

Said's work on Orientalism has been criticised widely, from issues related to the originality of his work,26 to questions of the basis of his theory of Orientalism27 and feminists complaints about the absence of any discussion of gender in the text.28

Despite criticisms, Orientalism has turned into a political discourse, dominating relations between the West and East. Orientalism is, however, one end of the spectrum. The other end is Occidentalism. Like its counterpart, Occidentalism is an overarching discourse that is employed with respect to historical context, although it is not yet as structured as Orientalism.29

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the word ‘Occidentalism’ in writings back to 1839, when Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine carried a story about an Iranian king, Soltan Mahmoud Ghaznavi (971–1030) – the ruler of the Persian Ghaznavid dynasty:30 ‘The Sultan Mahmoud and his Turkish subjects … have no taste for … the Occidentalism, the journalism, the budgetism, the parliamentaryism of the nineteenth Century.’31 Occidentalism can be discussed from both a general and political point of view. By definition, Occidentalism, as in the example of Soltan Mahmoud, accounts for any Occidental quality, style, character or spirit or any Western customs, institutions, characteristics, etc. More precisely, Occidentalism is the knowledge of the West (in terms of language, history, culture, etc.) in/by the East.

Similarly, an Occidentalist is either a student of Western languages, history, culture, etc. or a person who favours or advocates Western customs and ideas (Iranian intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad describes such Westernised people as ‘Westoxicated’, i.e. Eastern people who excessively devote themselves to adopting Western ideas).32

As stated above, the term Occidentalism and its derivatives were being used during the eighteenth century mostly in academic contexts to refer to Western customs. However, the term has taken a more political and ideological meaning, almost similar to its counterpart – Orientalism – which will be explained below. The very term ‘Occidentalism’ politically has generated some controversy in recent years as very few organised and fully-scholarly pieces have been written about it and the field remains much understudied. The major literature in the field could be attributed, but not limited, to the works of Carrier, Chen, Cole, Howard, Ning, Coronil, Boroujerdi, Venn, Buruma and Margalit, Furumizo, Bilgrami, Roth-Seneff, Friedman and Santos.33

According to Boroujerdi, the concept of Occidentalism in the Orient was formulated by the Syrian critic Jalal Sadik al-Azm.34 Writing in an essay in 1981, al-Azm proposes the concept of ‘Orientalism in reverse’. In it, he accepts the basic dichotomy of East and West and reiterates that only Islam is authentic and a solution to the problems.

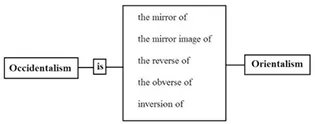

Reviewing the literature related to Occidentalism, one can identify a group of similar vocabularies used to define Occidentalism. They include words such as ‘mirror’, ‘mirror image’, ‘reverse’, ‘obverse’ and ‘inversion’, which denote that the signified is the same as the signifier.

For example, Coronil defines Occidentalism as ‘not Orientalism in reverse’35 but its dark side, as in a mirror; which means Occidentalism is in opposition to Orientalism. Such a definition has been reiterated by Ning, who defines Occidentalism as ‘opposed to Orientalism’.36 In other definitions, Howard believes Occidentalism is the ‘obverse of Orientalism’37 and Cole defines it as ‘not the mirror-image’ of Orientalism,38 while Friedman describes Occidentalism as ‘an inversion of the former Orientalism’ (Figure 1.1).39

Figure 1.1 One definition of Occidentalism using similar words. Source: author.

Santos has identified ‘two very distinct’ conceptions with regards to the definition of Occidentalism:40

First, Occidentalism as a counter-image of Orientalism: the image that the ‘others’, the victims of Western Orientalism, construct concerning the West. Second, Occidentalism as a double image of Orientalism: the image the West has of itself when it subjects the ‘others’ to Orientalism.41

He further explains that the first conception is a ‘reciprocity trap’, as victims of Western stereotypes have ‘the same power’ to construct stereotypes of the West, while the second conception is related to the ‘critique of the hegemonic West’. In fact, Santos argues that Westerners in the Occident have used Occidentalism as a double image to Orientalism to castigate hegemonic Eurocentrism and Western values, exceptionalism, uniqueness and superiority, in the same way that Easterners in the Orient have applied it as a counter-image of Orientalism to criticise the West.42 He believes Occidentalism, as a double image of Orientalism, has been ignored or sidelined in the West because it did not ‘fit the political objectives of capitalism and colonialism at the roots of Western modernity’.43

The use of Occidentalism as a counter to Western colonialism and hegemonism has also been stressed by Ning. She describes Occidentalism as a ‘decolonising’ and ‘anti-colonialist’ strategy and a challenge to ‘those We...