![]()

Part I

Spectacular Histories, Spectacular Technologies

![]()

1

Television comes to town: The spectacle of television at the mid-twentieth-century exhibition and beyond

When a group of journalists visited Fleet Street on 6 October 1936 as guests of the Marconiphone Company, several weeks before the BBC began its regular broadcasts of television, they were treated to the following demonstration:

On a screen that was about ten inches by eight inches we saw in a sepia tone a moving picture which was quite as clear in definition as any home kinema […] First we saw the Alexandra Park grounds with people walking about little knowing that they were being televised […] We toured by television an exhibition that was to open the next day in the palace. We saw Leonard Henry doing comic Shakespearean acts – in a gas mask! This was close-up and had very definite entertainment value. We saw a mannequin parade, dancing, a band, [and] announcers.

(May, 1936)

Here we see television in Britain as spectacular from its outset. This pre-broadcast demonstration, combining an outside broadcast which transformed Alexandra Park and its unknowing visitors into pure spectacle (an image to be looked at without a clear narrative function) alongside various variety acts delivering the kind of performances (vaudeville humour, dance, band music and a fashion show) which would be collectively grouped under the generic title of the ‘spectacular’ show well into the 1960s at the BBC, presents television as a spectacular medium, dwelling on what it can show rather than what it can say. That this demonstration included a tour of an exhibition which was to take place in Alexandra Palace1 is also significant, given that the mid-century exhibition was to become such an important site in the history of British television. The exhibition was a site for the demonstration of television, a place in which (often spectacular) television would be produced, and a space where the significance and placement of television in the home would be deliberated. This chapter is thus interested in the ways in which television was presented as a medium of spectacle at the exhibition and was figured as a significant part of the spectacle of modernity in mid-twentieth-century Britain.

For many people in Britain, events such as Radiolympia (later the National Radio Show, 1926–64), the Ideal Home Exhibition (later the Ideal Home Show, 1908–) or the Festival of Britain (1951) would be the place where they would first encounter television, or first encounter new developments in television technology. For example, whilst Brian Winston asserts that ‘barely 2,000 sets’ were sold in the first year of television broadcast in the UK (1998: 112), it was reported in the Ideal Home magazine in November 1937 that a further 5,000 people had seen television in the past year at ‘Radiolympia, or the Science Museum at Kensington, or in a shop or a friend’s home’ (Anon., 1937) making the exhibition a key location for first encounters with television. The mid-century exhibition is thus an important, and largely overlooked, site in the history of British television, as it is in the US and beyond,2 in the narrative about the introduction of the medium to the public. This was a series of exhibitions that combined set manufacturers demonstrating their latest models and the ways in which they should be placed into a series of ‘ideal homes’, with exhibits made by or for the BBC (and later the ITV companies) in order to reflect on their technical, artistic and public service achievements. This chapter reveals that the large-scale public exhibition played a vital role in the early negotiation of the ontological status of television: what it was or is, what it would be, what it offered for a particular group or groups of viewers. This is why the history of television at the exhibition is of broader interest to cultural and media historians. Just as Anna McCarthy’s work on television in a variety of public spaces has explored the medium’s ‘ability to collapse distinctions between public and private space’ (2001: 32), illuminating a historically situated notion of medium specificity, so this chapter examines the ways in which often competing ideas about television’s medium specificity in the mid-twentieth century were exposed at the exhibition. It also takes its lead from William Boddy’s work on the launching of television and other media in the US (2004), in that particular attention is paid to what promotional strategies can tell us about industrial, institutional and popular understandings of what a medium is and what it can do. Whereas McCarthy’s exploration of ‘ambient television’ sought to understand the quotidian geography of television in public spaces, this chapter historicises what might be termed the ‘spectacular geography’ of public television, and, at its conclusion, offers some consideration of more recent events and spaces where television has been placed at the boundaries of broadcast, exhibition and live performance. In attending to the history of television at the mid-century exhibition, the origins of the conception of television as a medium of spectacle are revealed. An account of the appearance of television at the Festival of Britain, offering a case study of the ways in which television was figured at the mid-twentieth century exhibition, is thus an appropriate starting point.

The Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain, encompassing seven large government-sponsored exhibitions and the Battersea Pleasure Gardens, took place around the UK between May and September in 1951. It was conceived of as a wide-ranging celebration of Britain’s contribution to science, technology, industrial design, architecture and the arts on the centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851, and as a way to stimulate (or simulate) national recovery in the aftermath of World War II. The central exhibition at London’s South Bank offered a sense of celebration and liberation, a new-found freedom centring on a nation moving out of a period of deprivation and towards one of increased leisure and consumer opportunities. This part of the exhibition featured the futuristic architectural designs of the Skylon structure and the Dome of Discovery, transforming the South Bank into a site of wonder. In all exhibits, histories of past accomplishments were interwoven with narratives of a promising future for the nation. Discussing the appearance of the festival in family photograph albums, Harriet Atkinson describes ‘images of emancipation, of a populace reconnecting with itself after severe and extended privation, of people, many still in demob clothes […] enjoying their first day out in years’ (2012: 3).

The bringing together of science, commerce and the arts in the South Bank was stated and restated throughout the Festival and in the rhetoric that surrounded it. For example, in his speech to close the ceremony, the Archbishop of Canterbury said

The Festival, like the Dome of Discovery itself, was marked by imagination and ingenuity; a fearless gaze both into the vastness of space and into the minute details of every art and science; a pride in what Britain has achieved in things spiritual, cultural, scientific and industrial; a sense of what honest work and cooperation can do.

(Fisher, 1951)

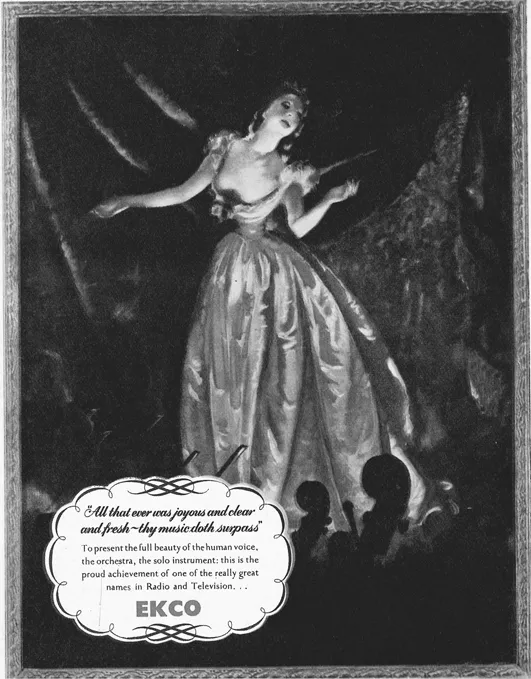

This rhetoric, in which science, arts and commerce are combined to spectacular effect, was also to be found in the promotion of television at the Festival, given that, as Sarah Street has argued, ‘The celebration of scientific achievement […] was presented as part of an exciting longue durée from Newton and Darwin to televisions, jet engines and radar’ (2012: 84). An advertisement for Cossor Electronics (Fig. 1.1) in the festival catalogue claimed television as a prime example of British scientific achievement: ‘Radio and Television […] are typical of the vast resources of Cossor experience and ingenuity, a great British national asset today – and in the future development of this electronic era’ (Cox, 1951: xix). However, in an Ekco ad placed several pages ahead (Fig. 1.2), television is lauded as a medium of the arts. This advertisement, bordered by a gilt picture frame, shows a painted image of a diva in lavish gold ball gown, as if lit from below. The accompanying text, reworking Shelley’s ‘To the Skylark’ (1820) reads:

All that ever was joyous and clear and fresh – thy music does surpass: To present the full beauty of the human voice, the orchestra, the solo instrument: this is the proud achievement of one of the really great names in Radio and Television […] Ekco.

(Cox, 1951: xxviii)

These two advertisements thus succinctly encapsulate television’s placement at the centre of the Festival of Britain’s dual aims to celebrate the scientific and cultural achievements of Britain.

Discussing the long-running Ideal Home Exhibition’s early days in the first half of the twentieth century, cultural historian Judy Giles argues that the exhibition

has to be seen in the context of an increased emphasis on visual display and spectacle that is characteristic of modernity […] Retail exhibitions were seen not only as venues to promote ‘the retail sale to the general public of novel and popular commodities’ but also as opportunities to display, often spectacularly, the products of science and technology.

(2004: 110)

The spectacle of modernity was to be seen in almost every element of the Festival of Britain, and, in line with this, many of the BBC programmes broadcast from the Festival, produced by the Corporation’s Outside Broadcast Unit, stressed this in their design. For example, the series Festival Close-Up (1951) produced episodes such as ‘Adventure in Architecture’ (tx. 7/5/51), which focused on a series of slow pans up and across Skylon, the Radar Tower, Observation Tower, Lion and Unicorn and so on,3 and ‘Experiment in Design’ (tx. 21/5/51), in which the designs of the Festival Pattern group were shown in great detail and lingering close-up. In the latter, the ‘Haemoglobin’ pattern produced by the Festival Pattern group was shown by cross-cutting between a silk scarf and an extreme close-up of a plate containing the presenter Patricia Laffan’s meat ration as she explained ‘Perhaps I better say that the colours are – well somewhat violently gay – atomically gay even’ (BBC, 1951a).

The special programme The Lights of London (tx. 16/7/51) epitomised the Outside Broadcast Unit’s presentation of the spectacle of modernity at the Festival. In the billing produced for the Programme Planning Department, Keith Rogers of the Unit, eloquently describes the programme:

The Festival Lights bordering the Thames between Westminster and Blackfriars provide an unforgettable sight. Tonight, a visit is made to the South Bank at dusk to watch the scene as floodlit buildings assume a new beauty and the hardness of concrete and steel is softened or lost in the lace patterning of thousands of lights.

(Rogers, 1951)

A similarly poetic description of The Lights of London was provided in a later press release:

On Wednesday the television cameras are attempting to capture the magic of the scene as concrete and steel, and the stately utility of London’s buildings, together with the inevitable untidiness and litter of a great exhibition fade with the twilight, to be replaced by pools of light rippling in the river, by the flashing fountains and the soft, almost ethereal, beauty of floodlit stone.4

The lyricism of this programme, with its languorous pans5 over the South Bank at dusk, was underscored by a romantic orchestral soundtrack which included the Melanchrino Strings’ ‘Portrait of a Lady’, Peter Yorke’s ‘Dawn Fantasy’ and Easthope Martin’s ‘Evensong’.6 During the period of the Festival then, outside broadcasts concentrated on emphasising the spectacular nature of the Festival and its associated architecture and imagery, alongside coverage of the pomp of the opening and closing ceremonies, and a special five-month season of broadcasting including ‘a season of Festival Theatre […] a series on the history of British entertainment in the twentieth century and a cookery series [which] featured regional British cooking’ (Easen, 2003: 61).

In addition to these programmes that concentrated on the visual elements of the Festival of Britain, the two main television exhibits, the ‘Television’ pavilion and the adjoining ‘Telekinema’7 in the ‘Downstream’ section of the South Bank exhibition, were also designed to reflect on and demonstrate the spectacle of modernity. The former (Fig. 1.3) was a two-story building designed by Wells Coates intended to ‘tell the whole story of broadcasting from the beginning’ (Bishop, 1949). Malcolm Baker Smith, who wrote the treatment for the pavilion and supervised its content, was instructed by the BBC’s Controller of Television, Norman Collins, to produce

a broad, popular, historical treatment of Television from Baird days up to the present, with a peep into the foreseeable future, always remembering that everything in the script must be illustratable in terms of an object which can be placed on exhibition.

(Collins, 1950)

The Television pavilion was fronted by an eye-catching ‘shop window’ containing a 14 foot by 8 foot ‘penumbrascope’,8 on which was seen ‘in constant motion and with a constant change of colours, the word “TELEVISION”, together with stylised shapes representing the three main components of television – Light, Vision and Sound’ (Baker Smith, 1950: 3).9 Four large framed panels were added to the outside of the building just before opening with ‘“blow ups” of selected photographs of TV productions – “star” productions – to be permane...