![]()

CHAPTER 1

DEVELOPMENT SYNERGIES

Decentralization and Participation: Conceptualizing their Linkages

The conceptual framework developed in this chapter is a crucial first step towards building the overall argument in this book – namely, that the potential for (local level) synergies between decentralization reforms and participatory approaches to rural development in Morocco is currently still limited. This chapter provides the conceptual basis to understanding how several overarching goals are actually shared by decentralization reforms and (certain types of) participatory approaches, and how paying more attention to potential synergies can lead to more effective development outcomes.

At the theoretical level, the term “synergies” refers to positive interaction effects between the two approaches to development, and between political and social forms of participation in particular. These synergies in turn have the potential to achieve social transformations that help to realize certain development objectives more efficiently, effectively, and with a more sustainable impact than these approaches would have if implemented in isolation. These objectives include empowerment, improved service delivery, and administrative autonomy along with greater downward accountability, partnerships, and enhanced local organizational and human capacity.1 At the practical level, local government and local community-based organizations (CBOs) can be considered proxies for decentralization reforms and participatory approaches respectively, and the term “synergies” at this level refers to “mutually reinforcing relations between governments and groups of engaged citizens”.2

In terms of its theoretical perspective, this study is situated in the literature on “participatory local governance”, which originates in post-Marxism and argues in favor of radical, transformative development and democracy that involve changing power relations.3 This perspective should be distinguished from the revised neo-liberal position taken up by researchers at the World Bank,4 which remains essentially technocratic in nature.5 For example, McLean et al. advocate working within “the opportunity space”.6 This “refers to the range of possibilities offered by the enabling environment, without efforts to alter the fundamental structures of a society or relevant institutions”. As Mohan and Stokke point out,7 this implies that the empowerment of the powerless could be achieved within the existing social order without any significant negative effects upon the power of the powerful. While I disagree with this view, I believe that the analytical tools developed within the “technocratic” perspective can still be useful in examining the potential for social transformation in contexts in which conditions for decentralization/participation synergies are mostly still lacking, as is the case in Morocco.

This chapter is structured as follows. This section considers the conceptual implications of the literature review provided in the preceding chapter. The next section presents the conceptual framework on local government–CBO synergies at the local level. The final section introduces the criteria for assessing internal and interactive capacity with regard to local government and CBOs respectively.

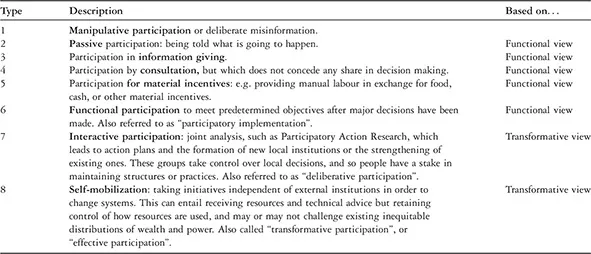

In the Introduction, the distinction between “political” forms of participation (as promoted by democratic decentralization) and “social” forms of participation (as promoted by participatory approaches) was introduced. “Social” forms of participation can be divided further into those that are based on an “instrumental” (or functional) view (which holds that participation is a methodology resulting in more cost-efficient and effective projects) and those that try to implement a “transformative” view (i.e. based on the belief that true development lies in strengthening people's ability to improve the economic and social conditions of their lives as well as to change the power structures that hinder them in doing so). In fact, as Table 1.1 shows, it is possible to identify several types of participation within these two views.

Table 1.1 A typology of participation

Source: J. Drydyk, “When is development more democratic?”, Journal of Human Development, 6(2) (2005), pp. 259–60, citing J. Gaventa, “The scaling-up and institutionalizing of PRA: Lessons and challenges”, in J. Blackburn and Holland (eds), Who changes? Institutionalizing participation in development (London: Intermediate Technology Publications, 1998) pp. 153–66 and J. Pretty, “Alternative systems of enquiry for sustainable agriculture”, IDS Bulletin, 25(2) (1994), pp. 37–48; and D. A. Crocker, “Deliberative participation in local development”, presented at International Conference of the Human Development and Capability Association, 29 August–1 September 2006, Groningen, Netherlands, pp. 2–3.

This discussion builds on the work of Williams, who calls for a more explicit political analysis of the impact of participation. The question is ultimately, in Williams' words, “what longer-term political value do participatory processes have for the poor?”.8 As Moore and Putzel argue, an important criterion for the success of development projects should be the degree to which they contribute to the mobilization and sustained political action of the poor.9 This discussion links social forms of participation in (rural) development projects to political forms of participation that successful democratic decentralization (at least in theory) both requires and strengthens. This in turn leads to the question of how, and to what extent, participatory approaches can interact with decentralization in ways that would strengthen it.

These interactions can take place both at the individual level, i.e. the impact of participatory approaches on individual agency, and that of social structure, i.e. local governance arrangements and power relations.10 As for the first, the main question is, “to what extent can social participation enhance peoples' political participation?” This includes examining the impact on people's political capabilities. These consist of “self-confidence, capacity for community organization, recognition of dignity, and collective ideas” to (re-)negotiate political space.11

As for the level of social structure, the main questions to ask are, “to what degree do participatory programmes reshape political networks? How are existing roles of brokers and patrons challenged or reinforced?” (bearing in mind that the latter are not always and everywhere a negative force). More fundamentally, do new spaces of participation ultimately challenge existing power relationships, and “equalize” social and economic inequalities? Or, in Sen's terms, do they contribute to development as freedom?12

This study addresses these questions by assessing the characteristics of such new spaces of participation, i.e. CBOs, and their interactions with the local governance structure. As John Gaventa argues,13 the transformative potential of “participatory” spaces must always be assessed in relationship to the other spaces that surround them, as new spaces might simply be captured by the already-empowered elite if other participatory spaces that serve to provide and sustain countervailing power are absent.14

However, even though the focus of this book is on governance arrangements at the local level, it is important not to view “the local” in isolation from broader economic and political structures, as Mohan and Stokke argue.15 I agree with Helling et al.,16 who suggest that local governance arrangements and, ultimately, local development impacts are determined by the wider (non-local) policy and institutional environment, which includes laws; central and sectoral government policies (accompanied by capacity enhancement and resource transfers); and values, norms, and social practices that influence people's decisions and behavior (such as propensity for solidarity, acceptance of social hierarchy, and relations with authority and leadership).

It is also clear that the dynamics of state–society relationships in any given country influence change at the local level to some extent. The works by political sociologists such as Williams (2004) and Heller (2001) point to the importance of political leadership in pushing a transformative political agenda,17 which often explicitly underpins the effectiveness of both participatory approaches and democratic decentralization. Each of the successful examples in the literature (such as Kerala in India, and Porto Alegre in Brazil) benefited from a sense of political direction and aimed to produce a fuller and more active sense of citizenship. This includes strengthening political capabilities, and opening up the State to effective public scrutiny.

Such initiatives require a high degree of state capacity to coordinate between levels of government, and to call for more regulation to guarantee basic transparency, accountability, and representation. In other words, a champion, or “reformist”, is required who pushes decentralization. In Heller's cases, these were organized political forces, and specifically left-of-center political parties that have strong social movement characteristics. These political parties are programmatic and ideologically cohesive with significant ties to grassroots organizations. These ties are required in order to shift powers, devolve funds, and promulgate laws and regulations. Most importantly, they are needed to circumvent or neutralize groups opposed to decentralization by challenging entrenched powers of patronage and bureaucratic fiefdoms, and for redirecting development resources from rents to development.

These initiatives were linked to the reshaping of political networks in which pro-poor alliances were not limited to the poor themselves, but extended beyond the grassroots to include cross-class and cross-institutional linkages (within government, NGOs and/or parties). Heller argues that civil society and social movements can play a critical role in shifting power from traditional party brokers to more grassroots factions.18 This opens up the opportunity for functional complementarities to emerge between political parties and social movements that allow them to become agents of democratic transformation.19 Finally, successful democratic decentralization often relies on the poor taking these programs and movements seriously and participating in them in big numbers because they offer the hope of significant change.

While these factors, present in a few “success stories” and in particular contexts, cannot be generalized and framed as binding conditions, they are nevertheless useful in organizing the material in the next chapter with regard to the Moroccan context. They point to first, the need to critically, and historically, examine the main drivers of decentralization reforms, and their underlying motivations. Second, it is useful to consider the nature and strength of civil and political societies at the national level, and the history of their relationships with the State. Finally, we cannot understand the current dynamics at the local level without first reviewing the nature and extent of popular participation in decentralization reforms, civil society movements, and participatory rural development programs in its historical perspective.

Local Government–CBO Synergies: Types of Interactions

Having set out the conceptual linkages between decentralization and participation in more detail, I now turn to a discussion of the different types of local government–CBO interactions. I argue that these possible types of synergies lie on a continuum of increasingly blurred state–society boundaries. Following Evans,20 I define synergy in this context as “mutually reinforcing relations between governments and groups of engaged citizens”. Before discussing the different degrees or types of synergies however, it should be noted that situations in which synergies are altogether absent seem much more common so far.

As indicated in the previous chapter, there is a growing literature presenting evidence that participatory methods often obstruct the potential benefits of democratic decentralization when they are used to establish a plethora of local institutions such as CBOs and village development or user committees. For example, Manor argues that the creation of user committees (as part of participatory approaches) fragments popular political participation.21 I also mentioned the example of World Bank support to CBOs, which frequently results in the creation of structures outside of local government. This can negatively affect the capacity of local government to support sustainable service delivery.

The underlying reasons for such lack of synergies, or “negative interaction effects”, can be found in differing professional and organizational perspectives and ideologies, institutional rigidity, and inadequate coordination among the actors involved.22 Issues of sequencing have also rarely been explicitly addressed, e.g. whether communities should be strengthened first, and then local governments, or both simultaneously.23 In short, the argument here is that the absence of synergies between participatory approaches and decentralization reforms should be considered as a serious obstacle to achieving local development.

Moving on now to positive interaction effects, Evans distinguishes between two elements that constitute synergy: complementarity and embeddedness.24 Complementarity suggests a clear division of labor, based on the contrasting properties (comparative advantages) of public and private institutions. Putting the two kinds of inputs together results in greater output than either public or private sectors could deliver on their own. For example, the State is responsible for ensuring the rule of law, which strengthens the efficiency of local organizations and institutions.25 A more tangible example is state provision of large infrastructure and citizen's contribution of local knowledge and experience that would be too costly for outsiders to acquire. These examples still fit nicely within existing paradigms in public administration, and do not force any rethinking of the public–private divide. However, complementarity can also promote social-capital formation in civil society.26 In the irrigation sector, for example, efficient (public) provision of the tangible facilities may have the intangible consequence of making it more worthwhile for farmers to organize themselves. In such cases, complementarity supports day-to-day interaction between public officials and communities. Indeed, further evidence suggests that the permeability of public...