![]()

We look at India from the outside

- a first phase in the cycle.1

Nasreen Mohamedi in her diary, Delhi, 1970

Prelude: Satori!

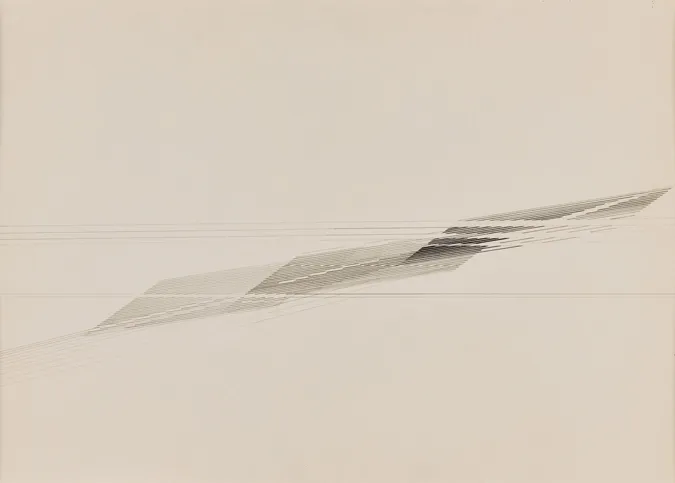

An ink line is traced across the toothed grain of the paper. Then another, and yet another, until a cluster emerges (Figure 1.1). From light to deepest grey, Nasreen Mohamedi’s untitled graph displays lines that are calibrated in tone, thickness and reach. The variations of tonal densities make for a curious rise and fall of light and shade; row upon row they create a hypnotic rhythm of their own. The methodical repetition of lines recalls the Persian calligraphic practice mashq, a visual discipline conducive to mystical revelation.2

For Mohamedi even the plainest of things – a leaf, a spider’s web, a dissipating cloud – could encourage revelation. ‘Satori!’ she would suddenly utter to her puzzled students. One of her more intimate Baroda pupils, the Parsee artist Nina Sabnani, remarked: ‘We did not always understand what she said but believed her anyway.’3 The Zen satori eludes the grasp of language, definition or description.4 Untranslatable, it implies an opening into the void, a kind of mental catastrophe, yielding the experience of tathata, which is wholeness, or the reality preceding conceptualisation.5 Satori breaks with the common view that tames an event by making it ‘enter into a causality, a generality, which reduces the incomparable to the comparable.’6 For the existentialist writer Albert Camus, moments of redemptive gnosis occur when the security operations that protect us from the terrifying intensity of reality fall apart.7 Revelation takes place at a moment of crisis. Random and unexpected, the revelatory experience lifts the individual out of chronos (profane time) into kairos (sacred time); this moment in its ‘pure status of exception’ and ‘power of mutation’ is the satori.8 Perhaps it is possible that revelation occurs when fleeing repression and terror; perhaps revelation could offer an escape from time, leading one to another ‘greater life’ as Camus put it.9

Introduction

Confronted with two world wars and the Nazi Holocaust, many European modernist thinkers addressed issues of historical memory and trauma in relation to visual representation, particularly abstraction.11 Lyotard, who grappled with both the Holocaust and the problem of representation, suggested that traumatic memories inevitably return only as experience, not as discursive memory – for there can be no memory without meaning, and the experience of extreme violence denies all meaning. Trauma cannot be represented but only ‘made present’ through the absence of meaning.12 Placed side by side with the event, the abstract work could neither be subsumed under existing modes of encounter or interpretation nor interpreted as a conscious response to an event.13

Although the horror of the Holocaust is recognised as a limit case in European and American scholarship, historian Gyanendra Pandey has suggested that the 1947 Partition of India is even more inexplicable.14 Partition, indeed, did not involve industrialised slaughter commanded by the state from a distance, but rather ‘hand-to-hand, face-to-face destruction’, a genocidal, ethnic violence frequently involving ‘neighbour against neighbour.’15 To recuperate Partition, as the underside of independence, remains a deeply contested task.

Drawn on the basis of contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims, the Partition line marked the emergence of two sovereign nation states: a Hindu-dominated but constitutionally secular India, and a Muslim Pakistan, its two wings separated by 1,000 miles of Indian territory.16 Over the course of a few weeks, an estimated 25 million refugees crossed the ‘shadow lines’ separating the two nation states: Hindus and Sikhs from areas designated as Pakistan migrated to India, while many Muslims migrated to Pakistan. One million people are reckoned to have died in the catastrophic transfer of power from colonial to national rule.17 Many factors contributed to the devastation of Partition, not least the hasty withdrawal of British colonial representatives – and the calculating ambitions of Indian leaders seeking to capitalise on the hurriedly negotiated settlement.18 (‘I fucked it up’ was Lord Louis Mountbatten’s own evaluation of his role in overseeing the division.)19

Formed out of colonial structures of governance, the governments of India and Pakistan sought to establish legitimacy and respond to the emergency of Partition. The two nations set up parallel Emergency Committees of the Cabinet to bring law and order to the ravaged region of the Punjab and the city of Delhi, and to manage the displaced millions.20 The reality of decolonisation on both sides of the divide meant that sovereignty would be exercised by regulating movements across their highly networked boundaries: bureaucratic and juridical regimes were deployed to deal with the paradoxes and contestations of residence, property and citizenship and to establish the correct national affiliation of refugees. The ongoing displacements, regulated by technologies devised to fabricate citizenship and mark ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, compel us to stretch our understanding of the process of Partition. ‘The figure of the “refugee” emerged to carry the scripted and rescripted labour of postcolonial governmentality.’21 Partition and Independence would determine the meaning of ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ in a national sense for Indian society and politics. As members of a minority, Muslims who stayed in India constituted ten per cent of the population of the newly independent nation. Considered a traitor to the holy cause of Islam by the founders of Pakistan, the ‘Indian Muslim’ was a living contradiction. Meanwhile in India, those Muslims who had chosen to remain had to demonstrate their loyalty in order to become naturalised citizens, notwithstanding the guarantee of equality extended by the Republic to all citizens, irrespective of religious affiliation.22

Through a series of related themes, this chapter explores in circular fashion the life and abstract work of Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–90). Born into a wealthy trading family in the bustling port of Karachi (then part of India), Mohamedi was raised in the cosmopolitan milieu of Bombay in the years following Partition.23 Her family belonged to the Tyabji clan of the Shiite Muslim community of Sulaymani Bohras, whose major fraternities developed over the centuries in the Indian trading centres of Karachi, Bombay, Baroda and Hyderabad.24 Like other West Coast Muslims, the Tyabji clan members were proud of their Arabic ancestry, as reflected in their choice of names and scholarship.25 Modernist in faith and practice, they actively supported the nationalist cause (the majority of Muslim communities had largely refrained from participating in the struggle for independence), staunchly believing in the future of an undivided, secular, and independent India.26 Among the first Muslim communities to ban purdah, a practice seen to limit intellectual development,27 the Tyabjis promoted mass education and literacy – in particular for women, who had hitherto been assigned the exclusive role of familial custodians and keepers of tradition. Elite Sulaymanis often encouraged their daughters to pursue education in English schools abroad, after completing their instruction in Urdu and other languages at home.28

Around 1913, Mohamedi’s father established in Bahrain one of the first trading companies dealing in Japanese photographic equipment, the eponymous Ashraf. As business flourished over the years, the company expanded across the entire Persian Gulf. A devout Muslim, Ashraf Mohamedi was keen to educate his daughters, but pressing business commitments caused him to delegate their education to his wife, Zainab. Urdu, Arabic, Persian and calligraphy were taught in the home, while educational grounding in English, French, mathematics and science took place at English schools.

Following the death of her mother in 1942, an event described ...