![]()

CHAPTER 1

LANDSCAPE AND CIVIC AUTHORITIES IN LATE ANTIQUE CORINTH

The history of the city of Corinth in all eras unfolded in the activities of people enhancing and exploiting the resources of the natural landscape of the Corinthia, shaping it through construction and cultivation, receiving ships or travelers at the Isthmus, rebuilding after earthquakes, and withdrawing to Acrocorinth in times of trouble. Corinthians, visitors and immigrants all contributed to this process, and so to history, but civic authorities in control of resources shaped the city in the most monumental way, and appear most prominently in the historical record. These included (mostly male and wealthy) local archontes (leaders), landowners, councillors of the colonial City Council, priests of the traditional Greco-Roman (or Imperial) cults, the Governor of Achaia, his staff and many other imperial officials. From the fourth century, the newly legal and increasingly powerful Christian archbishop of Corinth and his clergy increasingly overlapped with the local archontes, and took up some of their responsibilites around the city, while also overturning many traditional areas of civic patronage.

The Landscape of Late Antique Corinth

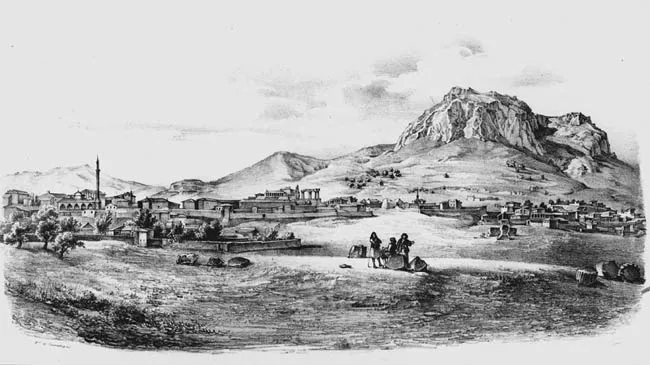

Corinthian history is intertwined with the natural topography, geology, climate, resources, opportunities and limitations of the landscape of the Corinthia, the territory of the city of Corinth. Geographers, generals and poets alike have long admired the Corinthian landscape, with the city center commanding two seas, the narrow Isthmus of land in between, and a fertile coastal plain below the natural crag of Acrocorinth (see Figures 1–10, 1.1–1.5).1 Natural springs, stones, earthquakes, rainfall, flora and fauna all still shape the possibilities and limitations of urban life today, as in millennia past, in the Corinthia, the territory of the city of Corinth, at the northeastern corner of the Peloponnesian peninsula.2 Here, the Isthmus forms a natural landbridge between the Peloponnese and central Greece, dividing the Corinthian Gulf on the west from the Saronic Gulf to the east.3 North of the Isthmus, the Geraneia mountains and Perachora (or Peraea) peninsula stab westwards into the Corinthian Gulf, forming the border with Megara, today part of Attica.4 To the south, Mt. Kyllene's foothills step down from the west at Mt Apesas (Phokas) and then curl around to the east to cradle the Corinthian plain, reaching the Saronic Gulf at Mt Oneion and its eastern hill Stanotopi, with steeper peaks and mountain valleys just to its south, including Solygeia (modern Galataki), Sophiko and coastal Korphos (probably the ancient Speiraion cape and harbor).5 This mountain range divides Corinthia from Arcadia, Argolis and then Epidauria to the south, with their upland valleys and the ancient cities of Phlius (Agios Georgios, Modern Nemea), Kleonai (Agios Nikolaos, near the Nemean festival site at Ancient Nemea) and coastal Epidauros (the city was on the north coast below Epidauros' more famous Sanctuary of Asklepios).

Figure 1.1 Ancient Corinth and Acrocorinth, looking south from Lechaion in 1810, with columns of Temple of Apollo at center, panorama by Von Stackelberg. (published in Williams 1829, vol. 1, pl. 9.)

To the west, the deep gorges of the seasonal torrents of the Longopotamos (Rachiani) and then Nemea (Koutsomadiou or Zapantis) Rivers separate Corinthia from ancient Sikyonia (ancient Sikyon is modern Vasiliko, with its harbor Kiato), the Asopos (modern Agiorgitikos) River valley, and then the narrow coastal plain of Achaia, with its “ever changing mixture of bold promontory, gentle slope, and cultivated level … crowned on every side by lofty mountains,” which Colonel Leake once praised.6 At the heart of the Corinthia, the natural bastion of Acrocorinth rises up above a skirt of rocky terraces descending unevenly to the coastal plains below, cut off from Mt Oneion by the Leukon (Xerias River) valley to the east.7 The Corinthia thus has two seashores as natural boundaries, permeable sites for sailing in or out, to west or east, but also more solid southern and northern mountain boundaries, where civic, military and later ecclesiastical circles of authority radiating out from the Bouleuterion (Council House), fortress or cathedral extended along narrow roads to neighboring cities.

Figure 1.2 Ancient Corinth and Acrocorinth, looking south from Lechaion in 2017. (Photo by author.)

Today, the village of Ancient Corinth occupies the city center of ancient Corinth, sitting on raised terraces north of Acrocorinth with a panoramic view of the Gulf of Corinth, the Isthmus, and the proverbially fertile coastal plain, the Vocha, which extends west towards ancient Sikyonia, and northeast as far as modern Corinth on the coast of the Isthmus (Figures 2–3, 1.2–1.3).8 Modern Corinth, Korinthos, is now the political, economic and ecclesiastical city center of the Corinthia, but it was founded only after an 1858 earthquake, and sited on the west side of the Isthmus between two ancient ports, Poseidonia and Lechaion. Lechaion has been identified by visible ruins, mounds of dredged sand, and a shallow artificial lagoon marking the man-made harbor which once served the Corinthian Gulf, the Ionian and Adriatic Seas, and the Western Mediterranean.9 On the eastern side of the Isthmus, Kenchreai (modern Kenchries), south of Poseidon's Sanctuary at Isthmia, was the main port in Late Antiquity for accessing the Saronic Gulf, the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean (Figure 10).10 The modern Corinth Canal was cut across the narrowest point of the Isthmus, alongside the ancient roadways and fortification walls which once ran from the western harbor of Poseidonia (modern Corinth) to Schoinous (modern Kalamaki), the ancient port of Isthmia, on the east side of the Isthmus.

Geologically, the Corinthia, like most of Greece, is a skeleton of hard limestone mountains under a body of former seabeds, with a skin of recently deposited coastal sediments. Acrocorinth is ringed with layers of uplifted and tilted former seabeds: soft limestones, conglomerates and corals overlying even softer marls, resources extracted since Antiquity (but not including any marble).11 Corinthian limestone was quarried directly from the surface, notably from the fossilized sand dunes of oolithic limestone which run through the ancient city center and to the east.12 At the edges of these limestone and conglomerate terraces, the underlying marl layers yield clays for the famous Corinthian ceramics.13 These layers are also relatively impervious to water, and thus channel groundwater out along the northern edges of the terraces to form east-west bands of natural springs. The use of these natural springs by the ancient Corinthians has been well studied: atop Acrocorinth, along its northern base, and along the northern edges of the upper and lower terraces of the ancient city, some 24 springs emit cool, fresh water year-round.14

Medium-sized earthquakes (4 to 5) are very common in Poseidon's Corinthia, but only rarely do earthquakes do extensive damage, or generate tsunamis, uplift or subsidence. A series of segmented faults form the southern side of the Corinthian and Saronic Gulfs, part of the larger African-European plate boundary.15 Ambraseys claims no earthquake of the past 300 years in Central Greece has exceeded 7.5, and the 15–20 km. length of the faults probably makes this an upper limit for this region.16 Specific pre-modern earthquakes mentioned in texts or visible in the landscape are rarely precisely datable, and the types of tectonic activity common in the Corinthia must be carefully combined with any ancient account, or archaeology.17 Stephen Miller has pointed out that although the strong earthquakes of 1858 (7.0) and 1861 (7.3) caused extensive damage to houses in both Ancient Corinth and Ancient Nemea, the ancient columns still standing at both sites were unharmed. The Nemean temple's fallen columns, neatly splayed outwards, along with the flexibility of multi-drum columns, mean that the ancient destruction of the Temple of Zeus at Nemea was largely done by human hands, with implications for other colonnades throughout the Corinthia.18

No written account of a fourth-century earthquake specifically names Corinth. Libanius refers to earthquakes in 363 in Greece and Palestine in his Funeral Oration for the emperor Julian; his phrasing is echoed by the historian Zosimus, who describes an earthquake in Greece after the death of Valentinian on 17 November 375.19 In both cases, the topos is used of “every city in Greece but one was destroyed” after the death of an emperor. Rothaus thus suggests the second earthquake of 375/6 is a literary fabrication, though he does not cite the epigraphic evidence outlined below.20 Jerome, in a commentary on Isaiah, also recorded the 363 quake in Palestine, then made fuller reference to another quake of 21 July 365, affecting Sicily, many islands and the coast of Epirus.21 This is almost certainly the quake and tsunami which Ammianus dates in the second year of the joint reign of Valens and Valentinian (365/6), and which he says affected Alexandria, Sicily, Crete and the southwestern coasts of the Peloponnese and Epirus.22

Corroborating evidence for a late fourth-century earthquake affecting Corinth, and the interest of local officials in making repairs to public buildings afterwards, comes from an inscription built into a gate at Nauplion (the port of Argos), origin unknown, which honors a scholastikos (rhetorician, or advocate) for repairing “a basilica” under the emperor Valens (and Gratian?, 375–8?) damaged “by earthquakes and movement of the seas (tsunamis),” κατὰ σισμοὺς καὶ τοὺς θαλαττὶο[υς \ κατακλυσμοὺς?].23 The clearest archaeological evidence for late fourth-century earthquake damage at Corinth comes from the Great Bath on the Lechaion Road, repaired c.400, and the Governor of Achaia's restoration of colonnades in front of the West Shops and South Stoa under Valens and Valentinian (see Chapter 3). The southern harbor mole at Kenchreai was also probably shaken and sunk by seismic activity c.400 (see Chapter 7, and Figure 10). Thus, although Corinth is not explicitly mentioned in any literary source for a fourth-century earthquake, there is damage to public buildings at Corinth and repairs in the late fourth century which could be seismically motivated.

Figure 1.3 Ancient Corinth, the Corinthian Gulf & Perachora, looking north from the slopes of Acrocorinth in 2017. (Photo by author.)

In the sixth century, Malalas explicitly records that Corinth suffered an earthquake in 520/1, the third year of Justin's reign, when that emperor sent aid to the city, perhaps even making repairs to the Forum, where he was honored in an inscription.24 Procopius invokes earthquakes at Corinth twice for rhetorical value discussing the reign of Justin's nephew and successor Justinian. He uses them to give the negative side of Justinian's era of authority in the Secret History, enumerating the natural disasters which either Justinian caused as a demon incarnate, or which God caused as punishment for the Roman Empire from 518 to about 558/9.25 He emphasizes in particular the loss of life in Corinth and eight other cities, first victims of earthquake, and then the plague from 541/2 on. Corinth is significant enough to be listed last, a pendant to Antioch listed first. Procopius emphasizes the scale and range of diasters and “destruction of humanity,” not recovery, for a very long list of places. However, he also refers to earthquakes at Corinth while praising Justinian for building the Hexamilion Wall across the Isthmus in his Buildings.26 It is likely that he is referring first of all in the Secret History and the Buildings to the quake of 520/1, for which Malalas says the emperor Justin sent relief (see above). Procopius may also,...