Chapter 1

The Teacher of Germany

An author like Thomas Mann has made deeper strata of the German spirit and soul accessible to the world than any number of books that merely present experience or memory in formulaic fashion… . In the continuities that connect Thomas Mann to Nietzsche and Wagner, European intellectual circles get a clear sense for the continuity of German spiritual development.

—Max Rychner, “The Nobel Prize in Literature 1929”

Whenever I meet Thomas Mann, 3,000 years of tradition look down upon me.

—Bertolt Brecht, letter to Karl Korsch, July/August 1941

That Thomas Mann should at one point be celebrated in the United States as the leading voice of the “other Germany,” and as an intimate enemy of his native country’s official government, would have come as a surprise to many who read his works during the time of the First World War. In his exhaustive summation of his political views of the time, the paradoxically titled Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918), Mann argues that a true artist is obligated to refrain from any intervention in public affairs. He further describes this attitude as distinctively German and casts scorn on writers who try their hand at journalistic commentary, a stance he associates with French and English public life.

Twenty years later, these earlier remarks would occasionally still come to haunt him. In December of 1938, for example, the New York Herald Tribune published a letter to the editor that condemned America’s embrace of Mann as a spokesperson of the other Germany, and demanded, “Read his ‘Friedrick und die Grosse Koalition’ [sic]—there’s a copy in the New York Public Library—and observe the sea-change that has in recent years transmogrified his political theorizing.”1 The author of this letter, a certain Thomas A. Baggs, was poorly informed about Mann’s oeuvre in translation, for “Frederick and the Grand Coalition” was, in fact, the only one of the author’s patriotic wartime writings that had been translated. But the larger point stands. For example, Mann had written that Germany would inevitably win the war, because “history will not crown ignorance and error with victory” (GKFA, 15.1:45). Had ordinary Americans in the late 1930s been aware of such chauvinistic remarks, they would most likely have abandoned him.2 Mann himself was keenly aware of this, and made sure that Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man was never translated into English during his lifetime.

Viewed from a different perspective, however, Reflections actually foreshadows rather than negates Mann’s later role in America. For its very existence is premised on the assumption that an author and his country are conjoined by a representational link, and that both the words and the actions of an individual reflect the larger character of the national community. This assumption—or rather this active desire to become representative—guided Thomas Mann’s career from the very beginning and remained intact throughout his various reinventions and transmogrifications.

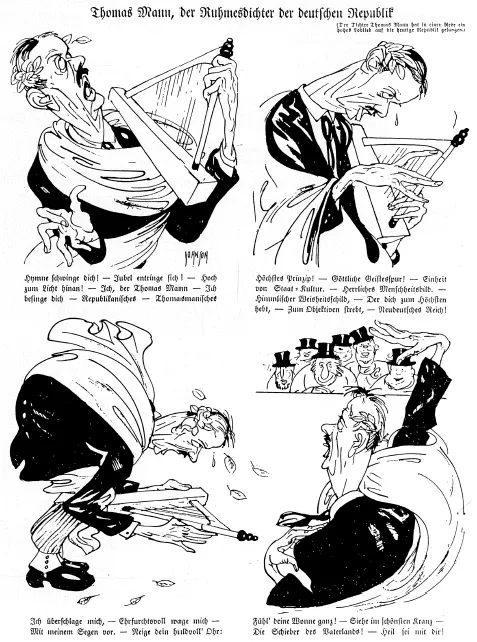

During the years of the Weimar Republic, Mann’s representative aspirations became the subject of much commentary and even more ridicule. As early as 1919, the conservative journalist Hanns Elster bestowed upon Mann the epithet “precaeptor Germaniae” (teacher of Germany), an honorific title that had first been applied to the Renaissance humanist Philipp Melanchthon and indicated an author who through his writings guided the nation to self-understanding.3 Conservative opinion cooled off considerably after Thomas Mann publicly embraced the Weimar constitution in 1922. A satirical drawing by the right-wing caricaturist Arthur Johnson relentlessly mocks him as panegyrist of the republic (figure 1.1). Liberal and left-wing opinion was often similarly scathing. The Austrian essayist Jean Améry, for example, wrote an amusing piece in which he spoofs the obeisance that Thomas Mann so often seemed to expect (and usually received) from the Weimar public by summarizing the breathless narration that a German radio reporter provided from the 1929 Nobel Prize awards ceremony: “Thomas Mann just arose from his seat, and now his figure, so accustomed to wearing a tailcoat [seine frackgewohnte Gestalt], is approaching the podium with bounding steps.”4

In reality, Thomas Mann wasn’t nearly as rigid and pretentious as his fiercest critics liked to suggest. His copious and often agonized reflections concerning his representative status reveal that he was instead intensely attuned to the social flux around him. And his later career in America demonstrates that he ultimately owed his fame to his ability not to resist, but rather to respond to, unprecedented historical conditions. Whatever else it might have been, Nazism was a powerful manifestation of modernity. In successfully positing himself as its antipode, Mann was not expressing blind obeisance to tradition but rather engaging in a dialectical dance that transformed the social role of the author into something that it had never been before.

Figure 1.1. Arthur Johnson, “Thomas Mann, Panegyrist of the German Republic,” Kladderadatsch, July 22, 1923, n.p.

Role Models and Literary Antecedents

The most obvious symptoms of Mann’s search for representational forms that would be suitable for his own era can be found, paradoxically, in his near-constant reflections upon the literary past. Mann’s numerous speeches and essays about his poetic forebears do not simply form an attempt to appropriate these figures as sources of authority. The outrage with which conservative circles greeted his 1933 lecture “The Suffering and Greatness of Richard Wagner” (in which Mann accuses Wagner of bourgeois pretentiousness and questions whether the idea of the “total work of art” is really as artistically profound as the composer’s disciples would argue) already demonstrates this.5 Mann’s critical reflections should instead be seen as attempts to better understand the present by analyzing both its similarities and its differences to the recent past.

One of the most important antecedents whom Mann used as a reference point in this process of historical self-triangulation was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Mann’s literary engagement with the older writer was multifaceted and encompassed such internally diverse projects as the story “A Weary Hour” (1905), the essays “Goethe and Tolstoi” (1923), “Goethe as a Representative of the Bourgeois Age” (1932), “Goethe’s Career as a Writer” (1933), “Goethe’s Faust” (1938), and “Goethe and Democracy” (1949), as well as the historical novel Lotte in Weimar (1939). Indeed, it is notable that with the exception of a single essay on Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (“Lessing,” 1929) and a few crucial remarks about Martin Luther, Mann never turned his gaze on any earlier figure in German literary history.

Goethe was not the first writer ever to be acclaimed as the archetypal spokesperson of the German cultural tradition. The example of Philipp Melanchthon has already been mentioned, and during the 1780s German readers celebrated the novelist Christoph Martin Wieland as their “classical national author.”6 Goethe, however, was the first person to outline a theory of artistic representativeness that took into consideration the extent to which authorial reputations are both created and continually undermined by social change. In his classic pronouncement on the subject, “Literary Sansculottism” (more commonly translated as “Response to a Literary Rabble-Rouser,” 1795), he argued that Germany would never be able to produce a truly “national” author because the country was “politically splintered despite representing a geographical unity” and lacked a “real cultural center where writers can gather and find a common guideline to aid their development.”7 Goethe also fretted about the increasing influence of a “mass public without taste.”8 In other words, he displayed a keen analytical understanding of the dawning age of nation-states, as well as of the constraints that govern artistic production in bourgeois societies, in which writers can no longer depend on the aristocratic patronage of the feudal court system. In the two essays that Mann wrote to commemorate the centenary of Goethe’s death, “Goethe as a Representative of the Bourgeois Age” and “Goethe’s Career as a Writer,” he took great care to emphasize this modernizing aspect of the great author’s legacy.

A second foundational rumination on representative authorship within the German tradition, Friedrich Schiller’s “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry,” was also published in 1795. Like Goethe, Schiller was a lifelong intellectual touchstone for Thomas Mann, who paid heartfelt tributes to his forebear in the story “A Weary Hour,” the abandoned essay manuscript “Intellect and Art” (1909–12), and the “Essay on Schiller” (1955), among others.9 As was the case with “Literary Sansculottism,” “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry” had been written in response to the trauma of the French Revolution. According to Schiller, the revolution reveals the fundamentally fragmented nature of modern societies. In such societies, artists will have to commit to one of two choices. They can either strive for an ideal depiction of their surroundings, treating the world as if it could somehow be made whole again, or they can adopt a reflective and critical attitude, acknowledging that they will invariably produce fragments. To artists choosing the former path, Schiller gives the name “poets” (Dichter); to those choosing the latter he refers as “writers” (Schriftsteller).10

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Germans began to self-identify as citizens of a “country of poets and thinkers” (Land der Dichter und Denker).11 The concept of the critical and reflective “writer” was instead associated with neighboring France and to a lesser extent also with Great Britain and the United States. In the early years of the twentieth century, as tensions between Germany and the western European nations intensified, it was joined by the more derogatory term “man of letters” (Literat), which referred to a professional scribbler or hack, somebody capable of adopting any viewpoint whatsoever as long as there was money to be made from it.12

The irony, of course, is that German society in the late nineteenth century was more fractious than it had been at any point in the country’s past. The second industrial revolution, set in motion by the dawn of the electrical and petrochemical ages, belatedly threw what had been a largely agrarian nation into a condition of modernity. And modern societies inevitably splinter into a number of discrepant groups—workers, capitalists, beleaguered farmers and artisans, bureaucrats, intellectuals—whose outlooks contradict one another as a consequence of the differing roles that they play in the social collective. Writers certainly do not escape this process. At the same time that popular sentiment in Germany thus enshrined the poet as a kind of oracular figure, the sole guarantor of a national identity that in real life seemed lost amid the squabbles of partisan interest groups, the people doing the actual writing were busy carving out a social niche for themselves that was as insular as any other.

In light of this gap between image and reality, it will be evident why Thomas Mann raised considerable hackles when, to mark the centenary of Goethe’s death, he pronounced him a prototypical “representative of the bourgeois age” and—even worse—spoke of his “career as a writer” (Laufbahn als Schriftsteller) rather than of his “calling as a poet.” Mann even explicitly stated that “it is a fruitless and futile mania of the critics to insist on a distinction between the poet and the writer—an impossible distinction, for the boundary between the two does not lie in the product of either, but rather in the personality of the artist himself” (ED, 44, translation modified; GW, 10:181–82). This was not an innocent pronouncement but rather a highly self-aware effort to enlist Goethe’s prestige as a quintessentially “German” artist for a reformed understanding of what might actually constitute such a representative function.

Mann’s inspiration for this process of redefinition was Friedrich Nietzsche, from whom he borrowed the term “insight” (Erkenntnis, a word that is sometimes also translated as “knowledge” or “understanding”) as the principal goal for which the modern writer should strive. In his first major aesthetic manifesto, the 1906 essay “Bilse and I,” for example, Mann wrote, “There is an intellectual school in Europe—Friedrich Nietzsche created it—which has accustomed us to combine the concept of the poet with that of the one who strives for insight. Within this school, the border between art and criticism has become much less definite than it used to be” (GKFA, 14.1:105–6). Four years later, in the unpublished essay “On the Social Position of the Writer in Germany,” he again asserted that the modern man of letters is “an artist of insight, separated from art in the naive and trusting sense by self-consciousness, intellect, moralism, and a critical disposition” (GKFA, 14.1:225). Intellectual activity and a moral sense here combine with self-consciousness to reinforce the image of an artist as someone who is painfully aware of living in a fragmented world, in which all viewpoints are inevitably subject to further disputation and critique.

This insistence on critical reflection and an awareness of things as they actually are was largely rooted in Mann’s lifelong respect for his forefathers, who rose to their prominent social position through bourgeois pragmatism and commercial calculation. Already in 1895, for example, he wrote a letter to his friend Otto Grautoff in which he placed the “writer with a strong intellectual talent” above the mere poet, but the businessman above both (GKFA, 21:58; emphasis in original). By contrast, Mann had very little patience for the conventional German understanding of the “poet” as a purveyor of idealized alternatives to reality, or of what in one of his notebooks he calls creations that “arise from Orphic depths with slurred speech” (GuK, 158). “No modern creative artist,” so he insisted, “can regard the critical faculty as something that is opposed to his inner nature” (GKFA, 14.1:86). Everything that he ever wrote about Goethe, Schiller, and indeed Wagner can consequently be read as an attempt to disentangle these figures from their traditional role in German intellectual life and recuperate them as forerunners of his own conception of the modern writer. This would prove to be a lifelong task, and the frustration is evident in Mann’s 1925 response to the conservative German professor Conrad Wandrey, who had sent him a manuscript once again extolling the virtues of the Germanic poet type: “What is certain is that this a difficult and almost always awkwardly executed opposition. You do know that Goethe, in contrast to Shakespeare, considered himself to be a writer, don’t you?” (GKFA, 23.1:136).

Artistic Habitus and the Contrast with Stefan George

Figuring out how to position himself in relationship to a...