![]()

CHAPTER 1

From Judah to Israel

Territory and Identity

The relationship between Jewish ethno-national identity and the geographical space inhabited by Jews was dynamic in antiquity; it was reflected in the conversion of the name “Judea” to “Israel” and in the shifts in the name of the territory, as well. The borders of the land, though fluid, were closely bound up with the identity of its residents; as the territory shifted, so, in a sense, did their identity.

In this chapter, we trace the changes in the names for both land and nation in the biblical and rabbinic periods,1 focusing on the relationship between space and identity from the Second Temple to the Byzantine period. We open with an analysis of the names of the land and nation in biblical literature and other sources from the period under discussion, including contemporary coins. We then trace the transformation of these names from Judah or Judea (Yehudah) to Israel (Yisrael), discussing evidence from the Great Revolt of 66–70 C.E. to the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–135 C.E., as well as the corollary shift in the name of its members from Jews (Yehudim) to members of the nation of Israel living in the land of Israel (Erets Yisrael). Particular attention is given to the use of both nomenclatures in rabbinic literature, and these texts are compared with previous compositions and archaeological artifacts.

The correspondence between the nation’s names, territory, and members at particular times in history reflects the link between the nation’s self-concept and its view of the geographical expanse it identified as its land. It was only later, in the modern period, that the name of a nation began to adhere to one side of these dichotomies while the name of the land and/or polity reflected the other.

JUDAH AND ISRAEL IN BIBLICAL LITERATURE

We begin by looking at the names for the community and the land in biblical literature. In Jewish scriptural sources, the primary name for the nation is Israel (Yisrael). The Pentateuch uses “Sons of Israel” (Bnei Yisrael, often translated as “Israelites”) to identify the people, referring to the biblical Jacob, also known as Israel. Exodus, for example, begins with “And these are the names of the Sons of Israel that went down to Egypt” (Ex 1:1), and the pharaoh compares the size of the “nation of the Sons of Israel” to that of his own (Ex 1:9). Yet upon returning to the land after slavery in Egypt and wandering in the desert, the congregation enters what is simply referred to as the land (ha’arets) or the land of Canaan (Erets Canaan), not the land of Israel (Erets Yisrael).2

“Judahite” (Yehudi) appears only in late biblical literature, mostly in the books of Jeremiah and Esther. This name refers to the inhabitants of the Southern Kingdom of Judah after the fall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 720 B.C.E. Seals and coins dating to the Persian period (ending with Alexander’s conquest of the land in 332 B.C.E.) identify the region according to the official name of the administrative province of the Persian Empire. Persian districts extended across what had formerly been the Kingdom of Judah, which in the Aramaic was rendered as Yehud (Judea).

In the books of Chronicles, which also date to the Persian period, the name “land of Israel” appears only four times; the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, from the same time, do not use the term for the land at all. The reason for this relates to the territorial significance of the term in Chronicles, where it refers to the entirety of both the Kingdom of Judah and the Kingdom of Israel.3 The author, who composed his text in the Persian province of Yehud, corresponding roughly to the territory of the defunct Kingdom of Judah, was primarily interested in historiography. He considered districts in what was once the Kingdom of Israel to his north as part of his own land, just as he considered the remnant of its population that had not gone into exile as part of his own nation.4

In contrast, the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which recount primarily the events of their time, are concerned only with the Persian province of Yehud. The Aramaic passages in Ezra describe the exiles returning from Babylon as Judeans (Yehudaia; see Ezr 4:12, 23; 5:1, 5; 6:7, 8, 14). However, when the authors discuss the people of the historical past, they employ the name “Israel.”5 Accordingly, the name Israel sometimes appears in the Hebrew Bible exclusively for the inhabitants of the Northern Kingdom, but at other times for both the Northern and Southern Kingdoms, depending on the time period the text addresses.6 Nonetheless, “Judah” and “Judeans” refer only to the Southern Kingdom and its people, never the Northern Kingdom and its people. In later periods, the terms Judah and Jews also signified the Persian province Yehud.

MAP 1. The Kingdom of Judah and the Kingdom of Israel. Copyright Reuven Soffer.

SECOND TEMPLE LITERATURE: JUDEA AND ISRAEL

During the Second Temple era (more specifically, from the second century B.C.E.), a shift occurred. In literature of this period, the common name used by Jews and gentiles for the district inhabited by the community throughout most of the period was Judea; the name used for the ethnos was the corollary, Jews.7 These designations are corroborated by evidence on coins. The same picture emerges from official documents quoted in 1 Maccabees,8 which refer to “the Jews” or “the nation of the Jews.” However, Second Temple literature does contain a number of cases in which Israel refers to the nation as well as the land.

But what is the underlying distinction between these two names? What meaning did the Second Temple sources ascribe to the name when referring to the nation? I posit that Judah refers to the core district heavily inhabited by Jews, according to its official name from the Persian period onward. However, when expressing the living memory of the biblical Sons of Israel, Israel serves as the name of both the nation and the land.

Thus, for example, the name Israel appears in the book of Ezra. The returning exiles are described as sacrificing twelve he-goats “according to the number of the tribes of Israel” in order to atone for all of Israel (Ezr 6:17), relating to the memory of the biblical tribes. Similarly, in the first half of 1 Maccabees, Israel connotes the land of the united kingdom in the days of David and Solomon as preserved in collective memory. The use of Israel, therefore, reflects the author’s motivation in illustrating Judah Maccabee and his brothers as fighting across all the districts of the former united kingdom with the aim of restoration.

However, the use of the term Jews for the nation is not restricted to writers native to the province. Josephus and Philo both generally refer to the nation as Jews.9 Both writers employ both Judah and Palestina in reference to the land. Some writers used Israel as the name of the land when expressing an aspiration to restore the golden age of David and Solomon; Philo and Josephus, both of whom were committed to their Hellenistic present, would not have adopted this name.

THE SHIFT FROM JUDAH TO ISRAEL: THE END OF THE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD AND THE RABBINIC ERA

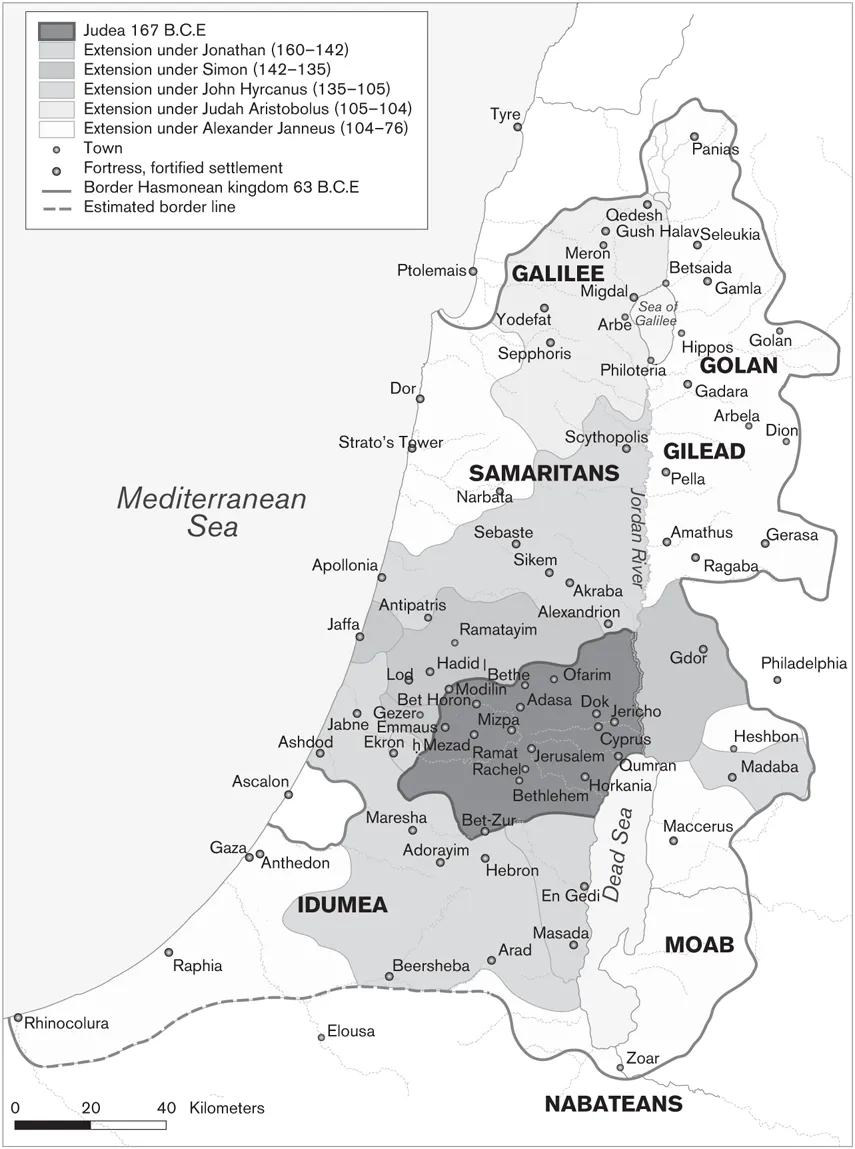

The shift from the name Judah to Israel occurred during the second half of the Hasmonean period and continued during the period of rabbinic literature. This transition is reflected both in literature and on coins,10 specifically through the coins from the Great Revolt of 66–70 C.E. While those from the earlier Hasmonean revolt are marked with the terms Ḥever ha-Yehudim (Council of the Jews), coins from the Great Revolt read Shekel Yisrael, indicating the “measure” of Israel.11

MAP 2. The expansion of the Hasmonean Kingdom. Copyright Reuven Soffer.

FIGURE 1A. Coin of John Hyrcanus with the inscription: “Yehohanan the High Priest and the Council of the Jews.” Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Elie Posner.

FIGURE 1B. Coin of the Great Revolt with the inscription: “Shekel Yisrael.” Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Yair Hovav.

FIGURE 1C. Coin of Bar Kokhba with the inscription: “Shimon Nesi (Patriarch of) Yisrael.” Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

The name Israel also appears in documents from Wadi Murabba’at,12 which likely date to the Great Revolt as well. The letters of Shimon Bar Kokhba, written during his revolt of 132–135 C.E., continue to identify the nation as Israel; coins are stamped with Bar Kokhba’s rank as patriarch of Israel (Nesi Yisrael). In these sources, it is difficult to determine if Israel refers to the political regime or the ethnos or both. However, recently published letters include the term House of Israel (Beit Yisrael) as the name of the regime.13 It bears mention that the official Roman name for the province up until Hadrian was Judea, despite the fact ...