![]()

1

Insights from Research and Practice in Spanish as a Heritage Language

M. Cecilia Colombi

University of California, Davis

Ana Roca

Florida International University

Mi lengua: Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States addresses the issues and challenges of developing and maintaining Spanish as a heritage language in the United States. Our book brings together work that addresses theoretical considerations in the field of Heritage Language Development (HLD), as well as community and classroom-based research studies at the elementary, secondary, and university level. Each chapter includes a practical section titled “Pedagogical Implications for the Teaching of Spanish as a Heritage Language in the U.S.,” which provides practice-related suggestions for the teaching of Spanish as a heritage language to students from elementary grades through the secondary and college levels. The collection of essays in this volume was undertaken in response to the growing and urgent need for scholarly materials in applied linguistics and pedagogy in the specific areas of research on Spanish as a heritage language and the teaching of Spanish to U.S. Hispanic bilingual students in grades K–16.

U.S. Hispanic Population Growth

Unlike the past immigrant waves in this nation’s history, in which sizeable linguistic enclaves of German, Japanese, Polish, and Italian communities gradually diminished, the populations of Spanish-speaking U.S. Latinos and newly arrived Latin American groups have continued to grow, resulting in increased use of the Spanish language. The city of Los Angeles alone has over 4.2 million Hispanics, the largest concentration of Hispanics in the U.S. In a CNN report titled “Will Spanish Become America’s Second Language?” (Hochmuth 2001) the lead reads: “It’s not just your imagination. In cities from coast to coast, the use of Spanish is booming and is proliferating in ways no other language has done before in U.S. history—other than English of course. It’s a development that’s making some people nervous. It’s making others rich.”

According to the 2000 U.S. Census, Hispanics are the fastest-growing segment of the population, totaling 35.3 million, a number that has surpassed the African-American population (34.6 million). If we add into the equation the estimated numbers of undocumented Latin Americans who come into the country every day via Mexico, Canada, and elsewhere (estimated at 4,500,000 undocumented workers by INS, 2002), then we can safely assume that Latinos in the United States likely number more than 40 million and are, without question, the largest minority group in the country. One consequence of this demographic trend is that the use of the Spanish language has increased in the U.S. As the new arrivals interact in Spanish within the community and the schools, we hear more Spanish in public settings and see more Spanish in media and advertising. It is as if the constant influx of new immigrants is providing “booster shots” of the language to Spanish speakers who have been here longer. The demographic changes and the increasing use of Spanish in public, business, and private settings have important implications in modern language education, teacher education programs, policy development, and curriculum and program planning for teachers and students in the twenty-first century.

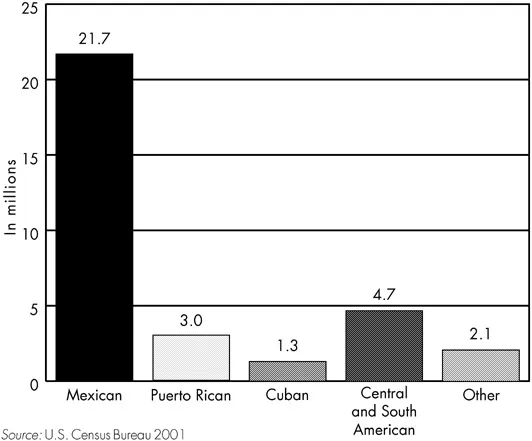

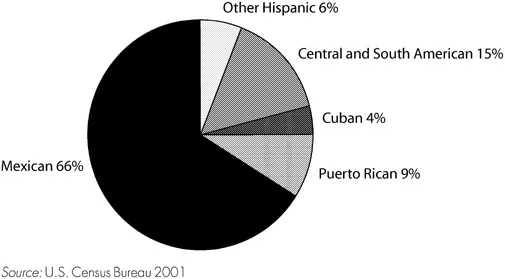

The number of persons who classified themselves as Hispanic in the latest census has grown 60 percent since the previous census. In the 1990 U.S. Census out of a total population of 248,709,803,9 percent of the population, or 22,354,059, were Hispanic. By the 2000 U.S. Census the number of Hispanics grew to 35,300,000 (12.5 percent of the population of 281,421,906). According to the most current census, persons of Mexican origin comprise approximately 66 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population. Among the Hispanic population, Mexicans have the largest proportion of persons under age 18 (38 percent) and in general, the Hispanic population is younger than the non-Hispanic white population.

The projected statistics in 1990 had already indicated that Hispanics (who could be of any racial group) would become the largest minority of the twenty-first century; however that milestone has been reached sooner rather than later than expected. After English, Spanish is the most frequently spoken language in the U.S. In some parts of the country, such as California, Spanish speakers make up more than a third of the total population. Spanish-speaking students make up more than 70 percent of all English learners in our schools, and one in seven school-aged children is from a non-English-speaking background (McKay and Wong 2000). In other words, multicultural classrooms are the norm in our schools today. Together with these demographic changes come new educational challenges.

Figure 1.1 U.S. Hispanic Population, 2000

Students who are heritage speakers of Spanish have typically spoken Spanish as a first or native language or interacted in both Spanish and English at home. The degrees of language proficiency in particular cases and the number of variables in the profiles of these students are complex and dependent on multiple circumstances. Some heritage learners of Spanish may understand basic informal communication but may have limited repertoires and registers and be unable to speak with much confidence in Spanish without resorting to English, their dominant language. Other students may be first-generation immigrants from Latin America who arrived in this country at an early age, having already had some schooling in Spanish. They may be placed in Spanish for Native Speakers (SNS) classes in the United States and find that they are the more advanced students in the class even if they had gaps in their schooling in Spanish in their place of origin. With so many complex variables, proficiency levels, and varied cultural backgrounds, how can heritage language instruction best serve these students who need to recover and/or develop and build upon the language abilities and cultural knowledge that they bring into the classroom? What can successful bilingual education programs teach us about the Spanish heritage language learner? How can the American public and educational policy provide support to help promote heritage language education in the United States that would result in a higher level of bilingualism? What conditions or environments have prevented this thus far?

Figure 1.2 U.S. Hispanic Population in 2000

Language Attitudes and Sociohistorical Factors

As language instructors we need to take into account the attitudinal and sociohistorical factors affecting students in the environment in which we teach. We should understand that teaching Spanish as a heritage language in Los Angeles can and will vary widely from the experience of teaching it in Miami. Even if there are many similarities in the objectives of such instruction, community attitudes toward Spanish and attitudes toward those who use the language may be very different in certain settings and contexts. The majority of Spanish speakers in California are of Mexican background and have a very different history from, say, today’s Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in New York and Cubans and Colombians in Miami. In which cities and in which settings would students feel that being more proficient in both languages would be a personal and future professional or career asset (Boswell 2000)? Do students associate speaking Spanish with being punished in elementary school or do they associate it with praise for maintaining their heritage? Have students had an opportunity to learn about their historical and cultural background or have they been deprived of such instruction by its exclusion or by its stereotyped representation in the curriculum? Finally, what would help Spanish teachers who face classes of U.S. Latino bilingual students of varying backgrounds, cultures, and proficiency levels? What approaches have been used in the past and what could we be doing today to encourage the best practices possible based on research and experience? How can the profession best publicize, in communities and schools, important research results that show the benefits of heritage language education and bilingualism?

INCREASE IN SPANISH HERITAGE LANGUAGE STUDENTS IN SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES: THE GROWTH OF THE FIELD

In public schools and colleges around the nation we have seen a marked growth in the number of students who enroll in courses of Spanish as a second or native language (see Lynch, chapter 2 in this volume). Because of this growth of the Latino population in the schools and colleges, teachers in many cities and regions are voicing an urgent need for professional development in heritage language teaching approaches, new SNS courses, an expanded and articulated curriculum for Spanish speakers, and special tracks and programs that can better address the linguistic, cultural, and pedagogical needs of these students who reflect the wide variety of the peoples in Spanish-speaking Latin America.

These concerns for more materials and professional development workshops were corroborated in a recent national survey conducted by the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (AATSP). The area of teaching Spanish for Native Speakers (SNS), as it is often called, or Spanish as a heritage language (SHL), was rated by AATSP members as a top priority for the association and the profession at large. (To examine the survey, contact the AATSP at www.aatsp.org.) These K–16 teachers are voicing the concerns of many who increasingly find themselves in teaching situations for which they have received little or no training and practically no orientation during their college education or even their graduate training. In the majority of schools of education and foreign language and linguistics departments, most of the course work aimed at educating prospective Spanish language teachers offers little if any preparation in such areas as first language acquisition, theories of reading and writing, bilingualism, and pedagogical issues of heritage language learners (either generically or specifically applied to Spanish heritage speakers in the U.S.). In spite of the fact that the Spanish heritage language population has increased enormously during the last ten years, schools of education—almost without exception—do not require their majors to take courses in the field of heritage language learning and teaching as part of graduation requirements. Indeed, students are lucky to even find elective courses in this area as part of the curriculum.

The area of heritage language learning has been with us for many years now (Lipski 2000). In 1970 the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (AATSP 1972) commissioned a report on teaching Spanish to native speakers in high school and college. It was also during this period that linguists and educators began developing materials for university-level teaching of Spanish to Spanish-speaking college students. Guadalupe Valdés and Rodolfo García-Moya (1976) edited the first collection of scholarly articles on teaching Spanish to Spanish speakers in the U.S. context. This was followed by the first major commercial text for bilingual students: Español escrito: curso para hispanohablantes bilingües (Valdés and Teschner 1977). This pioneering foundational textbook for college level emphasized basic writing (spelling, accentuation, and vocabulary) and aimed at developing advanced literacy in Spanish without undermining the students’ vernacular varieties.

According to the 1990 census, in the 1980s, as more immigrants entered the country, we witnessed an increase of 40 percent in the number of minority language speakers in the United States, as well as an increase in the number of fluent bilingual persons. Contrary to many opinions and as shown by Veltman (1983), immigrants are acquiring English at a rapid pace. It is the respective heritage languages which can erode as generations go by if these languages are not nurtured and supported by families, the communities, and the schools. At the same time, the decade of the 1980s also marked the beginning of the English-only movement’s march on civil liberties. The battle is not over and today’s social and political scenarios show contradictory signs (Crawford 1992, 1999, 2001). California, as an example, where one-third of the population is Latino, has seen the approval of Proposition 227 (against bilingual education, in 1998) and Proposition 187. (The latter, passed in 1994, denied access to education and health services to undocumented workers; it was declared unconstitutional by the federal government and was never implemented.) English as an official language was approved in the mid-1980s in California, as well as in many other states with significant Latino populations, such as Arizona and Florida.

In 1981 Guadalupe Valdés, Anthony Lozano, and Rodolfo García-Moya coedited Teaching Spanish to the Hispanic Bilingual, addressing issues related to Spanish language teaching in bilingual communities. As the title reflects, this book focuses on the maintenance and development of Spanish and includes theoretical studies in dialectology, pedagogical recommendations for SNS courses, sample course syllabi, and evaluation procedures. Although Spanish had been taught to Spanish bilingual students before, the sociolinguistic constraints of the Latino communities in the U.S. had not been totally acknowledged or dealt with in any significant and practical manner until the publication of this book. This is in spite of the AATSP’s position on the subject, published in the 1970s in an issue of Hispania and reproduced by the Government Printing Office (AATSP 1972). In 1982 Joshua A. Fishman and Gary D. Keller published the anthology Bilingual Education for Hispanic Students in the United States, with a special emphasis on language attitudes, language variation, educational approaches, and child language acquisition.

In the 1990s many more programs and courses for native or bilingual speakers began to be implemented in colleges and universities across the country, although in many cases (as happens with bilingual education programs) these programs did not receive sufficient funding or have assigned teachers and instructors who were properly prepared for teaching Spanish to bilingual students. In 1993 Barbara Merino, Henry Trueba, and Fabián Samaniego edited a book titled Language and Culture in Learning: Teaching Spanish to Native Speakers of Spanish that addressed the challenges of developing Spanish as a minority language in the educational context. This book presents sociolinguistic and language acquisition studies, as well as sample practical curricular and program practices.

More recently, M. Cecilia Colombi and Francisco Alarcón (1997) coedited a collection of essays devoted to the teaching of Spanish to native speakers, called La enseñanza del español a hispanohablantes: Praxis y teoría. This volume focuses on linguistic, cultural, and institutional aspects of the teaching of Spanish to native speakers and provides theoretical and practical implications for the classroom.

In 2000 the AATSP asked its National Committee on Spanish for Native Speakers to write and edit the first practical handbook for teachers K–16 on Spanish for Native Speakers (AATSP 2000). Since this handbook appeared, there has been no other book especially oriented toward the teaching of Spanish as a heritage language in the U.S. Therefore, our book fills this void with representative recent studies in the field from which practical implications for instruction can be drawn.

We have divided this collection into two parts: part I, Spanish as a Heritage Language: Theoretical Considerations and part II, Community and Classroom-based Research Studies: Implications for Instruction K–16. Part I covers the current state of Spanish heritage language development in the United States. Part II is a selection of community and classroom-based studies of various levels of education (elementary, secondary, and college) from different regions of the country as far-reaching and varied as Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, California, Wisconsin, and Maryland. These essays examine such aspects as young people’s attitudes toward English and Spanish, writing strategies, reading acquisition, oral production and development, and issues of revitalization or eradication of a Chicano variety of the language.

Part I. Spanish as a Heritage Language: Theoretical Considerations

In “Toward a Theory of Heritage Language Acquisition: Spanish in the United States,” Andrew Lynch offers an overview of the different theoretical models that have been applied to the study of Spanish as a native language in the U.S., most of which have been adapted from the field of sociolinguistics and Spanish language acquisition (SLA). He addresses the necessary relationship between heritage language acquisition (HLA) and SLA in view of the future of Spanish language instruction in the United States. He suggests nine principles to develop a model of HLA that researchers and practitioners should take into account when they focus on Spanish as a heritage language. These principles are: (1) the purposeful acquisition principle, (2) the incidental acquisition principle, (3) the simplification principle, (4) the variability principle, (5) the discourse principle, (6) the utility principle, (7) the social relevance principle, (8) the social identity principle, and (9) the language recontact principle. Lynch presents a clear and thorough perspective of the directions that HLA studies should pursue to ensure a societal bilingualism that will legitimize Spanish and its speakers in the United States as well as expand its domains in the global future of our nation.

María Carreira, in “Profiles of SNS Students in the Twenty-first Century: Pedagogical Implications of the Changing Demographics and Social Status of U.S. Hispanics,” describes the different language competency profiles of the heritage speakers according to the implications of different research studies and the census data. Carreira points out that while states like California, Arizona, and Colorado have severely restricted bilingual education in spit...