![]()

PART I

Causes of Interest Group Competition

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Competition and Interest Group Politics

ARGUING that Americans are competitive is hardly a great, new insight. Perhaps because we want to believe that free market competition leads to financial success or just because we live in a society with limited resources and opportunities, we seem to be constantly competing. We compete in sports to see who is physically superior so we can cover the winner in glory and medals while we send all other participants home tired and despondent. We compete in relationships, striving with others for recognition from parents, friends, bosses, and potential mates. When we cannot resolve our differences informally, we compete in court, forcing losing parties to transfer valued assets, usually money, to winners while gaining nothing in return. Competition means risking effort, resources, and even self-esteem in a struggle to achieve goals desired by others but not easily shared, even if we are willing to share. If there is a winner, then there must be at least one loser who may have lost more than what the goal was even worth by choosing to compete.

It comes then as no surprise that our politics, which determine who has the right to make public law and divvy up public resources, is competitive. The party that wins a majority of seats in Congress gets to govern; the losing party gets the back benches. A presidential candidate wins the general election and gets to set agendas; the other would-be leaders suffer ignominious defeat. Pro-life advocates will either ultimately succeed in overturning Roe v. Wade or pro-choice proponents will maintain the status quo. Journalists emphasize winners and losers when they write about politics, whether in tax reform legislation (Birnbaum and Murray 1986), business deregulation (Birnbaum 1992), or campaign finance reform (Drew 1999). Even many scholars portray politics as competitive, as exemplified in Harold Lasswell’s (1936) famous book Politics: Who Gets What, When, How.

The Constitution’s authors appear to have believed American politics would be competitive. Why else would checks and balances limiting political power have such a prominent role in their constitutional philosophy? Societies, James Madison argued, naturally subdivide into factions of citizens bound by common needs, beliefs, or desires, which he called “factions” and “interests.” Consequently, he argued, the shared interest of one faction was likely to infringe on those of others, making it impossible for government to satisfy all factions simultaneously; thus he concluded in Federalist No. 10 that group competition was both threatening and inevitable. So, were he alive today, Madison might be surprised to learn that for decades, scholars have largely rejected the idea that social groups regularly compete for power and influence in American politics. Social factions may have competing interests in the abstract, prevailing theory holds (after overthrowing an older tradition that assumed Madison was right), but legislators and lobbyists found it to their advantage to quietly partition power and political territory among themselves rather than openly compete. Understanding how this theory came to be and why it is now time bound is essential to make the case that group competition is alive and well today and deserves to be studied. It is, I believe, essential for identifying a new theoretical step to take, one that synthesizes two literatures that have come to dominate the study of advocacy and will allow us to better understand the modern, often competitive, world of interest group politics.

From Competitive Pluralism to Interest Group Balkanization

The intellectual history of interest group scholarship is well documented and does not need to be repeated here beyond what is pertinent to my argument (see Baumgartner and Leech 1998; McFarland 2004 for good histories). Nonetheless, I begin where most histories of group politics start, with Arthur Bentley.

Pluralism and Its Critics

An early precursor of the Behavioral Revolution and the scientific study of politics, Bentley (1908), the intellectual partner of John Dewey, argued that politics was fundamentally about competition between groups of individuals bound by common experiences, desires, and beliefs.1 Indeed, Bentley argued that groups are the basic units of society, so much so that the behavior of individuals cannot be understood outside of their group contexts; their wants and desires are defined by the group’s collective identity, or its “interest.” Large nations like the United States contain so many groups, drawn from different ethnic backgrounds and walks of life, that it is nearly impossible for clear and enduring majorities to emerge and provide consensus on the rules of society and the use of public resources. Sounding like Madison, Bentley argued that what we have instead are pluralities of group interests, often with beliefs and desires so different from each other that demands articulated by one group are likely to be perceived as threatening to the interests of others. Using political advocacy to embody these interests in public policy transforms this social competition into political competition.

Bentley’s work was largely ignored in his own time, but forty years later elements of his belief in politics as competition among a plurality of groups were resurrected as the basis of an ambitious theory of politics and government. For pluralist scholars such as Earl Latham (1952) and especially David Truman (1951), competing social interests were the explicit cause of the mobilization of political interest groups. When members of one faction perceive those of another to be advocating for policy outcomes that threaten their interests, they organize and employ lobbyists to push back against these encroachments. This lobbying, in turn, prods other social groups to organize, continuing a wave of mobilizations that Truman labeled “Disturbance Theory.” Compromise between these competing interests leading to new law and a division of public resources simply reflected a balance of power with policy favoring the stronger. For pluralists this mobilization and competition was the engine driving American politics. Indeed, it was more than just a theory about how American politics operated; it became a normative blueprint for how the government and political system ought to function (Dahl 1956). Thus, a nearly full-blown paradigm shift occurred in political theory when critics of pluralism managed to knock out its foundations and reverse its conclusions. Suddenly, prevailing theory held that no meaningful interest group competition took place in American politics at all.

Not that all critics of pluralism, even of Robert Dahl’s (1961) less grandiose version of it, directly challenged its assumption that American society is a plurality of social groups with competing interests. Theodore Lowi (1969), E. E. Schattschneider (1960), and even C. Wright Mills (1956) were more or less willing to accept Bentley’s and even Madison’s view of society as composed of competing interests; they simply doubted that competition was manifesting as actual political conflict. Competition might exist in the abstract, but due to a combination of political pressure and human obfuscation it was not stimulating widespread mobilization and conflict because not all groups perceived their interests to be threatened. The reason, Schattschneider (1960) argued, was that elites who benefit from serving the interests of one group at the expense of another could, and very often did, frame issues and the policies addressing them as unthreatening or even benevolent. A policy status quo favoring privileged groups could be perpetuated and members of affected groups kept quiescent because the latter were left unaware that their interests were being harmed when lawmakers served the former’s demands (Bachrach and Baratz 1962). Even if they did realize the threat, Mancur Olson (1965) demonstrated that we still cannot assume that members of the affected factions will mobilize to actually compete in the political arena. Rational self-interest may prevent individuals from contributing to a potentially mobilized group’s actual organization.

These arguments became part of a larger literature on interest group balkanization and policy stasis that emerged in the late 1960s and to a considerable extent holds sway today. The core assumption is that political institutions, Congress in particular, have been intentionally designed in a decentralized fashion with multiple power centers because such a structure more readily allows elites to quietly aim benefits at constituencies key to their political survival without appearing to threaten the interests of others (Lowi 1972). After revolting against House Speaker Joseph Cannon in 1910, committees in Congress gained considerable autonomy from party leaders and the power to dictate policy outcomes within well-defined domains (or jurisdictions) of lawmaking, such as agriculture, defense, and transportation (Deering and Smith 1997, 30). Norms of self-selection and property rights made it possible for legislators to win and retain seats on committees with jurisdiction over policies crucial to interests in their home districts and states, interests so politically mobilized that appeasing them was crucial to their own reelection.

Most of these mobilized interests were, broadly speaking, economic in that they sought financial support and regulatory protection for their members. Commodities growers desired price supports to ensure profits, highway and defense contractors lobbied for project funds, and manufacturers wanted regulation to stymie domestic and foreign competitors (Stigler 1971, 1972; Peltzman 1976). Groups with similar demands only had to lobby a single committee with jurisdiction over their issues. Fortunately for them, committee legislators could afford to provide everyone benefits because budgets and discretionary spending were growing from the 1950s through the 1970s; deficit spending made more money available even when these surpluses proved inadequate (Peterson 1992).

John Mark Hansen (1991), for example, describes how pro-farm state legislators made careers for themselves by serving agriculture constituencies and their interest groups in the House and Senate Agriculture and Appropriations committees. Lobbyists for farm special interests were given access to the policymaking process by these legislators because they had a mutual interest in keeping benefits flowing to group members. Legislators needed to know how best to serve these crucial electoral constituencies, and lobbyists were in positions to provide such information and to help members of Congress work the system to make it happen. Lobbyists would then trumpet their committee ally’s accomplishments in the home district or state and raise money for their “friend’s” reelection. Building and maintaining mutually beneficial relationships was how lobbyists normally did business, so it is little wonder that in his study of interest groups during the committee government era, Lester Milbrath (1963) saw lobbyists as little more than benevolent aides to legislators, not as corrupting parasites. To retain and expand their influence, lobbyists simply needed to help their friends stay in office. All their friends had to do was keep down or co-opt potentially competing interests.

Boldly claiming that serving mobilized interests benefited everyone (it was “patriotic” or “pro-jobs”) kept other, latent interests from seeing any harm done to them. New interests that did manage to mobilize did not demand that benefits be taken away from those already established; they just wanted their own piece of the action. Legislators thus “bought off” these new claimants by giving them a slice of the public pie, which of course gave these interests an incentive to also support the status quo (Davidson 1981).2 Political fallout from the greater deficits all of this buying-off produced were small because the costs of funding these policies fell on the public in the form of taxes and debt, diffuse enough sources of revenue to prevent most people from realizing that there was any cost for helping these well-heeled special interests (McCool 1990). Even if some did realize it, the highly decentralized nature of Congress made assigning blame or enacting reform difficult (Dodd 1977). The norm of reciprocity ensured that each committee’s bill parceling out benefits went unamended on the floor, logrolling and back-scratching being the order of the day, and autonomy made it easy for committees to bottle up bills threatening the status quo (Shepsle 1979).

An Analytical View of Interest Groups and Subgovernments

At this point it might be useful to develop a more analytical view of lawmaking in a world of interest groups balkanized in policy domains partly because it helps set up the competitive model in the next chapter. Formal theories tend to see legislation as the manifestation of choices to address issue questions on the government’s decision agenda at particular points on continua of theoretically infinite possible policy outcomes (e.g., Downs 1957; Hinich and Munger 1997). An outcome dimension represents some degree of government spending or level of regulation on the behavior of individuals or organizations, with an actual policy serving or harming an interest group located at one (and only one) position. Points on the left-hand, or liberal, side represent greater levels of spending or protectionist regulation than those on the right-hand side. Lacking counteractive lobbying from competing groups or other countervailing forces, legislators are only limited in how much they can provide, or how far left or right on the continuum a policy is, by the size of the public pie and perhaps some sense of fiscal and social responsibility.

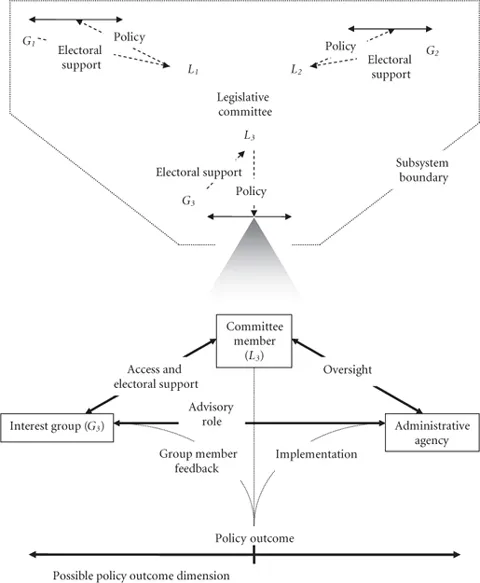

Figure 1.1 shows what a policy subsystem might look like. Around a committee of three legislators shown in the upper part of the figure are three “client” interest groups, each connected to their patron legislator who provides them with policy benefits. The policy provided to each group is marked on a dimension unique to that group because only that group’s members care about the issue: Only cane growers in Florida care about their level of sugar subsidy, only dairy farmers care about the fixed price of milk, only midwestern corn growers care about ethanol subsidies—though all are contained in the agriculture policy domain. As long as these groups dutifully repay their patron legislator’s largess with electoral votes and campaign contributions, the status quo level of benefits will remain and perhaps even increase incrementally over time. As the lower portion of the figure demonstrates for group G3 and legislator L3, legislators establish administrative agencies within the executive branch in order to deliver the benefits to the client group. Agency heads are rewarded with large budgets and little oversight when they ensure that client group members receive their benefits, which provides them with an incentive to support the status quo as well. Such mutually beneficial relationships for all three groups in figure 1.1 is what Douglass Cater (1964) termed a “subgovernment,” though “iron triangle” has become the more popularized term.

A unique policy dimension for each group means that the interests of groups enfranchised by committee legislators do not overlap.3 The issue dimension for one group in figure 1.1 is isolated from the others, or as formal theorists put it, preferences are “separable.” Legislators and lobbyists for these groups have defined the issues to justify the status quo (“protecting the American family farmer” or “what is good for business is good for America”) and to suppress the perception that benefits to one group are coming at the expense of others, so every group in the subgovernment gets policy that satisfies member interests without hurting each other. The subsystem is static because the policies rarely ever change. Unmobilized factions are left oblivious to the harm done to them and therefore remain latent rather than strive to influence where legislators choose to enact policy on a contested policy dimension. Interest group conflict does not exist because there does not appear to be any threat to defend against.

Figure 1.1. Congressional committee members and client groups in a subgovernment

Growth, Change, and Competition in Interest Group Politics

Although accepted by many scholars even today, perhaps because it appeals to their skeptical nature more than the pluralist’s balance-of-power view, actually little systematic evidence exists to support the theory that such exclusive subgovernments are current political realities. Indeed, some doubt has been expressed as to whether they ever existed (Clemens 1997; Tichenor and Harris 2002). Much of what has been written by Bernstein (1955), Cater (1964), McConnell (1966), and Lowi (1969) relies on case studies of policymaking in one or a few domains in the 1950s and 1960s and, I argue, is time bound because...