![]()

Part I

Background

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Today’s Challenging Legislative Environment and the Politics of Efficiency

For some time, I’ve had a growing conviction that Congress is not operating as it should. There is too much partisanship and not enough progress—too much narrow ideology and not enough practical problem solving. Even at a time of enormous national challenge, the people’s business is not getting done.

—SENATOR EVAN BAYH (D-IN), on why he was retiring from the Senate, Los Angeles Times, February 16, 2010

On September 9, 2009, President Barack Obama addressed a joint session of Congress on the need for major health care reform. Standing before his fellow elected officials and recent congressional colleagues, Obama declared that the “time for bickering is over” and presented his case for a $900 billion plan that would build on the existing employer-based health care system. In the middle of his speech, after he chided opponents for distorting his plan and insisted that it would not cover illegal immigrants or fund abortions, Republican representative Joe Wilson of South Carolina shouted “You lie” (Connolly and Shear 2009).

Congressional leaders quickly condemned Wilson’s behavior. He apologized, and President Obama accepted the apology. Rank-and-file Democrats, however, were not so easily appeased. They called for a formal reprimand, and on September 16, 2009, the House of Representatives passed a “resolution of disapproval” against Wilson on a largely party-line vote (Kane 2009). While the Democrats formally rebuked Wilson, the base of the Republican Party embraced him. He reportedly became a minor celebrity among conservatives and “fund-raising star,” receiving thousands in campaign contributions, garnering invitations from Republican candidates across the nation, and posing for photographs with the party faithful for $150 (Associated Press 2009).

It is tempting to dismiss this entire episode as overblown and shortlived, a nice moment of drama for the media that quickly passed as new events grabbed the headlines. But Representative Wilson’s outburst and its divisive aftermath were not an isolated event. They are emblematic of the sharply partisan landscape in Washington, which reflects several recurring attributes of contemporary politics—namely, the emergence of narrow political majorities and ideologically polarized parties in Congress.

The evidence of shrinking majorities in Congress is striking, especially when placed in historical context. During the nineteenth century, the average margin of congressional control—the difference between the majority and minority parties relative to the total number of seats—was 27.4 percent (Young 2006). In the post–World War II era, the average margin of congressional control fell nearly in half, to 14.3 percent, but healthy majorities were still common. From 1955 to 1993 Democrats held more than 60 percent of House seats in eight of twenty congressional sessions and more than sixty seats in the Senate seven times, and they nearly reached these thresholds in another six sessions, four in the House and two in the Senate.1

Things changed with Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” in 1994. From 1994 to 2009 the margin of party control plummeted to 5.4 percent in the House and 5.2 percent in the Senate (Young 2006). During this period Democrats had more than 60 percent of House seats and sixty Senate seats only once in eight sessions. Moreover, this supermajority in the Senate, which emerged after the election of President Obama in 2008, was tenuous. It included sixty votes only if one counts the two Democratic-leaning independents and only because a Republican senator, Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, switched parties while making it clear that he would not be an automatic Democratic vote. It was also fleeting. Before the 2010 midterm elections swept the Democratic Party’s majority out of the House and significantly reduced the party’s majority in the Senate, Republican senator Scott Brown of Massachusetts wrested the critical sixtieth seat from the Democrats in a special election after Senator Edward Kennedy’s death (largely by running against the incumbent Democratic majority and President Obama’s efforts to pass comprehensive health care legislation).

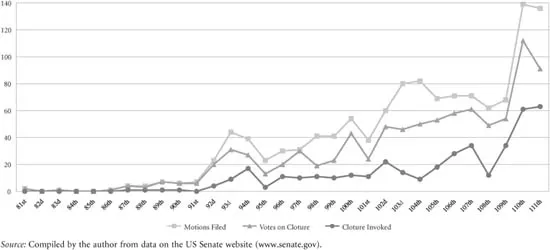

Under these conditions, the majority party typically cannot unilaterally advance its policy agenda at the federal level, even when it nominally controls Congress and the presidency. Supermajority requirements in the Senate, such as the need for sixty votes to overcome a filibuster, require party leaders to reach across the aisle and muster at least some support from the opposing party.2 This is especially true today, because the use of the filibuster has reached unprecedented levels. According to the Senate’s own data, the filing of motions for cloture—the procedural mechanism for ending filibusters—has grown dramatically during the past fifty years. From 1949 to 1960 a total of 4 cloture motions were filed; but from 1999 to 2010 a total of 547 cloture motions were filed, 136 in the 111th Congress alone (fig. 1.1). These numbers understate the practical importance of supermajority requirements in the contemporary lawmaking process because they do not include other procedural mechanisms that impose sixty-vote thresholds, such as budgetary points of order,3 or account for how the threat of these obstacles looms over legislative efforts.4

Reaching out to members of the minority party, however, creates a political quandary. Efforts to appeal to members of the opposition threaten to alienate the majority party’s rank and file, whose loyalty is equally essential to building winning legislative coalitions. This balancing act has become increasingly precarious as ideological tension within Congress has grown over time (see, e.g., Rohde 1991; Aldrich 1995; Groseclose, Levitt, and Snyder 1999; Sinclair 2000a; Roberts and Smith 2003; Jacobson 2007; Poole and Rosenthal 2007). According to Poole and Rosenthal (2007), who have developed widely accepted ideological scores for each member based on an analysis of roll call votes, the distance between the median voter in the Republican and Democratic parties has doubled since the 1980s. Equally important, the distribution among members has shifted. Whereas members were once somewhat evenly distributed across the ideological spectrum, they now tend to cluster at the poles, with Republicans grouped on the right and Democrats clumped on the left.5

The point is not that passing major legislation is impossible in an age of polarized and closely divided political parties (Mayhew 2005; Sinclair 2000b). There have been many examples of legislative success on highly contentious issues since 1994, such as the enactment of extensive welfare reform under the Bill Clinton administration, the creation of an expansive prescription drug benefit under the George W. Bush administration, and the passage of the massive fiscal stimulus package, national health care legislation, and sweeping financial reforms under the Obama administration. The point is that the combination of narrow majorities, polarized parties, and supermajority requirements in the Senate creates distinct political challenges (Binder 1998), which often necessitate “unorthodox law-making” (Sinclair 2000b). Thus, for example, senators can try to enact a bill using the budget reconciliation process that limits floor debate in both chambers and precludes filibusters.6 Or they can try to build coalitions that avoid straight party-line votes and are broad enough to overcome supermajority requirements in the Senate and/or divided government.

Figure 1.1. Senate Action on Cloture Motions for Ending Filibusters, 81st to 111th Congresses, 1949–2010

One such coalition-building strategy involves the “politics of efficiency,” which frames reforms in terms of their potential to improve the overall efficiency of existing policies and institutional arrangements. The politics of efficiency can potentially diffuse partisan tensions because there are no obvious ideological divisions over making policies and institutions run more smoothly; therefore, the goal of enhancing efficiency seems a valence issue with broad cross-party appeal (see, generally, Esterling 2004; Burke 2002). Consistent with this logic, reformers have called on the politics of efficiency (in some form) since at least the Progressive Era, when advocates promoted their agenda over the opposition of entrenched political parties on the grounds that creating better and more efficient government programs and services was neither inherently Republican nor Democratic. It was merely “good government.” The politics of efficiency was also used throughout the 1980s and 1990s to build support for free trade policy, deregulation, and tort reform, as reformers contended that creating the conditions for greater competition and freer markets—such as lower trade barriers, fewer rules, and less litigation—would engender greater efficiency for the benefit of both consumers and producers (Derthick and Quirk 1985).

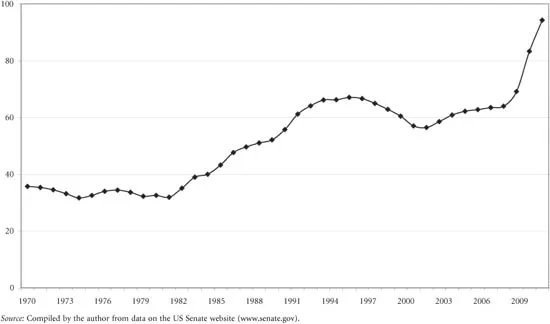

The politics of efficiency may be particularly salient in coming years given the looming fiscal crisis in the United States. The government reports that the annual federal deficit has more than doubled since 2000 and will reach $1.3 trillion in fiscal year 2011, or about 10 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product, while the cumulative debt is projected to hit nearly 95 percent of the gross domestic product, up from 36 percent in 1970 (fig. 1. 2). The public has begun to take notice, for it has ranked deficit reduction as a top priority, placing it above health care and education (Rasmussen Reports 2009, 2010). The appeal of the politics of efficiency under these conditions is simple. Whereas reducing deficits by raising taxes or retrenching programs is highly partisan and contentious (see, generally, Pierson 1994), squeezing waste out of existing policies and institutions promises to reduce costs without cutting benefits. As such, the politics of efficiency offers something for nothing, which should entice policy entrepreneurs in both political parties.

Of course, theory is one thing; practice is quite another. This book explores the politics of efficiency in the case of the asbestos litigation reform following the 2004 presidential election during the 109th Congress. For reasons discussed below and elaborated in later chapters, this case offers a useful window through which to view the politics of efficiency in action. The main reason is that efficiency arguments were central to promoting asbestos litigation reform in the 109th Congress. Indeed, the politics of efficiency has been at the center of asbestos injury compensation issues since the early 1980s, when advocates for reform both in and outside Washington framed the need for legislative action in terms of the effectiveness and efficiency of litigation as a means of addressing the asbestos crisis. In addition, the politics of efficiency seemed promising for building a winning bipartisan reform coalition in the 109th Congress for a host of political and policy reasons, including the fact that reform promised to deliver billions of dollars in savings to claimant and business interests. Yet no such coalition emerged, and the reform legislation failed.

Figure 1.2. Gross Federal Debt as a Percentage of GDP, 1970–2010

The question is, Why? Why did the politics of efficiency fail to produce an effective legislative coalition for reforming a system that nearly every-one—the president, congressional leaders, the Supreme Court, and prominent policy analysts—agrees is wasteful, inconsistent, and, in some cases, fraudulent? What does this failure teach us about the promise and limits of the politics of efficiency as a coalition-building strategy and, more generally, the prospects for significant institutional change in today’s challenging legislative environment?

THE PUZZLE: A CLOSER LOOK

Exploring the recent politics of asbestos injury compensation takes the analysis into largely uncharted territory. A superb literature documents the cost and inconsistency of asbestos litigation and describes the pertinent judicial decisions and litigation strategies used by lawyers and judges during the past thirty years (e.g., Kakalik et al. 1983; Hensler et al. 1985; Sugarman 1989; McGovern 1989; Hensler et al. 2001; Hensler 2002; Issacharoff 2002; Carroll et al. 2002, 2005; White 2002, 2005; Carrington 2007; Hanlon and Smetak 2007; and see, generally, Nagareda 2007). A smaller body of prescriptive work debates what Congress should do in response to the asbestos crisis (e.g., Glass 1983; Cardozo Symposium 1992; Schwartz, Behrens, and Tedesco 2003; McGovern 2003).

Almost no scholarly attention, however, has been paid to the politics of asbestos injury compensation. Instead, there are several journalistic accounts. Some of these accounts are now dated (Brodeur 1986), and others focus mainly on Libby, Montana—the home of a vermiculite mine that caused this once-pristine town to be designated a toxic waste site (Bowker 2003; Peacock 2003; Schneider and McCumber 2004). To the extent that these accounts touch on the broader politics of asbestos injury compensation, they are impressionistic, providing interesting nuggets of information but no sustained analysis.

Looking beyond the specific literature on the asbestos problem, there is a general literature on the politics of civil litigation in the United States (e.g., O’Connell 1979; Epstein 1988; Elliott and Talarico 1991; Campbell, Kessler, and Shepherd 1995; Kagan 1994, 2001; Barnes 1997; Burke 2002). But the failure of the politics of efficiency in the case of asbestos litigation reform is more, not less, puzzling in light of this body of work. As is more fully described in chapter 3, this literature provides a laundry list of factors that should increase the chances of successfully using the politics of efficiency to build a coalition that can overcome the expected opposition from trial lawyers and pass some type of reform: (1) support from strategically placed policy entrepreneurs, (2) Republican majorities, (3) bipartisan support, (4) judicial calls for legislation, (5) high administrative costs and legal uncertainty, and (6) an expert consensus on the lack of secondary policy benefits of litigation. All these factors were present during the 109th Congress, but the politics of efficiency still failed to create a sufficiently broad bipartisan coalition to push reform across the finish line.

The questions remain: Why did the politics of efficiency fail, given these seemingly favorable political and policy circumstances? Why did stakeholders other than lawyers fail to unite behind reforms that aimed at replacing a notoriously inefficient, inconsistent, and sometimes fraudulent system of compensation that was costing them billions of dollars? What are the broader lessons of this failure?

OVERVIEW OF THE ARGUMENT

This book examines these questions by drawing on multiple sources, including the legislative record, judicial decisions, media accounts, and participant interviews, and by employing multiple methods, including qualitative and quantitative analyses. It aims to describe the recent politics of a major, ongoing public health crisis and to use this substantively important case as a lens to examine the promise and limits of the politics of efficiency. In exploring this issue the book takes up a host of others, including the scope and nature of civil litigation reform, the US system’s current capacity for institutional change, and how scholars should grapple with the complexity of contemporary American policymaking.

It needs to be stressed at the outset that this is not a work of pure policy or legal history. No effort is made to provide a comprehensive chronology of recent events in the area of asbestos injury compensation or a detailed examination of the many important legal developments within asbestos litigation. Instead, this book offers a critical case study that aims to identify patterns of interbranch governmental relations that help reveal institutional constraints on improving public policy and the operation of the US legal system for the benefit of both ordinary Americans and businesses. (Appendix A further explains the relevant case study methods, including both their strengths and weaknesses.)

The analysis proceeds in five chapters, which have been divided analytically into three parts: background, case study, and implications. The present chapter has given some of this background, and chapter 2 provides the rest. It offers an overview of the asbestos crisis in the United States by tracing the rise of asbestos consumption and litigation, the growing critiques of asbestos litigation and the related rise of the politics of efficiency, and the institutional response leading up to the latest congressional efforts to reform the system. It argues that the asbestos crisis is best understood as a multifaceted problem that encompasses both a global health crisis and a national institutional crisis, which reflects a deeply layered approach to compensating asbestos victims.

With a better understanding of the underlying policy problem in place, the analysis turns to part II, the case study. Chapter 3 introduces the case by explaining why recent efforts to enact major asbestos injury compensation reform provide a theoretically interesting vantage for exploring the politics of efficiency as a legislative strategy. Chapter 4 provides the heart of the empirical analysis. Drawing on participant interviews and the legislative record as well as analyses of roll call votes and media content, it examines the rise and fall of asbestos litigation r...