This is a test

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

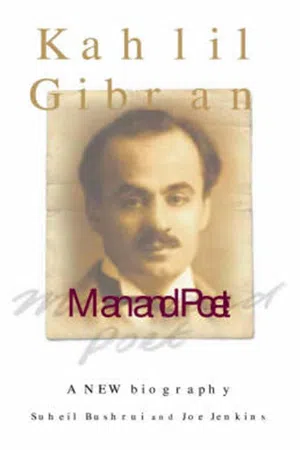

The definitive biography of one of the world's most popular writers Bushrui and Jenkins have produces a biography that meticulously explores the complex intricacies of this philosopher-poet. Offering fresh insights into his life, times and work, this unique book sets new criteria in evaluating Gibran.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Kahlil Gibran by Suheil Bushrui, Joe Jenkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Beginnings

(1883–1895)

I

Gibran Khalil Gibran, who became known as Kahlil Gibran,1 was born in the far north of Lebanon on 6 January 1883.2 The village of his birth, Bisharri, is perched on a small plateau at the edge of one of the cliffs of Wadi Qadisha, known as the sacred valley. Towering above is Mount Lebanon.

Khalil Gibran, the poet’s father, whose name the child inherited as his middle name according to Arabic custom, was a tax collector in Bisharri. A strong, sturdy man with fair skin and blue eyes, he had received only a basic education, yet was a man of considerable charm who liked to cut a dash. Although he owned a walnut grove Khalil Gibran’s meager income soon evaporated as he fed his extravagant habits – alcohol and gambling. Regarded by some as “one of the strong men of Bisharri,” he was by all accounts a hard man to live with, and his wife and children feared him.3

The son in later life expressed filial feelings toward his father – an attempt to disguise the harsh reality of what was undoubtedly a difficult relationship:

I admired him for his power – his honesty and integrity. It was his daring to be himself, his outspokenness and refusal to yield, that got him into trouble eventually. If hundreds were about him, he could command them with a word. He could overpower any number by any expression of himself.4

However, in truth Kahlil’s relationship with his father was difficult and often strained. The boy never felt very close to this autocratic, temperamental man who was hostile to his artistic nature5 and was not a loving person.6

His mother, on the other hand, evoked in the child feelings of deepest affection and admiration. Kamileh Rahmeh was the daughter of a Maronite clergyman named Istiphan Rahmeh. She is described as a thin, graceful woman with a slight pallor in her cheeks and a shade of melancholy in her eyes.7 Kamileh had a beautiful singing voice and was a devoutly religious person. When she reached marriageable age she was married to one of her own clan, her cousin Hanna ‘Abd al-Salaam Rahmeh. However, like many Lebanese of his time, he emigrated to Brazil to seek his fortune, but while he was there he died, leaving Kamileh with a son Boutros (or Peter). Some time after Hanna Rahmeh’s death, the young widow married Khalil Gibran. After the birth of her son Kahlil, two daughters were born to the couple, Marianna8 in 1885 and Sultanah9 in 1887.

In contrast to her husband, Kamileh was an indulgent and loving parent, and ambitious for her children. Although without formal education, which at the time was considered useless, if not dangerous, for women,10 she possessed an intelligence and wisdom that had an enormous influence on her younger son, who later said of her: “It is her mothering me I remember – the inner me.”11 Fluent in Arabic and French, artistic and musical, Kamileh ignited Kahil’s imagination with the folk tales and legends of Lebanon, and stories from the Bible.

In one of his earliest Arabic works, al-Ajnihah al-Mutakassirah (The Broken Wings), the son’s deepest respect for motherhood is revealed:

The most beautiful word on the lips of mankind is the word “Mother,” and the most beautiful call is the call of “My mother.” It is a word full of hope and love, a sweet and kind word coming from the depths of the heart. The mother is every thing – she is our consolation in sorrow, our hope in misery, and our strength in weakness. She is the source of love, mercy, sympathy, and forgiveness.12

Coming from a family steeped in the Maronite tradition, Kamileh had contemplated joining the nunnery at Saint Simon in northern Lebanon before her first marriage.13 Maronite Christianity, an ancient sect, emerged in the fifth century when the early Christians of Syria pledged their allegiance to a hermit, Marun, whose gifts and virtues brought him many disciples. Using a ritual alive with the Aramaic tongue of Jesus and a liturgy that is among the oldest and most moving in the Christian Church, the Maronites were able to protect their traditions due to the physical remoteness of the mountain region. The spiritual nature of Gibran’s mother and the impressions that the child received from the mystical ceremonies of the Maronites remained with him all his life.

Under the huge shadow of Mount Lebanon, Kamileh, the priest’s daughter,14 and her handsome husband reared their family. Although life was hard it was not unendurable, and the rugged and resourceful villagers eked out a living on the thin crust of the soil.

II

However, the people of Lebanon faced a threat more terrifying than poverty. Only a generation before, the country had been propelled into a terrible civil war. Sectarian violence which broke out in 1845 reached shocking proportions in 1860, in one of the most terrible religious massacres in history.15 Thousands of Christians were slaughtered, many at the altars of their churches. Pillage, plunder, and the burning of villages and towns were common occurrences, resulting in streams of refugees. In all more than 30,000 Christians, mainly Maronites and Greek Orthodox, were massacred in this dark age by the Druze, with the encouragement of the Ottomans.16

In a region that perhaps more than any other had been a meeting-point of East and West, as well as a rich melting-pot of religions, the utter turmoil generated by this explosion of sectarian violence and political upheaval etched a deep scar on the consciousness of Khalil and Kamileh’s generation. Up to the 1840s Shi‘ite and Sunni Muslims, Greek and Syrian Catholics and Orthodox, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Maronites, Nestorians, Jesuits, Jacobites, Jews, and Druze, had all lived together in relatively peaceful coexistence.

Of all the provinces living under the oppressive rule of the Ottoman empire – which stretched from Hungary to the Arabian Peninsula and up to North Africa – Lebanon seemed to be the most modern. Over the centuries it had opened up to Western influences, and the people of Lebanon possessed a high level of literacy because of a variety of schools founded by European missions. Since the Turks had extended their empire to include Lebanon in 1516, under the illustrious Sulayman I, Lebanese history had been dominated by two rulers, whose attempts over the years to impose political unity and secure national autonomy failed with the tragic events of 1860.

The first of these rulers was Fakhr-al-Din, a Druze feudal lord who ruled from 1585 to 1635. The Druze constituted one of the major confessional groups in Lebanon. They had emerged from Egypt during the eleventh century, synthesizing Eastern ideas about reincarnation with Islamic and Hellenic thought. Unlike the Maronites, who were considered second-class citizens under Ottoman rule, the Druze enjoyed full civil rights, although they too were not universally accepted in the Muslim world.

Fakhr-al-Din, realizing the economic and political potential associated with cultivating Maronite links with Europe through their historical connections with Rome, granted them full civil liberty and religious freedom. He was thus able to pursue his own ambitions, commanding, for the first time in Lebanese history, a united front of Christian and Druze leaders. At the same time, a wave of westernization swept the country, with European merchants and technicians bringing their skills to the feudal country. Fakhr-al-Din’s policies also paved the way for a more integrated society, with the hitherto segregated Maronites of the north migrating southward, and Fakhr-al-Din came to be considered “the first modern man of Lebanon.”17

The second influential ruler was Bashir II, who came in and out of power between 1788 and 1840. By the beginning of the nineteenth century European influence had already penetrated into the Arab world. In 1798 Napoleon had captured Egypt, bringing with him cherished Western ideals such as social justice, the scientific method, and individual liberty. However, Napoleon compromised such ideals of the French Enlightenment in favor of building French imperialistic glory. Along with the European invasion came missionaries whose aim was to spread their own particular faith which they believed to be the only true one – although they did contribute significantly to society in the building of schools, hospitals, and clinics. However, bitter theological disputes and controversies erupted, instigated by the very people who purported to preach the gospel of love. As a consequence, the gulf between Christians, Muslims, and Druze widened, as did divisions between the various Christian communities.

Under Bashir II a second period of westernization began. Machinery and modern engineering were introduced and new roads were built connecting the villages with the coast and its ports. In 1820 the Turkish overlords demanded extra levels of taxation. Bashir, not wishing to offend the Druze, demanded more tax from the Maronites. This led to the emergence in the 1820s of a peasants’ movement known as the General Uprising. Over the years, some of the Maronite hierarchy – its metropolitans and bishops – had become worldly, greedy, and corrupt as their secular power had increased. The General Uprising, organized by Maronite priests and monks, openly challenged entrenched privilege, both feudal and ecclesiastical. Although Bashir managed to outmaneuver the peasants, the egalitarian ideals espoused were firmly sown in the consciousness of a new generation, and later inspired Gibran in his early Arabic writings.

Westernization, meanwhile, led to the emergence in the towns of wealthy middle-class Christian communities who controlled commerce and industry. The Druze, untouched by progressive influence, were easily exploited by their leaders, who, desiring to fulfill their own ambitions, encouraged and fueled sectarianism whenever possible. Thus arose the confused situation in which economic and political unrest could not be distinguished from religious strife, and in which the latter, combined with feudalism, was ultimately able to derail the country from its path toward progress.

Hoping to capitalize on the growing unrest, the European powers – who were greedily competing for the spoils of a disintegrating Ottoman empire – cynically promoted bloody civil war in Lebanon. The Ottomans themselves also encouraged division and enmity, believing that ultimately their own self-interests would be furthered. The Western powers availed themselves of pretexts for intervention, thus furthering their own expansionist policies. The Maronites looked to France for protection; the Greek Orthodox to Russia for patronage; and the non-Christian communities, including the Druze, enjoyed the support of Britain, which, on the whole, played the role of the sultan’s friend in order to forestall French and Russian ambitions in the region.

When the growing mistrust flared into open hostility in 1845, the Ottoman policy was to aid the Druze by promising the fleeing Christians safe haven. Disarming them thus, the Druze were free to butcher them, young and old together.18 In one period, lasting less than four weeks during 1860, an estimated eleven thousand Christians were killed. The Protestant missionaries and their converts, antagonistic to the Maronites and Orthodox, were not a threat to the Druze, Ottoman, or Muslim authorities, and largely escaped the persecution.

During this destruction the villagers of Bisharri relied on their ancient instinct for survival and retreated to the impregnable fortress of the mountain. Even though Gibran’s father escaped the bloodshed, the stories and haunting memories of his older relatives remained in the poet’s mind all his life. In Spirits Rebellious, published forty-eight years after the mas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Beginnings (1883–1895)

- 2 The New World (1895–1898)

- 3 Returning to the Roots (1898–1902)

- 4 Overcoming Tragedy (1902–1908)

- 5 The City of Light (1908–1910)

- 6 The Poet-Painter in Search (1910–1914)

- 7 The Madman (1914–1920)

- 8 A Literary Movement is Born (1920)

- 9 A Strange Little Book (1921–1923)

- 10 The Master Poet (1923–1928)

- 11 The Return of the Wanderer (1929–1931)

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index