- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Twenty years after Stephen Hawking's 9-million-copy selling A Brief History of Time, pioneering theoretical physicist Sean Carroll takes our investigation into the nature of time to the next level. You can't unscramble an egg and you can't remember the future. But what if time doesn't (or didn't!) always go in the same direction? Carroll's paradigm-shifting research suggests that other universes experience time running in the opposite direction to our own. Exploring subjects from entropy and quantum mechanics to time travel and the meaning of life, Carroll presents a dazzling new view of how we came to exist.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Time, Experience, and the Universe

1

The Past Is Present Memory

The Past Is Present Memory

What is time? If no one asks me, I know. If I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.

—St. Augustine, Confessions

The next time you find yourself in a bar, or on an airplane, or standing in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles, you can pass the time by asking the strangers around you how they would define the word time. That’s what I started doing, anyway, as part of my research for this book. You’ll probably hear interesting answers: “Time is what moves us along through life,” “Time is what separates the past from the future,” “Time is part of the universe,” and more along those lines. My favorite was “Time is how we know when things happen.”

All of these concepts capture some part of the truth. We might struggle to put the meaning of “time” into words, but like St. Augustine we nevertheless manage to deal with time pretty effectively in our everyday lives. Most people know how to read a clock, how to estimate the time it will take to drive to work or make a cup of coffee, and how to manage to meet their friends for dinner at roughly the appointed hour. Even if we can’t easily articulate what exactly it is we mean by “time,” its basic workings make sense at an intuitive level.

Like a Supreme Court justice confronted with obscenity, we know time when we see it, and for most purposes that’s good enough. But certain aspects of time remain deeply mysterious. Do we really know what the word means?

What we mean by time

The world does not present us with abstract concepts wrapped up with pretty bows, which we then must work to understand and reconcile with other concepts. Rather, the world presents us with phenomena, things that we observe and make note of, from which we must then work to derive concepts that help us understand how those phenomena relate to the rest of our experience. For subtle concepts such as entropy, this is pretty clear. You don’t walk down the street and bump into some entropy; you have to observe a variety of phenomena in nature and discern a pattern that is best thought of in terms of a new concept you label “entropy.” Armed with this helpful new concept, you observe even more phenomena, and you are inspired to refine and improve upon your original notion of what entropy really is.

For an idea as primitive and indispensable as “time,” the fact that we invent the concept rather than having it handed to us by the universe is less obvious—time is something we literally don’t know how to live without. Nevertheless, part of the task of science (and philosophy) is to take our intuitive notion of a basic concept such as “time” and turn it into something rigorous. What we find along the way is that we haven’t been using this word in a single unambiguous fashion; it has a few different meanings, each of which merits its own careful elucidation.

Time comes in three different aspects, all of which are going to be important to us.

| 1. | Time labels moments in the universe. |

| | Time is a coordinate; it helps us locate things. |

| 2. | Time measures the duration elapsed between events. |

| | Time is what clocks measure. |

| 3. | Time is a medium through which we move. |

| | Time is the agent of change. We move through it, or—equivalently—time flows past us, from the past, through the present, toward the future. |

At first glance, these all sound somewhat similar. Time labels moments, it measures duration, and it moves from past to future—sure, nothing controversial about any of that. But as we dig more deeply, we’ll see how these ideas don’t need to be related to one another—they represent logically independent concepts that happen to be tightly intertwined in our actual world. Why that is so? The answer matters more than scientists have tended to think.

1. Time labels moments in the universe

John Archibald Wheeler, an influential American physicist who coined the term black hole, was once asked how he would define “time.” After thinking for a while, he came up with this: “Time is Nature’s way of keeping everything from happening at once.”

There is a lot of truth there, and more than a little wisdom. When we ordinarily think about the world, not as scientists or philosophers but as people getting through life, we tend to identify “the world” as a collection of things, located in various places. Physicists combine all of the places together and label the whole collection “space,” and they have different ways of thinking about the kinds of things that exist in space—atoms, elementary particles, quantum fields, depending on the context. But the underlying idea is the same. You’re sitting in a room, there are various pieces of furniture, some books, perhaps food or other people, certainly some air molecules—the collection of all those things, everywhere from nearby to the far reaches of intergalactic space, is “the world.”

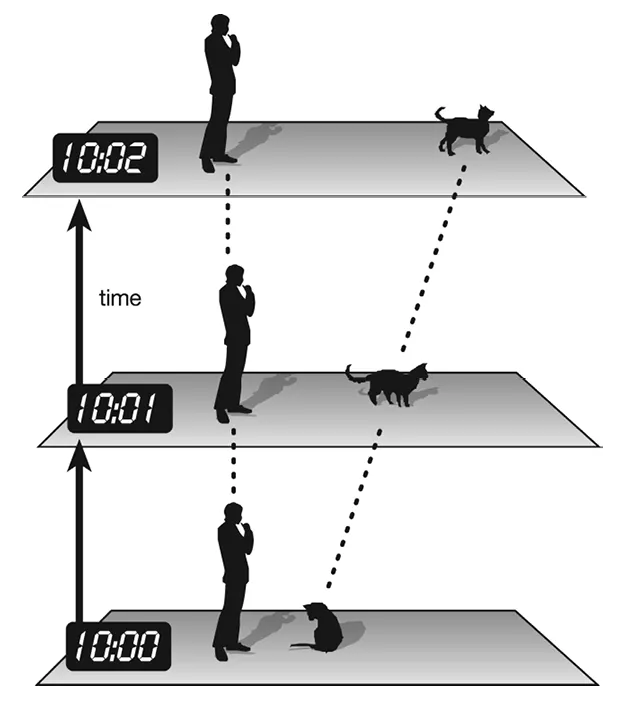

And the world changes. We find objects in some particular arrangement, and we also find them in some other arrangement. (It’s very hard to craft a sensible sentence along those lines without referring to the concept of time.) But we don’t see the different configurations “simultaneously,” or “at once.” We see one configuration—here you are on the sofa, and the cat is in your lap—and then we see another configuration—the cat has jumped off your lap, annoyed at the lack of attention while you are engrossed in your book. So the world appears to us again and again, in various configurations, but these configurations are somehow distinct. Happily, we can label the various configurations to keep straight which is which—Miss Kitty is walking away “now”; she was on your lap “then.” That label is time.

So the world exists, and what is more, the world happens, again and again. In that sense, the world is like the different frames of a film reel—a film whose camera view includes the entire universe. (There are also, as far as we can tell, an infinite number of frames, infinitesimally separated.) But of course, a film is much more than a pile of individual frames. Those frames better be in the right order, which is crucial for making sense of the movie. Time is the same way. We can say much more than “that happened,” and “that also happened,” and “that happened, too.” We can say that this happened before that happened, and the other thing is going to happen after. Time isn’t just a label on each instance of the world; it provides a sequence that puts the different instances in order.

Figure 1: The world, ordered into different moments of time. Objects (including people and cats) persist from moment to moment, defining world lines that stretch through time.

A real film, of course, doesn’t include the entire universe within its field of view. Because of that, movie editing typically involves “cuts”—abrupt jumps from one scene or camera angle to another. Imagine a movie in which every single transition between two frames was a cut to a completely different scene. When shown through a projector, it would be incomprehensible—on the screen it would look like random static. Presumably there is some French avant-garde film that has already used this technique.

The real universe is not an avant-garde film. We experience a degree of continuity through time—if the cat is on your lap now, there might be some danger that she will stalk off, but there is little worry that she will simply dematerialize into nothingness one moment later. This continuity is not absolute, at the microscopic level; particles can appear and disappear, or at least transform under the right conditions into different kinds of particles. But there is not a wholesale rearrangement of reality from moment to moment.

This phenomenon of persistence allows us to think about “the world” in a different way. Instead of a collection of things distributed through space that keep changing into different configurations, we can think of the entire history of the world, or any particular thing in it, in one fell swoop. Rather than thinking of Miss Ki...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- PART ONE: TIME, EXPERIENCE, AND THE UNIVERSE

- 1 The Past Is Present Memory

- 2 The Heavy Hand of Entropy

- 3 The Beginning and End of Time

- PART TWO: TIME IN EINSTEIN’S UNIVERSE

- 4 Time Is Personal

- 5 Time Is Flexible

- 6 Looping through Time

- PART THREE: ENTROPY AND TIME’S ARROW

- 7 Running Time Backwards

- 8 Entropy and Disorder

- 9 Information and Life

- 10 Recurrent Nightmares

- 11 Quantum Time

- PART FOUR: FROM THE KITCHEN TO THE MULTIVERSE

- 12 Black Holes: The Ends of Time

- 13 The Life of the Universe

- 14 Inflation and the Multiverse

- 15 The Past Through Tomorrow

- 16 Epilogue

- Appendix: Maths

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access From Eternity to Here by Sean Carroll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Physics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.