This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

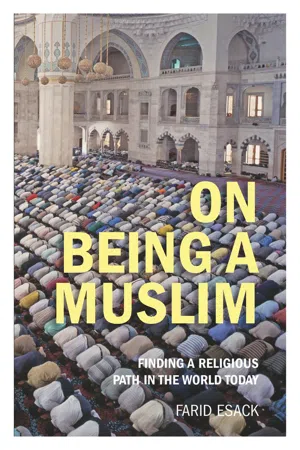

A personal account of Muslim life in the modern world and the trials it raises Funny, challenging, controversial, passionate and unforgiving, this is an unprecedented personal account of a Muslim's life in the modern world. A perceptive ground-breaking account of modern Islam, there is a great deal to be learnt from this book by anyone interested in the burning social and spiritual issues of the day.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access On Being a Muslim by Farid Esack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Teología islámica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teología y religiónSubtopic

Teología islámicaONE

on being with Allah

And if My servants ask you about Me – behold, I am near; I respond to the call of the one who calls whenever he calls unto Me; let them then respond unto me and believe in Me; so that they may be guided.

Qur’an 2:186

Belief in the existence and unity of Allah, the Transcendent, is central to the life of a Muslim and the Qur’an places much emphasis on cultivating a relationship with Allah as a living and caring God to whom all humankind will return and to whom we are all accountable. The presence of Allah in the world and ultimate accountability to Him1 are absolute assumptions for virtually all Muslims. I say, ‘virtually all’ because, notwithstanding theological definitions of a ‘muslim’,2 the ummah (universal community of Muslims) is not without its children who have, unannounced, walked away from their faith in Allah while holding on to many of the cultural trappings of the religious community of Muslims.

Most Muslims experience and give expression to this faith in Allah through a range of religious practices and verbal utterances, and in the way in which they seek refuge in the ultimate when personal, natural or social calamities strike. Others, equally sincere, are desperate actually to make sense of the presence of Allah in a world where, seemingly, evil so often triumphs over good. While a religious life filled only with rituals may be meaningful for some, many others whose faith is in search of integrity cannot avoid the questions thrown up by being alive to the world and all its challenges.

The Sufi tradition in Islam, acknowledging the limitations of religious life confined to ideology, laws and rituals, is one that has made a vibrant relationship with Allah and leading a God-conscious life the centre of its quest. Despite the seeming preponderance of the somewhat colder face of Islam, the vast majority of ordinary believers throughout the world still revere much of the Sufi tradition. At the most widely practised level, though, this has regrettably been reduced to a new set of folk rituals, with a focus on saints and other holy men as the primary means of reaching closeness to the Prophet (Peace be upon him), who is expected to intercede with Allah.

Our lives as Muslims are largely devoid of an ongoing and living connection with Allah. We confine this relationship to moments of personal difficulty, have it mediated through a professional class of religious figures – the managers of the sacred – or to the formal rituals of the five daily prayers, the pilgrimage to Mecca and fasting in the month of Ramadan. Absent is the warmth evident from the following hadith qudsi (a saying of Allah, in the words of the Prophet):

When a servant of Mine seeks to approach Me through that which I like out of what I have made obligatory upon him [her] and continues to advance towards Me through voluntary effort beyond the prescribed, then I begin to love him [her]. When I Love him [her] I become the ears by which [s]he hears, the eyes by which [s]he sees, and the hands by which [s]he grasps, and the feet with which [s]he walks. When [s]he asks Me I bestow upon him [her] and when [s]he seeks My protection, I Protect him [her].3

Given the emphasis on this relationship in the Qur’an, and the insistence that Allah is the focus of a believer’s life, most of this chapter deals with this relationship rather than the rituals which serve as the means to cultivate and express it.

The chapter starts with a rather personal account of wrestling with the presence of Allah during a visit to Mecca, and then deals with the way we often project our ‘selves’ on to Allah, and how we end up really seeing mirror images of our often ugly selves. The struggle for an authentic spirituality accompanied by righteous works and the need to avoid simplistic answers is then discussed.

Besides the pilgrimage to Mecca, the other two acts of devotion that virtually every Muslim is obliged to fulfil are the five daily prayers and the fast of the month of Ramadan. The last part of this chapter considers some of the challenges presented by these and suggests ways in which they can become more meaningful.

The relationship with Allah dealt with in this chapter is often uncomfortable, and I discuss it in the full awareness that many of us prefer to bury this discomfort. Despite the occasional funny or even flippant twist to my narratives, I do not regard this discomfort or wrestling with Allah lightly. I do, however, believe that in my own uttering of it I develop a deeper insight into it. In so doing, others may also understand their struggles a bit better. Hopefully, we can all respond in ways that take us closer to Allah.

CAN ALLAH BE SUPREMELY INDIFFERENT?

‘Is Allah?’, ‘Is Allah a He?’, ‘Is He all powerful?’, ‘If He is all powerful can He make a stone so heavy that He is unable to move it?’, ‘Where is Allah?’, ‘Is He omnipresent?’, ‘If one takes everything that exists in the heaven and the earth and calls it “the whole”, then that would also include Allah, wouldn’t it?’ ‘Well, if that is the case, then is He smaller than “the whole”?’, ‘If He is, then will He still be Allah?’ These are the kinds of questions that have dabbled with me since I was a kid.

They’re OK, possibly even funny to some. If, however, you look at a three-year-old child dying of Aids and you also believe in an All-Powerful God, then the questions take a more serious turn. ‘If He is, then why the silence in the face of suffering?’ If Allah is a He then what does it say at the end of the day about the worth of the theological gymnastics that gender-sensitive Muslims engage in to make their Islam more palatable?

Many years ago a friend, Ashiek, who regularly questioned me on matters of faith, told me: ‘Farid, I often feel that you answer me well, but that that answer is meant for me and that you yourself are far from satisfied with it.’ I’ve come a little further in my quest for honesty since then and, mercifully, have stopped viewing myself as an answering machine.

Many of us who do take Allah seriously have been desperate for answers to questions that tear at our selves, and do not understand why He watches us being destroyed by the absence of answers. How often have I not screamed at Allah: ‘Do something!’ (And as Nader, citing an anonymous source, tells me: ‘I once heard a young man screaming at God for letting young children starve until he realized the starving children were God screaming at him for letting it happen.’)

You have said: ‘These are the days that we interspersed in between (the lives) of humankind that Allah may know those who [truly] believe and those among you who take witnesses [besides Him]’ (Q. 3:140). OK, so now you have caught me out as ‘one who takes witnesses besides you’. Oh no, I never bowed in front of an idol but there are many other gods – academic ladders, sex, power, prestige. ‘So, here I am in front of you, I, a lousy hypocrite; so do something! Don’t just leave me like this!’ How often have I not stood in Medina at the grave of Muhammad, our shepherd and, like a lost sheep, begged to be found and returned to the flock?

Here follows my narration of one such encounter with Allah, who, at that time, appeared to be the Supremely Indifferent. It was in Mecca, the ‘Mother of Cities’ and the place that houses the Ka‘bah, the small black cloth-covered cube-shaped construction referred to in the Qur’an as the ‘first house determined for humankind’ (Q. 3:96). For Muslims, a visit to Mecca is often the fulfilment of a lifelong dream. For some, as my story shows, the rewarding consequences and fulfilment coming from such a visit are often obscured and delayed.

Pepsi Shows the Way4

Mecca is referred to in the Qur’an as the ma‘ad, the place of return (Q. 28:85). I had undertaken my first journey there some years ago and it was meant to be a journey ‘home’ before the ultimate journey ‘home’ (the Qur’an also describes all of life as part of this return to Allah, e.g., Q. 2:285; 3:38). For Muslims, a journey to Mecca is also an encounter with our roots; genealogical, religious and spiritual. It is in some ways a return to our genealogical roots because Adam and Eve (Peace be upon them) dwelt on the plains of the Mountain of ‘Arafah, located there, after their departure from Paradise. It is a return to our religious roots because the Cave of Hira’, where the Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him) encountered his first revelation, is the physical point of the beginning of Islam as a religion. Lastly, it is a return to our spiritual roots, because the Ka‘bah is the symbol of the presence of Allah, the House of Allah.

I approached Mecca with a mixture of feelings. Social conditioning: the many tales of experiences of ‘hearts overflowing’ told by returning pilgrims compelling me to just ‘feel the greatness of the moment’; my secular disposition militating against this and beckoning me to be calm; the nafs al-lawwamah (berating self) mockingly chiding: ‘Are you not ashamed of defiling the sacred soil of Mecca with your footprints?’ Anyway, the journey had cost a good few hundred dollars and no taunts from a berating self were going to make me turn back.

One actually descends into the haram (sacred area) from the barren surrounding hills. And here the Ka‘bah rose in its full majesty and glory. If only I, too, I thought, could descend into a seemingly barren self and cause a new being to come forth from a desolate soul. As Muhammad Iqbal, the Pakistani poet, said: ‘Re-chisel then your ancient frame and build up a new being – such being, being real being, or else your ego is a mere ring of smoke.’ I hoped again for the first time in many years. If this land in its barrenness can become the spring where so much of humankind come to be nourished, then there must be hope. A spring can yet flow from my existence of seeming nothingness and allow me to drink from it, so that I may become fully human and fully Muslim.

Clad in ihram, the simple two-piece cotton wrapping worn by all pilgrims, a money bag tied to my waist, my soul tied to the travellers’ cheques and my physical body to my passport therein, I joined the multitude in approaching the bait al-atiq (ancient house). I became lost in the crowd. Is there then just no limit to the times that one can get lost? Getting lost to intellectual jargon, hobbies, organizations, causes, one’s family, even to one’s self? Will I ever be found and returned to ‘its rightful owner’? Just this once – answer me! I won’t ask any more questions after this! (Silence.)

Clinging to my booklet of du’as (prayers) I hurriedly completed the seven tawafs (circumambulations) around the Ka‘bah, dutifully reciting the prescribed du’a for each particular round. However desperately needed, there was still no self-expression or erratic, even frenzied, crying from a mutilated self. Was my soul the victim of a conspiracy between the ‘ulama (clergy) and that book vendor who sold me this collection of prescribed litanies? Was the written word again going to be the separating wall between me and my Sustainer? Was the eternal alliance between religion and capitalism being replayed here, destroying the innocent and vulnerable?

I was desperate to get the preliminaries over before reaching the Hajar-al-Aswad (Black Stone), a stone reportedly from heaven and placed in that spot by Muhammad, and then ultimately the multazam, the door of the Ka‘bah. Before I knew it, my first set of circumambulations around the Ka‘bah was complete – the first part of an emptying process, a burning out while rotating around the candle before being consumed by the flame. (Was I also following the advice of Jalal al-Din Rumi, who said: ‘die before you die’, even as I was returning to my place of return, Mecca, before my ultimate return to my Lord?)

I elbowed my way to the Black Stone, fervently hoping that it might absorb my blackness (this was long before I wondered about the equation of sin with blackness), my burdensome title, power games, politico-religious position, eloquence and mess-ups. And then, still clinging to my book of litanies, money bag and passport, I reached the door. Somewhere, something arose from deep within me to destroy the conspiracy between the book vendor and the clergy which demanded that I respond from a prescribed text, and between the modernists and capitalists which demanded that I ‘control my emotions’. Temporarily liberated, I lowered my small book and my orderly litanies gave way to uncontrolled weeping. And I remembered the anecdotes of returning South African pilgrims: ‘Oh, you should have seen how the poor Pakistanis clung to the cloth of the Ka‘bah; it was a sight for sore eyes.’ I sobbed and only remember choking in a single expression: ‘humiliated in Your presence’. For once, I was happy to be a ‘poor Pakistani’.

There were others, too, who sobbed, but this was one time when a person wrapped up in him or herself didn’t make a nasty little bundle; I was at His door. I wept bitterly, for my past, present and future, I wept for what I believed was an existence in mud and actually hoped that someone would come from inside the door. For a Muslim, there is no physical point, ‘defiled’ as he or she may be, beyond that door and there I had reached. The burden of that moment was shattering.

As if that wasn’t enough . . . The silence that greeted me was deafening in its loudness. There was no glimmer of the emergence of a new being after being consumed by the flame. I sat there, drained and frightened, after what appeared to be hours of choking in ‘humiliated in Your presence’. With my emptiness and nothingness complete, I stumbled away, repeating to myself: ‘What did He have in mind to subject me to this apparently divine indifference?’

Much later, a body returned to complete the obligatory two raka‘at (prayer units) at the Maqam al-Mahmud, the place where Abraham (Peace be upon him) is said to have prayed (Q. 2:125). A body went to drink from the sacred Zam Zam well, a body went to run between the hills of Saffa and Marwah in imitation of Hagar (Peace be upon her), the Black wife of Abraham, a body went to the hotel, a body returned to the haram five times a day for three days and a body got on to a bus which dropped it at the foot of the Mount of Light.

It was on this mountain that the Prophet Muhammad’s anguished heart found solace through revelation, after being shattered. And who knows? I can always take a try. Anyway, I had nothing to lose. Being in the heart of summer, and midday at that, there were no other bodies or souls around. Seven-year-old Musa looked at me quizzically for a few seconds before venturing to ask: ‘Are you sure you don’t want to wait till it is cooler?’ ‘Musa! Unlike your namesake in the Qur’an, I am not looking for a match or wood or fire. There is no flock awaiting me. I am alone and this journey is a matter of life and death for me. I want the mountain to be abandoned when I make my discovery. Musa, surely you understand all about these mountain trips?’ The poor kid looked at me as if I was potty. (Not that he was very far off the mark, mind you.) I paid him for my bottle of spring water and started the ascent to the Cave of Hira’.

The Saudi regime, being very ‘puritanical’ and vehemently opposed to any form of ‘unorthodox’ veneration, does not encourage visits to any of the traditional sacred places. There are, thus, no official signs showing the path to the Cave of Hirah. You’ve got to follow the people. And if there are none around? Follow the Pepsi cans! Thousands and thousands of them, all along the route right up to the mouth of the cave, a few even littering its interior. What a sad spectacle! Along comes this ‘follower’ of Muhammad, his soul tied to Cook’s American Dollar travellers’ cheques, following a Pepsi-littered path and he says he is searching for Truth! Why don’t you try another one, ‘follower’ of Muhammad?

Let me not be unfair to attempts by Muslims to outline the path for themselves. There were a few shoddily painted arrows pointing in the same direction as the Pepsi cans. Whatever little use these attempts to ‘outline the path’ may have been, was neutralized by the fact that there, in the same paint, in the same shoddy manner, were arrows pointing to exactly opposite directions! As if my agony at having to exorcize a thousand devils was not enough! As if having sheets of plastic ripped off the heads of our people at five o’clock on a cold winter morning in apartheid South Africa was not enough! As if having to mix sand with flour and feeding our children with it was not enough!5 As if two billion people going to bed on the floor or straw or dust at night, on empty stomachs, was not enough! As if . . . And now, arrows pointing in opposite directions!

I continued following the Pepsi cans.

The path was steep and the journey agonizin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. On Being with Allah

- 2. On Being with Myself

- 3. On Being with You

- 4. On Being a Social Being

- 5. On Being with The Gendered Other

- 6. On The Self in a World of Otherness

- 7. On Being a New South African Muslim

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index