CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

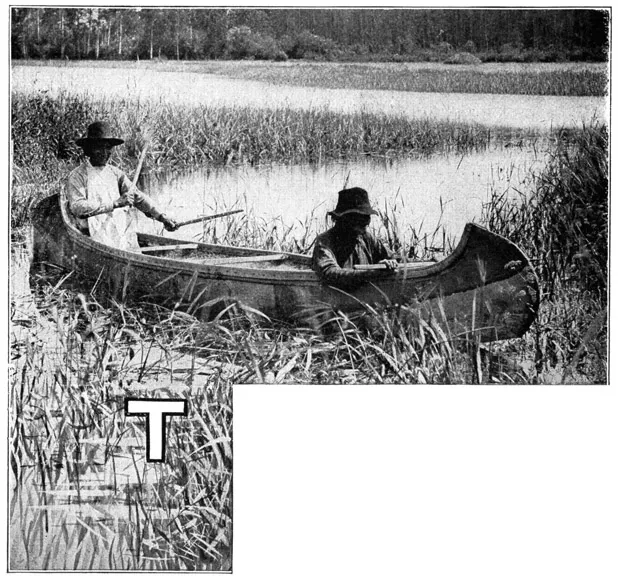

INDIANS GATHERING WILD RICE, N. MINNESOTA

THE home of primeval man was by the waterside. The springs quenched his thirst. The bays afforded his most dependable supply of animal food. Streamhaunting, furbearing animals furnished his clothing. The rivers were his highways. Water sports were a large part of his recreation; and the glorious beauty of mirroring surfaces and green flower-decked shores were the manna of his simple soul.

The circumstances of modern life have largely removed mankind from the waterside, and common needs have found other sources of supply; but the primeval instincts remain. And where the waters are clean, and shores unspoiled, thither we still go for rest, and refreshment. Where fishes leap and sweet water lilies glisten, where bull frogs boom and swarms of May-flies hover, there we find a life so different from that of our usual surroundings that its contemplation is full of interest. The school boy lies on the brink of a pool, watching the caddisworms haul their lumbering cases about on the bottom, and the planctologist plies his nets, recording each season the wax and wane of generations of aquatic organisms, and both are satisfied observers.

The study of water life, which is today the special province of the science of limnology*, had its beginning in the remote unchronicled past. Limnology is a modem name; but many limnological phenomena were known of old. The congregating of fishes upon their spawning beds, the emergence of swarms of May-flies from the rivers, the c10udlike flight of midges over the marshes, and even the “water bloom” spreading as a filmy mantle of green over the still surface of the lake—such things could not escape the notice of the most casual observer. Two of the plagues of Egypt were limnological phenomena; the plague of frogs, and the plague of the rivers that were turned to blood.

Such phenomena have always excited great wonderment. And, being little understood, they have given rise to most remarkable superstitions.† Little real knowledge of many of them was possible so long as the most important things involved in them—often even the causative organisms—could not be seen. Progress awaited the discovery of the microscope.

The microscope opened a new world of life to human eyes—“the world of the infinitely small things.” It revealed new marvels of beauty everywhere. It dis covered myriads of living things where none had been suspected to exist, and it brought the elements of organic structure and the beginning processes of organic development first within the range of our vision. And this is not all. Much that might have been seen with the unaided eye was overlooked until the use of the microscope taught the need of closer looking. It would be hard to overestimate the stimulating effect of the invention of this precious instrument on all biological sciences.

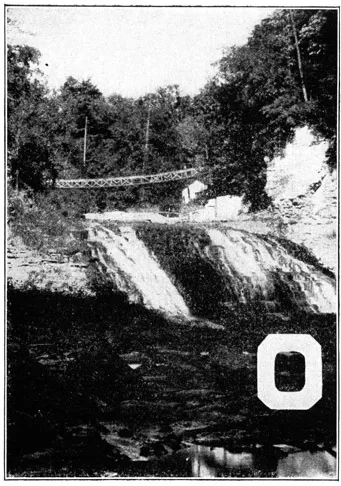

FIG. 1. Waterbloom (Euglena) on the surface film of the Renwick lagoon at Ithaca. The clear streak is the wake of a boat just passed.

With such crude instruments as the early microscopists could command they began to explore the world over again. They looked into the minute structure of everything—forms of crystals, structure of tissues, scales of insects, hairs and fibers, and, above all else, the micro-organisms of the water. These, living in a transparent medium, needed only to be lifted in a drop of water to be ready for observation. At once the early microscopists became most ardent explorers of the water. They found every ditch and stagnant pool teeming with forms, new and wonderful and strange. They often found each drop of water inhabited. They gained a new conception of the world’s fulness of life and one of the greatest of them Roesel von Rosenhof, expressed in the title of his book, “Insekten Belustigung”* the pleasure they all felt in their work. It was the joy of pioneering. Little wonder that during a long period of exploration microscopy became an end in itself. Who that has used a microscope has not been fascinated on first acquaintance with the dainty elegance and beauty of the desmids, the exquisite sculpturing of diatom shells, the all-revealing transparency of the daphnias, etc., and who has not thereby gained a new appreciation of the ancient saying, Natura maxime miranda in minimis.†

Among these pioneers there were great naturalists—Swammerdam and Leeuwenhoek in Holland, the latter, the maker of his own lenses; Malpighi and Redi in Italy; Reaumer and Trembly in France; the above mentioned, Roesel, a German, who was a painter of miniatures; and many others. These have left us faithful records of what they saw, in descriptions and figures that in many biological fields are of more than historical importance. These laid the foundations of our knowledge of water life. Chiefly as a result of their labor there emerged out of this ancient “natural philosophy” the segregated sciences of zoology and botany. Our modem conceptions of biology came later, being based on knowledge which only the perfected microscope could reveal.

A long period of pioneer exploration resulted in the discovery of new forms of aquatic life in amazing richness and variety. These had to be studied and classified, segregated into groups and monographed, and this great survey work occupied the talents of many gifted botanists and zoologists through two succeeding centuries—indeed it is not yet completed. But about two centuries after the construction of the first microscope, occurred an event of a very different kind, that was destined to exert a profound influence throughout the whole range of biology. This was the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species. This book furnished also a tool, but of another sort—a tool of the mind. It set forth a theory of evolution, and offered an explanation of a possible method by which evolution might come to pass, and backed the explanation with such abundant and convincing evidence that the theory could no longer be ignored or scoffed out of court. It had to be studied. The idea of evolution carried with it a new conception of the life of the world. If true it was vastly important. Where should the evidence for proof or refutation be found? Naturally, the simpler organisms, of possible ancestral characteristics, were sought out and studied, and these live in the water. Also the simpler developmental processes, with all they offer of evidence; and these are found in the water. Hence the study of water life, especially with regard to structure and development. received a mighty impetus from the publication of this epoch-making book. The half century that has since elapsed has been one of unparalleled activity in these fields.

Almost simultaneously with the appearance of Darwin’s great work, there occurred another event which did more perhaps than any other single thing to bring about the recognition of the limnological part of the field of biology as one worthy of a separate recognition and a name. This was the discovery of plancton—that free-floating assemblage of organisms in great water masses, that is self-sustaining and self-maintaining and that is independent of the life of the land. Liljeborg and Sars found it, by drawing fine nets through the waters of the Baltic. They found a whole fauna and flora, mostly microscopic—a well adjusted society of organisms, with its producing class of synthetic plant forms and its consuming class of animals; and among the animals, all the usual social groups, herbivores and carnivores, parasites and scavengers. Later, this assemblage of minute free-swimming organisms was named plancton.* After its discovery the seas could no longer be regarded as “barren wastes of waters”; for they had been found teeming with life. This discovery initiated a new line of biological exploration, the survey of the life of the seas. It was simple matter to draw a fine silk net through the open water and collect everything contained therein. There are no obstructions or hiding places, as there are everywhere on land; and the fine opportunity for quantitative as well as qualitative determination of the life of water areas was quickly grasped. The many expeditions that have been sent out on the seas and lakes of the world have resulted in our having more accurate and detailed knowledge of the total life of certain of these waters than we have, or are likely to be able soon to acquire, of life on land.

Prominent among the investigators of fresh water life in America during the nineteenth century were Louis Agassiz, an inspiring teacher, and founder of the first of our biological field stations; Dr. Joseph Leidy, an excellent zoologist of Philadelphia, and Alfred C. Stokes of New Jersey, whose Aquatic Microscopy is still a useful handbook for beginners.

Our knowledge of aquatic life has been long accumulating. Those who have contributed have been of very diverse training and equipment and have employed very different methods. Fishermen and whalers; collectors and naturalists; zoologists and botanists, with specialists in many groups; water analysts and sanitarians; navigators and surveyors; planktologists and bacteriologists, and biologists of many names and sorts and degrees; all have had a share. For the water has held something of interest for everyone.

Fishing is one of the most ancient of human occupations; and doubtless the beginning of this science was made by simple fisher-folk. Not all fishing is, or ever has been, the catching of fish. The observant fisherman has ever wished to know more of the ways of nature, and science takes its origin in the fulfillment of this desire.

The largest and the smallest of organisms live in the water, and no one was ever equipped, or will ever be equipped to study any considerable part of them. Practical difficulties stand in the way. One may not catch whales and water-fleas with the same tackle, nor weigh them upon the same balance. Consider the difference in equipment, methods, area covered and numbers caught in a few typical kinds of aquatic collecting:

(1). Whaling involves the coöperative efforts of many men possessed of a specially equipped vessel. A single specimen is a good catch and leagues of ocean may have to be traversed in making it.

(2). Fishing may be done by one person alone, equipped with a hook and line. An acre of water affords area enough and ten fishes may be called a good catch.

(3). Collecting the commoner invertebrates, such as water insects, crustaceans and snails involves ordinarily the use of a hand net. A square rod of water is sufficient area to ply it in; a satisfactory catch may be a hundred specimens.

(4). For collecting entomostracans and the larger plancton organisms towing nets of fine silk bolting-cloth are commonly employed. Possibly a cubic meter of water is strained and a good catch of a thousand specimens may result.

(5). The microplancton organisms that slip through the meshes of the finest nets are collected by means of centrifuge and filter. A liter of water is often an ample field for finding ten thousand specimens.

(6). Last and least are the water bacteria, which are gathered by means of cultures. A single drop of water will often furnish a good seeding for a culture plate yielding hundreds of thousands of specimens.

Thus the field of operation varies from a wide sea to a single drop of water and the weapons of chase from a harpoon gun to a sterilized needle. Such divergencies have from the beginning enforced specialization among limnological workers, and different methods of studying the problems of water life have grown up wide apart, and, often, unfortunately, without mutual recognition. The educational, the economic and the sanitary interests of the people in the water have been too often dealt with as though they are wholly unrelated.

The agencies that in America furnish aid and support to investigations in fresh water biology are in the main:

1. Universities which give courses of instruction in limnology and other biological subjects, and some of which maintain field stations or laboratories for investigation of water problems. 2. National, state and municipal boards and surveys, which more or less constantly maintain researches that bear directly upon their own economic or sanitary problems. 3. Societies, academies, institutes, museums, etc., which variously provide laboratory facilities or equip expeditions or publish the results of investigations. 4. Private individuals, who see the need of some special investigation and devote their means to furthering it. The Universities and private benefactors do most to care for the researches in fundamental science. Fish commissions and sanitary commissions support the applied science. Governmental and incorporated institutions assist in various ways and divide the main work of publishing the results of investigations.

It is pioneer limnological work that these various agencies are doing; as yet it is all new and uncorrelated. It is all done at the instance of some newly discovered and pressing need. America has quickly passed from being a wilderness into a state of highly artificial culture. In its centers of population great changes of circumstances have come about and new needs have suddenly arisen. First was felt the failure of the food supply which natural waters furnished; and this lack led to the beginning of those limnological enterprises that are related to scientific fish culture. Next the supply of pure water for drinking failed in our great cities; knowledge of water-borne diseases came to the fore: knowledge of the agency of certain aquatic insects as carriers of dread diseases came in; and suddenly there began all those limnological enterprises that are connected with sanitation. Lastly, the failure of clean pleasure grounds by the water-side, and of wholesome places of recreation for the whole people through the wastefulness of our past methods of exploitation, through stream and lake despoiling, has led to those broader limnological studies that have to do with the conservation of our natural resources.

WATER

OF ALL inorganic substances, acting in their own p...