Introduction

In the early Middle Ages the primary “community of Saint Martin” was the city of Tours. Martin’s cult gave physical shape to the medieval town, whose principal centers of settlement, religious cult, and commercial activity grew up around three churches associated with the saint. More important, however, fifth- and sixth-century bishops of Tours employed Martin’s cult to create an ideal image of the civic community. Tours, the bishops suggested, was Martin’s town, and it was united under the authority of its bishop, who guarded Martin’s cult and inherited his position.

By the beginning of the twelfth century this “community of Saint Martin” no longer existed. Although a number of earlier events chipped away at this idealized civic community, it was above all the monastic exemption movement of the eleventh and twelfth centuries that caused its complete demise. The monks of the abbey of Marmoutier and the canons of the basilica of Saint-Martin succeeded in gaining exemption from the disciplinary and liturgical dominance of their archbishops. As a result, the archbishops’ access to Martin’s cult became severely limited. New legends and liturgical observances underscored this change: Tours became, in the symbolic representations that emanated from Marmoutier and Saint-Martin, two communities. On the one hand, there was the new “community of Saint Martin,” consisting of Marmoutier, Saint-Martin, and the walled suburb of Châteauneuf. And on the other hand, there was the now isolated, and less vibrant, cathedral town.

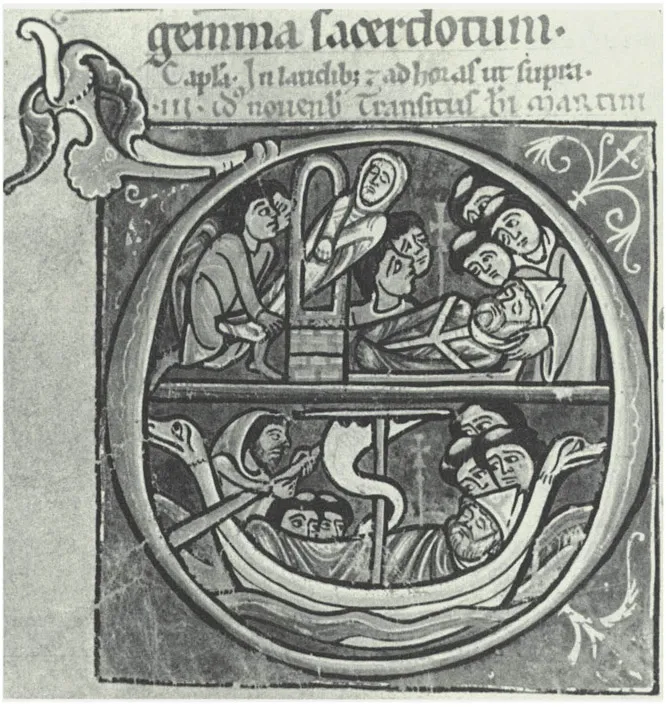

PLATE 1. Saint Martin’s body returns to Tours. “But almighty God would not allow the town of Tours to be deprived of its patron.” So claimed Gregory of Tours when he recounted how the men of Tours stole away from the parish of Candes with Saint Martin’s body while the men of Poitiers, who thought their town had the better claim to the body of the saint, slept. For Gregory this story signified that Martin’s power belonged, in a special way, to the town of Tours.

In the top half of this twelfth-century illumination for the feast of Martin’s death (November 11), the men of Tours pass the saint’s body through a window in Candes (while the Poitevins sleep); in the bottom half the men of Tours sail back to Tours with their prize. Like Gregory of Tours, the canons of Saint-Martin, who produced this illustration, wished to demonstrate that Martin and his power belonged to a particular community. As I argue in chapter 2 and in part 3, however, their definition of the community of Saint Martin differed from Gregory’s. Tours, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS. 193 (late twelfth century), fol. 117. Photograph courtesy Tours, Bibliothèque Municipale.

1 Martinopolis (ca. 371–1050)

While the royal seat of Paris excels in military endeavors and command over nations, and the fertile Beauce enriches Chartres, and Orléans prevails with the privilege of natural qualities and of vines, Martinopolis is second to none of these. She is endowed with gifts that are not nature’s least, and her land is not so much wide and spacious as it is fertile, useful, and accommodating.

(“Commendation of the Province of Touraine” [twelfth century])1

Saint Martin and the Topography of Tours

It was customary in the Middle Ages for an urban commendation to commence by describing the setting of a town—the natural resources of its region, the rivers and lesser towns within its domain.2 Topography, as the author of this twelfth-century text was well aware, can play an important role in the development and economy of a city. The region around Tours—with its fertile plains, vine-covered hills, forests, and rivers—provided abundant resources for the support of the town’s inhabitants, and Tours’s location on the Loire, the major east-west artery in France, promoted the commercial endeavors of local merchants.

But natural resources and geographical location alone do not go far in explaining the history of “Martinopolis.” For this town was, from its inception, a product of human artifice, institutions, and imagination. The Romans had defied geographical logic when in the first century they placed the new town of Caesarodunum on the south bank of the Loire, where several of their roads intersected, rather than on the higher, more defensible land of the north bank. Then in the fourth century they contributed to the survival of the town, which came to be known as Tours, by designating it the capital of the province of the Third Lyonnaise.3

But it was above all the Christian religion, and especially the cult of Saint Martin, that contributed to the survival, the importance, and even the shape of medieval Tours. Like other Roman cities, Tours outlived the empire and perpetuated its institutions because it had become an episcopal town. More important, Martin, who was venerated not only as a saint but also as the apostle to the Gauls, occupied the episcopal see there between about 371 and 397. His relics, which remained in the town, became the most prestigious in Frankish Gaul, attracting the attention of pilgrims and kings.4

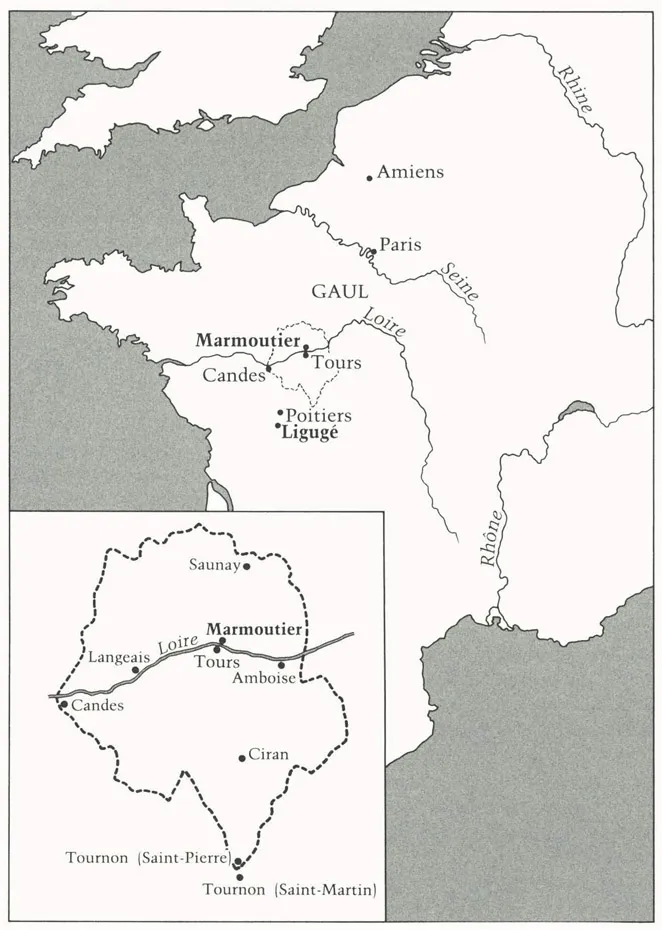

A former Roman soldier who had relinquished his arms to meet the demands of Christianity, Saint Martin remained a man of action throughout his life. Indeed, the landscape of medieval Francia was dotted with the consequences and commemorations of his deeds (see map 1). An oratory near one of the gates of Amiens marked the spot where, as an unbaptized soldier, Martin performed his most famous act of charity, dividing his cape in two and offering half to a beggar. At the northern gate of Paris (on the Ile de la Cité, where the rue Saint-Martin begins) another oratory marked a second act of charity, when Martin cured a leper by kissing him.5

Soon after he left the army Martin founded Ligugé, the first monastery in Gaul. Medieval pilgrims continued to seek cures at this abbey near Poitiers, in the cell where the saint had resuscitated a dead novice. By the twelfth century the monks of Ligugé maintained that the bell in their belfry was the one Martin had used to call his brothers to worship. People suffering from headaches or toothaches found relief by rubbing their afflicted parts against the bell’s rim; striking the bell would dispel lightning and storms.6

MAP 1. The footsteps of Saint Martin, large map: Gaul; inset: diocese of Tours (with parishes founded by Saint Martin, according to Gregory of Tours). Adapted from Fontaine, Sulpice Sévère, vol. 3, following p. 1424.

From Ligugé Martin was called to the bishopric of Tours, where he waged an active war against paganism. In the face of violent opposition, he earned his reputation as apostle to the Gauls by destroying temples and erecting churches throughout his diocese—at Langeais, Saunay, Tournon, Amboise, Ciran, and Candes. Martin died while he was making an episcopal visit to the parish of Candes, which thereby became another center for pilgrims and miracles. In the twelfth century the priests there even claimed to possess a grapevine sprouted from the dried twigs that had served as the dying saint’s bedding. From that vine they produced a wine that they used at the altar and offered to the sick, whose ailments they claimed the wine could cure.7

Clearly, many parts of Francia could exult with the words of the sixth-century poet Fortunatus: “O happy region, to have known the footsteps, look, and touch of the saint!”8 But it was in Tours that Martin resided the longest and had the greatest impact. Ultimately he and his cult even played a fundamental role in influencing the physical form of that town, through the three religious monuments associated with him—the basilica that housed his relics, the abbey he founded, and the cathedral where he served as bishop. According to the thirteenth-century version of the “Commendation of the Province of Touraine,” these were the major institutions of Tours.9 They now formed the nuclei of three distinct sections of the urban conglomerate.

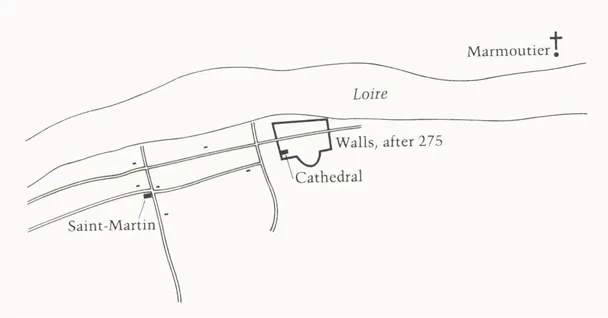

Of course the role that Martin and his cult played in shaping the physical form of medieval Tours was affected by other factors. Both Roman creations and later Germanic and Viking disruptions helped influence where his three institutions were located and how they developed. For example, the cathedral, founded by Litorius, Martin’s predecessor as bishop, was situated, like other cathedrals in Gaul, on the ramparts protecting the administrative center of the Roman town. Hastily erected after Germanic tribes invaded the region sometime around 275, those walls—which continued to define the cathedral town until the twelfth century—reduced the area of Tours to one-quarter of its original size (see map 2).10

MAP 2. Tours, fourth century through sixth century. Adapted from Galinié and Randoin, Archives du sol à Tours, 21.

Roman institutions and later disruptions also influenced the location and development of Martin’s basilica. This was at first a modest church, erected over Martin’s burial place in a Christian cemetery one mile west of the cathedral. The construction of the basilica fit a general pattern: Christians everywhere in the West were building churches over the graves of their dead saints, who had been buried in cemeteries situated—in accordance with Roman prohibitions—outside city walls. Now, however, suburbs took shape around the holy tombs, and the Roman prohibition was abandoned.11

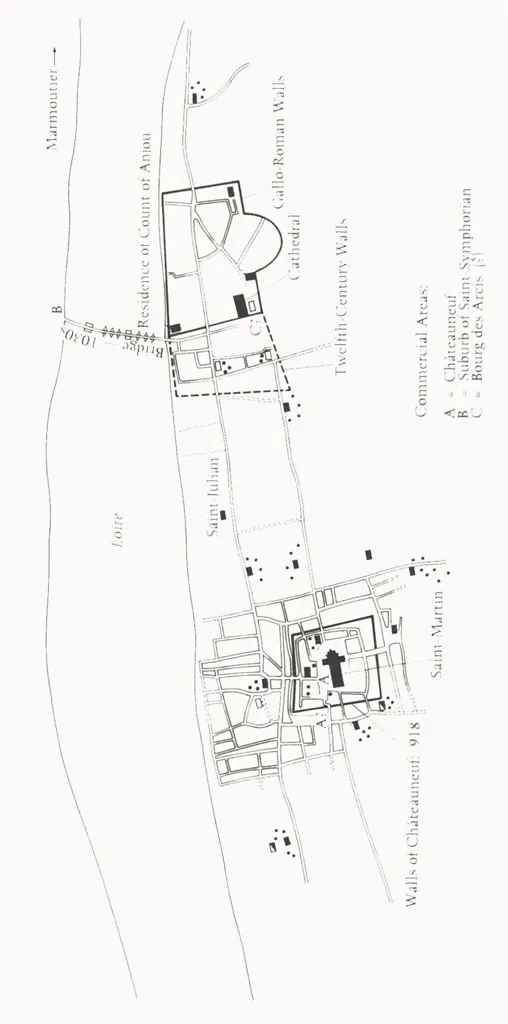

In Tours, the Viking invasions stimulated a further development around Martin’s tomb. After the Vikings attacked the town in 903, the inhabitants of Martin’s suburb decided to enclose their neighborhood with a defensive wall, which they completed in 918. Tours became a double town, and “new castle”—Châteauneuf—fell under the seigneurial jurisdiction of the basilica of Saint-Martin rather than that of the cathedral (see map 3).12 In the tenth and eleventh centuries, while the cathedral town stagnated, Châteauneuf developed into a thriving commercial center whose artisans, money changers, wealthy merchants, innkeepers, and tavern owners provided services for the pilgrims to Martin’s tomb. The eleven parish churches that had already been built in Châteauneuf by the end of the eleventh century indicate that it supported a thriving lay population. The cathedral town, by contrast, had only two parish churches.13

MAP 3. Tours in the twelfth century. Adapted from Galliné and Random. Archives du sol à Tours, 31.

Even the abbey of Marmoutier, which Martin founded as an ascetic refuge soon after he became bishop, bore the marks of Romans, Germanic tribes, and Vikings. Martin’s biographer, Sulpicius Severus, emphasized that the spot—two miles east of Tours on the opposite bank of the Loire—was “so sheltered and remote that it did not lack the solitude of the desert.” But this was an exaggeration, contrived to highlight the similarities between Martin and the monks of Egypt. To be sure, Marmoutier was, as Sulpicius indicated, hemmed between the river and a cliff, and the original monks sought shelter in caves carved out of the soft chalk embankment, just as peasants of the region—the troglodytes—do today. But Martin was not the first to inhabit the site of Marmoutier, and indeed the ruins of first- and second-century Roman buildings may have attracted him to the spot.14

During the eras of both the Germanic and the Viking invasions, the religious life at Marmoutier declined. Ultimately, however, the disruptions of the ninth and tenth centuries may have helped to stimulate both the growth of the European economy and the flowering of monasticism, of which Marmoutier was a principal beneficiary. Reformed and restored at the end of the tenth century, Marmoutier became, in the eleventh, one of the most powerful Benedictine monasteries in western Francia. Indeed, the wealthy monastic complex supported an active community of artisans and lesser merchants, who settled in the parish of Saint-Symphorian, across the river from the cathedral. After the 1030s, when Odo of Blois built a bridge joining the north side of the Loire to the cathedral town, Saint-Symphorian developed into an important suburb of Tours (see map 3). Marmoutier and its suburb lay outside the city itself, but they constituted an essential part of its economic, social, and symbolic fabric.15

Building on Roman founda...