![]()

CHAPTER 1

Using Art to Treat Eating Disorders

Let each man exercise the art he knows.

Aristophanes (c. 448–c. 388 BC)

Why art?

Art can stimulate psychological growth and support healing in several ways. Inherent in the art itself are properties that can promote growth. Art can produce significant personal symbols as well as tap into universal themes. Art heals because of the way people react to the artistic process and to the images produced. Therefore, when using art in therapy, there is knowledge to be gained from observing the person creating the art, by witnessing the process of producing art, and from viewing the art product itself (Ball 2002; Schwartz 1996). All are equally valuable sources of therapeutic information.

Persons with eating disorders are often overly reliant on verbal defense mechanisms such as rationalization, intellectualization, and persuasion. They obsessively discuss and argue with friends and family about food and weight-related topics such as the caloric value of food, fad diets, and body image. Displaying this knowledge helps the eating disordered individual feel a sense of control in relationships (Reindl 2001; Way 1993). The same defense mechanisms, used to protect the self and provide a sense of control in the world, are also used in verbal psychotherapy (Matto 1997). Reliance on rationalization, intellectualization, or arguments can slow progress in therapy and create frustration in both patients and therapists. Eating disordered patients often try to protect themselves from the intimacies of psychotherapy, and relationships in general, by arguing about food, calories, and weight – issues irrelevant to psychological healing. The use of art can help focus therapeutic work on relevant issues. In addition, art provides a different method of communication where language does not interfere (Matto 1997; Rehavia-Hanauer 2003; Schaverien 1995). Art aids the focus on strengths and positive qualities because art often touches on universal healing themes (Levens 1995b; Makin 2002). Art more easily allows the practitioner to see beyond the symptoms and negative self-presentations of eating disordered persons. In addition, the use of art promotes an active role for patients in treatment. Patients are empowered by their active participation in recovery (Farrelly-Hansen 2001).

Because art uses images it bypasses language. Consequently, using art in therapy can cut to the heart of an issue more quickly than verbal psychotherapy. Images can bypass language-based defenses to reveal inner truths (Levens 1995a; Malchiodi 2002). Persons who experience art-facilitated therapy are less likely to verbally censor, argue, or confuse themselves and are more likely to be open to the sometimes surprising image answers pulled by the art from deep within themselves (Levens 1995a, 1995b; Makin 2002; Rabin 2003).

An example of this openness came from a woman suffering from anorexia nervosa who was a reluctant participant in psychotherapy and who was especially resistant to art therapy. This woman talked about how little food she consumed and argued that despite eating so little she really was incredibly fat. She talked on and on about how worthless she was if she weighed more than a certain amount. Her primary therapist, who used verbal psychotherapy, experienced this woman as difficult to work with, controlling, and negativistic.

In her first session using art media, the woman chose a black paper and a yellow chalk pastel. In explaining her image, which is displayed in Figure 1.1, she stated that she purposely chose the color yellow because she disliked it and she was determined to dislike art therapy. However, she made some shapes and found that they were pleasing in several ways: She liked the circular and other organic forms. She liked the way the yellow pastel stood out against the black background paper. Finally, she liked the way that the chalk dust flowed from the image making her think of the Milky Way. The woman admitted that the image was too pleasing so she chose another deeply disliked color, purple, and purposely made heavy jagged lines across it. Again, she was surprised that the resulting image was pleasing to her. She liked the contrast of the purple on yellow and she thought that the combination of jagged lines and circular shapes looked like a piece of music.

Figure 1.1: “Beautiful Symphony” – Art evokes healing responses from negativistic patients

After silent contemplation, the woman said that the art experience and the image she created taught her something about her recovery from anorexia nervosa. She explained that recovery would likely consist of discovering parts of herself that were individually disliked or displeasing but, in the end, the overall effect would be like experiencing herself as a beautiful symphony. The art experience cut through her previous tendency to intellectualize and obsessively discuss her food intake, body image, and weight. The image revealed something beautiful about her regardless of how she would have liked to deny it. This same healing revelation probably would have taken much longer without the help of the art experience. The image and the process of making it pulled an affirming attitude from deep within this previously negativistic woman.

This example also demonstrates that the process of creating art can be just as important as the image produced. If the woman in the previous example had not gone through the process of purposely choosing colors and shapes that were disliked, but whose combinations resulted in pleasing images, she would not have had the same learning experience. In fact, the same lesson would not have been learned in verbal psychotherapy if the woman had tried to explain or rationalize her likes and dislikes. The artistic process played a vital role in teaching her about herself and helping her actively engage in recovery. Therapy with eating disordered patients often involves long periods of silence (Makin 2002). Patients are filled with shame which prohibits them from talking freely, or they are defensively guarding their secrets. The use of art helps fill periods of silence with productive activity. Patients can participate in therapy without having to reveal themselves verbally earlier than is comfortable.

Many people have not used art media since elementary school. Their struggles to master the half-forgotten materials during the creative process can teach or reinforce approaches to problem solving (Matto 1997; Schwartz 1996). This process can include finding something beautiful even when determined not to do so, as it did for the woman described previously. Sometimes mastering the materials means trying again and again. I have witnessed the creative process pull previously undemonstrated determination, perseverance, and resilience from patients as they work with unfamiliar art media and struggle to communicate essential information about themselves through images. Growing competence with the media promotes a sense of mastery and control that is not rooted in eating disordered behavior. It has been my experience that when working with art media the person not the disorder is in charge. The person is no longer a prisoner of the eating disorder when involved in making art. Invariably there is a great deal of learning from the creative process and a great sense of pride in the self and the completed product.

The art product or image produced can convey information directly or indirectly to the creator. Directly communicated information comes in the form of representational images. However, even in what appear to be straightforward representations, variations in the formal artistic elements such as size and placement of figures, colors chosen, and the use of space are used to express additional information. Two persons, given the same directive to draw their families, can convey vastly different feelings with different sizes, colors, and placement of figures. One person might represent her family by drawing four separate small figures with white space surrounding them. The resulting picture would feel isolated and lonely. Another person might represent his family by placing four figures so closely together that there is no real separation between them. The feeling in the second picture would be undifferentiated and oppressive.

The use of art allows one to demonstrate what may be difficult to put into words (Fleming 1989; Lubbers 1991; Wiener and Oxford 2003). What patients find difficult to explain verbally may be more readily articulated with colors, shapes, and lines. Thus, images act as short-cuts to the expression of difficult concepts or emotions. Writing in The Soul’s Palette (2002), the prominent art therapist Cathy Malchiodi called images “midwives” between experience and language. She explained that a simple image can express quickly and easily what would take hours to explain in words. Facilitating expression is especially important in working with people with eating disorders who have often given up their original voice to become what others wanted them to be (Andersen, Cohn, and Holbrook 2000; Reindl 2001; Thompson 1994). Sometimes confronting himself in the art product is a patient’s first experience of his authentic self, or the first exposure to previously denied or split off parts of the self (Levens 1995b; Makin 2002; Rabin 2003).

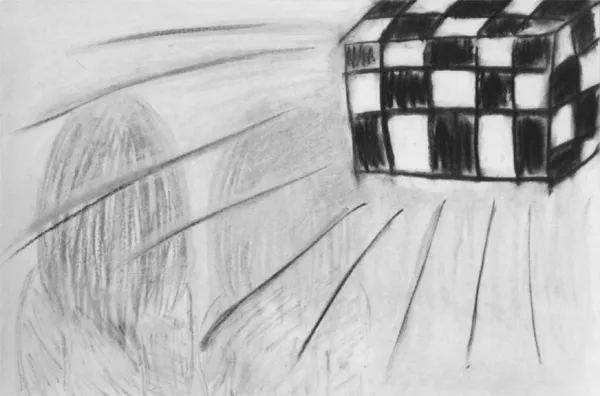

Unlike words, images can easily include multiple feelings and relationships (Malchiodi 2002). Images can contain and explain varied ideas, emotions, and conflicts in ways that words cannot. Art is an effective container for, and liberator from, the ambivalence that persons with eating disorders feel about recovery. The ability to contain and explain two opposing feelings makes art images uniquely communicative. The young woman who made the image in Figure 1.2 used it to help clarify for her parents the ambivalence she felt about recovery. She explained that anorexia nervosa was a safe set of rules and rituals (the checkerboard box in Figure 1.2) that she used to govern her life. She added that while in psychotherapy, she had also realized that the eating disorder was a trap (also the checkerboard box, in Figure 1.2). She explained that she was working toward having relationships replace the eating disorder, but they did not yet feel comfortable. The young woman’s parents were better able to understand their daughter’s ambivalence after seeing this image; they could see her struggle: the safety and the trap of anorexia nervosa. They were less likely to admonish her with statements such as, “there is nothing positive about this deadly disease.” They were better able to support their daughter in relating to others rather than retreating to food rituals. The empathy that the parents developed about their daughter’s dilemma eased a conflict between them and greatly facilitated recovery.

Figure 1.2: “Checkerboard Safety Net/Trap of Anorexia Nervosa” – Art helps demonstrate ambivalence

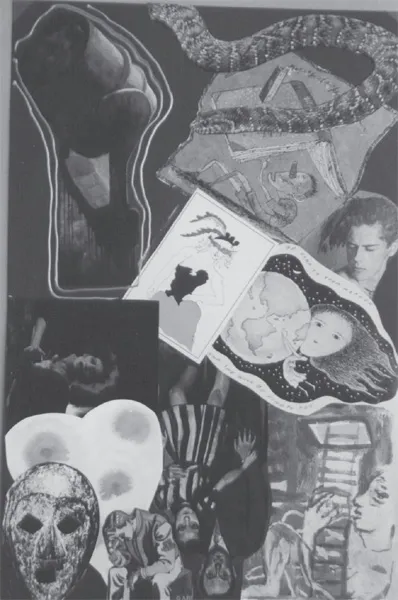

Images can speak to us indirectly using metaphors. The checkerboard safety net/trap is a metaphor in the previous example. This communication process can be described as the unconscious (the part involved in creating) speaking to the conscious (the part involved in perceiving the finished product). The conscious self only had been aware of the safety of the eating disorder until the unconscious self revealed it to be a trap. The art product can have a dreamlike quality as metaphors speak in a similar fashion to dreams (Malchiodi 2002). For example, a person feeling emotionally overwhelmed might picture himself drowning or someone cut off from her emotions might depict herself as a robot. Metaphors can be explored on many levels in order to deepen understanding about struggles and emotions. Figure 1.3 was a bulimic woman’s metaphorical explanation of her purges. The large bucket in the upper left-hand corner of the picture is pouring out the emotions and thoughts being purged in the form of images. The young woman worked quickly to produce the collage and was not aware of everything that her purges contained until she was confronted with the finished art product. She was particularly struck by the heart in the lower left of the picture, which she found in a box full of precut images; it had been created by another person. She exclaimed with wonder that its inclusion in her collage showed her how she was purging “other people’s pain” taken on inappropriately. She explained that until she viewed her collage, she was not aware that her purges had anything to do with her taking on other people’s burdens.

Figure 1.3: Art helps display the complexities of what purging means to a bulimic patient

Figure 1.4: What bulimia nervosa is like – Art helps define the disorder as chaotic and isolating

Another unique aspect of therapeutic art images is that they chronicle the progression of recovery. Sometimes material in verbal psychotherapy is elusive and not easily recalled, especially when highly charged with emotion. An art product is a lasting reminder of therapeutic work (Matto 1997; Rabin 2003; Wiener and Oxford 2003). It can be saved and returned to later for further contemplation. The original image or a color photocopy may also be used later in a different therapeutic manner: reduced, recycled, or reused. Changing images in the art process can represent a first step towards changing behaviors, thoughts, or feelings in life. The young woman whose images are represented in Figures 1.4 and 1.5 demonstrated how the chaos of her early life and subsequent bulimic behaviors prevented her from having fulfilling and nurturing relationships. In a later session, she changed the chaotic image in Figure 1.4 into the joyous birthday party in Figure 1.5 to show what she wanted to attain in her life: celebration and closeness, not chaos. Making the image was a first step towards making the change in her life. She demonstrated to herself what she wanted as well as one concrete way of getting it. The young woman was simply asked if she would like to alter the original image in any way; she was given no further suggestion or direction. The fact that she produced the solution for herself – the therapist did not suggest it – and that it was documented in a way that she could not forget or deny was an empowering first step toward change.

Figure 1.5: “Celebration” – Art helps patients take the first step toward change

In summary, art expression provides information from three sources: the person, the process of creating, and the final product. Art expression can help people come to terms with the effects of eating disorders on their lives and connect with the innate healing wisdom that exists within. The challenges of working with different art media can emphasize forgotten strengths and capabilities. Images can speak directly and metaphorically about long-buried positive qualities. Issues emerge more rapidly when painting, drawing, and sculpting than with words alone. Finally, the image on paper serves as an enduring testament to the work performed in therapy – a witness to the internal wisdom that every person suffering from an eating disorder has within him or herself.

art not Art

When embarking upon a therapeutic journey using art as a healing medium, it is important for patients and therapists to understand that no artistic talent is required to be effective. Art therapist and auth...