![]()

CHAPTER ONE

How the Regenerative Model Evolved

The ‘building bricks’ of the regenerative model

The effects of trauma on the development of young children were not fully understood when society discovered the extent to which children were being sexually abused. As knowledge grew regarding child sexual abuse during the final two decades of the last century, so our understanding of the damage to child development was increased. As a probation officer in 1975, I found myself working with adolescents, so-called ‘delinquents’, both boys and girls, some of whom were also telling me about their early physical and sexual abuse. The links between the abuse (which had seldom been reported or confirmed) and their subsequent behaviour seemed to be obvious, but there was little research on the subject. The connection with physical abuse was strongly denied by abusing parents who, while admitting the abuse, declared that it was justified punishment for bad behaviour. At that time sexual abuse was rarely discussed, was referred to obliquely by children, was denied by parents, and often by society in general. I was also working with paedophiles, but the compulsive nature of their behaviour was not recognized at the time and no treatment was deemed to be very effective.

However, as research into the subject proliferated, so did the publications. Herman (1981) brought a feminist stance to the subject of father–daughter incest, and Sgroi (1982) introduced a medical perspective to work with survivors. Finkelhor (1984) discussed research and theory in a practical way and threw some light on the motivations of abusers, while Alice Miller (1987) discussed psychotherapy, and stressed the psychological damage caused by abuse. By now working for the NSPCC (National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children), I found that there were links between the physically abusive behaviour of some women to their own children, and their own early physical and sexual abuse, and I published a paper on this with my colleague, Alan Prodgers (Bannister and Prodgers 1983). Many of the young mothers with whom we worked had histories of physical and sexual abuse by their own families and others had been severely neglected during their childhoods.

Having contacts with Rape Crisis groups, and working with a support group for women who had been sexually abused, gave me further insight into the extent of the damage, and the ongoing repercussions through the second and third generations. I was also finishing training as a psychodramatist and as a dramatherapist and working with many abused women, mostly in therapeutic groups. I began to incorporate play therapy into my work with abused children, so I was influenced by the work of Moreno (1977), Jennings (1975) and Axline (1969). Moreno’s theory of child development plays a key part in the practice of psychodrama but it was only later that I realized that it was also the key to my understanding of the effects of sexual abuse on young children.

Devising the regenerative model

Some aspects of my model then were already in place when I undertook the task of building a new team with the NSPCC, specifically to increase knowledge of child sexual abuse, and also to work therapeutically with children and families where such abuse had occurred. My own practical work with traumatized young people and with adults who abuse, was echoed in the experience of others who joined the team. A sociological understanding of the reasons why child sexual abuse was prevalent in our society emerged from our discussions and disagreements. We believed that imbalances in power were at the root of child sexual abuse. Some team members were familiar with creative therapies and with theories of child development which I have mentioned above. It took some time, however, before the team began to realize the full extent of the damage caused by early childhood abuse within the family, and to recognize that there were some circumstances where that initial damage could be lessened (by having supportive grandparents for instance).

A creative team is more than the sum of its parts. Our team contained social workers, administrators, a psychodramatist, a dramatherapist, and a play therapist. The team changed but the mix of skills remained fairly constant. Individually we all brought some expertise, some experience, some knowledge of childhood abuse, physical, emotional and sexual. Working constantly with deeply traumatized children meant that the team relied on each other for support. We were also training new members of our team, plus other teams, so we had to keep abreast of the mass of information on sexual trauma which was being discovered constantly. We met regularly as a team and shared our skills, knowledge and experience. We also shared our ideas and our hopes and fears. Our skills, however, were difficult to measure. It was clear that abused children responded to us but it was less clear if, and how, children benefited from our work. Those who cared for the children often stated that ‘difficult’ child behaviours had reduced, that communication between themselves and their children was improved, and that the children looked forward to the therapy sessions. The children themselves were usually eager to attend sessions, although painful and angry feelings were sometimes released. Sometimes their behaviour appeared to regress and carers found it difficult to cope with ten-year-olds who wanted to be cuddled and rocked after they had got in touch with their own vulnerability in a session.

I found myself asking questions which I could not answer:

• What exactly was the therapist doing in a creative therapy session with a sexually abused child?

• How was this affecting the child and how was it changing child behaviour, if at all?

• If there was a lasting effect on the child, why was this happening?

Trying to answer these questions was the purpose of the research which I undertook later. One insight which I did have in the beginning was the realization that in the ‘creative sharing’ of the team we were generating something which was ‘extra’ to the individual skills and experience which we already had. There were similarities in the close bonds which we forged with other team members and the therapeutic bonds which we made with children. During our team sessions we were assessing and changing our own practice just as the children appeared to be assessing and changing their own behaviour in therapy sessions.

We called our work ‘the interactive approach’ because children and therapists were equally valued in the work, and ‘action’, i.e. play, was the key to the therapy. We soon became aware, however, that some children seemed less able to benefit than others. We looked at our own vulnerability within the therapeutic team, and realized that we could not contribute fully to our discussions unless we felt safe from judgemental reactions. So we assumed that children felt the same, in therapy. We also realized that we needed support from people outside the team (family and friends) in order to function fully, away from the work setting, and so we assumed that the children did too.

The Regenerative Model

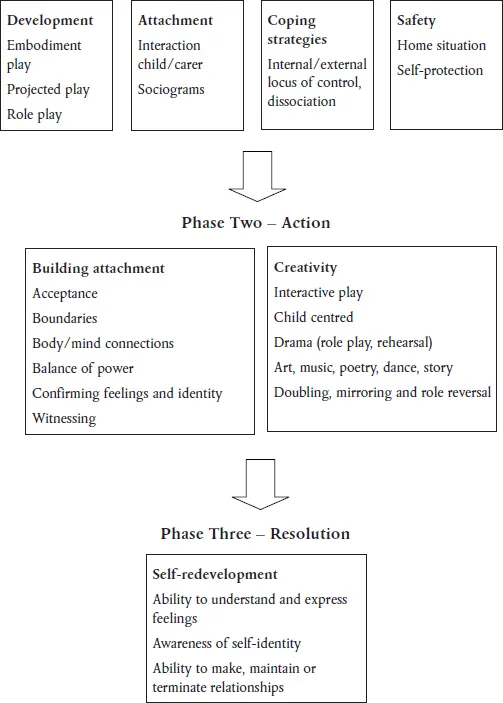

Phase One – Assessment

Figure 1.1 A model for working with children who have been sexually abused

We therefore put in place an assessment procedure which later became the basis of Phase One of the regenerative model (see Figure 1.1). The philosophy behind the model is explained fully in Chapter Eight, but practically, we looked at children’s development using a dramatherapy theory of play (see later in this chapter) and we decided whether their play included embodiment, projected and role play. Children enjoy embodiment play such as sandplay, clay and modelling, messy finger painting, and water play from a very early age, and projected play with dolls, puppets or drawing and painting materials is usually included within their first two years. Role play may begin at any time after that (including ‘dressing up’) and usually by five years children are accomplished in play at all levels and include some of each over a series of sessions. Many of the children that we saw were stuck in embodiment or projected play and it seemed that their development had been impaired or delayed at an early stage. Often the abuse could be traced to early beginnings at this crucial stage of development. We knew from experience that these children took much longer to show some signs of recovery.

Also during the assessment procedure we looked at the attachments which they had to current carers. We also assessed attachments to former carers or parental figures. We were informed by the work of Fahlberg (1994) and Howe (1995) in particular. Children who had no secure attachments were often more difficult to engage in therapy. When an attachment was eventually made with the therapist it was still often an ‘ambivalent attachment’ (Ainsworth et al. 1978) or a ‘disorganised attachment’ (Main and Solomon 1986). Again, these were the children whose recovery took a greater time. We noticed, however, that children who had managed to make some kind of attachment to a current carer (often a foster parent) responded better to the therapy.

The child’s coping strategies were important to assess during therapy, to ensure that these were not eroded too soon and were valued for what they were. We found that children who were abused often accommodated to their abuse by using extreme coping strategies. These were sometimes related to gender but not exclusively so. Many boys, and some girls, had become very controlling in their behaviour in order to cope with feelings of powerlessness. These were the children whose behaviour was often classed as ‘unmanageable’ or ‘difficult’. Others, mainly girls, became stuck in their victim role and became bullied, clingy, or ‘whingeing’, much to their own distress and that of their current carers. It was important not to focus on a programme to reduce these behaviours too early, or the child would feel even more vulnerable. The exception to this is the child who is sexually abusing others. Obviously a behavioural programme should address this, to protect the child and others, but therapeutic work on the child’s own abuse should also be run alongside, if possible.

Similarly, the use of dissociation by the child, which is a very effective coping strategy during periods of extreme stress, violence or pain, was noticed and explored, but not discouraged until the child felt safer. Safety, therefore, was the key to successful therapy, even if that meant things moved at a slower pace. The current home situation was also, therefore, carefully assessed to ensure that the child was not still in danger of abuse and that the child had some skills of self-protection in place. Great care was exercised regarding the latter. If skills of self-protection are taught at too early a stage in the therapy the child may well feel that the ‘reason’ for their abuse was that they had failed to protect themselves and thus their own guilt is compounded.

It will be seen from the above that the attachment process between therapist and child was assumed to be highly important (as it is in most, if not all, therapy). We advocated ‘total acceptance’ of the child, together with firm boundaries put in place by the therapist. Body/mind connections were always kept in mind (as in most kinds of creative therapy), as was the balance of power between child and therapist. Stress was laid on the confirmation of the child’s feelings (some children were very confused and unable to experience feelings) and on confirmation of identity, which also was usually unclear. The importance of the therapist acting as a witness to the child’s statements and actions was stressed.

All therapy was interactive and child centred and usually included drama, art, music, poetry, dance, story, and the psychodramatic techniques of doubling, mirroring and role reversal. Progress was determined when the therapist felt that a child had gained an ability to understand and express feelings and had some awareness of self-identity. When a child also enjoyed the ability to make, maintain and terminate relationships, it was felt that it might be possible to terminate the therapy.

It will also be seen from the above that although the therapy appeared to be largely successful, we had not fully answered our earlier questions of ‘What?’, ‘How?’ and ‘Why?’. This then was the purpose of the research which I undertook later, with the support of the NSPCC. I realized that Moreno’s theory of child development was crucial to my understanding of the damage inflicted by repeated sexual abuse of children in their early, developing years. I also realized the importance of the dramatherapy theory of play development in our practice and treatment. These two theories, together with the whole concept of play and its importance in development, were the key factors in our practice. During the so-called ‘decade of the brain’ (1990s), my subsequent understanding of the neurological effects of abuse in a child’s developing years provided great insight into the reasons why children are so damaged by it. My research enabled me to bring together all these factors to produce the regenerative model for working with abused children.

Moreno’s theory of child development

Moreno suggested that children’s development depends on their environment, and particularly on their parents or carers. His theory of child development was published in 1944 (Moreno and Moreno 1944) and later refined in 1952 (Fox 1987). Jacob Levy Moreno was an Austrian psychiatrist who invented the method of psychotherapy known as psychodrama. He suggested that the development of an infant is accomplished in three stages: the first stage of finding identity, the second stage of recognizing the self and the third stage of recognizing the other. He suggests that these stages are reflected in the actions of the primary carer for the infant.

For a small infant who is still in the identity stage, the primary carer will often ‘double’ the child to assist in the expression of feelings. For instance, mothers may talk to their babies, trying to interpret their cry and trying to put themselves in the child’s place. They may suggest that the infants are cold or hungry and will try to pacify them. The expression of feelings, and some acknowledgement of this by others, helps the child to create an individual identity. Doubling is also a psychodramatic technique where one person stands alongside another (the protagonist) and, copying body language and voice tone, makes explicit feelings which are unspoken by the protagonist. These can be corrected or modified by the protagonist until a clear understanding of the protagonist’s feelings is gained both by the double and by the therapist and other group members (if the work is part of a therapeutic group). This is similar to the process of one or more caregivers trying various interpretations until the baby is pacified.

The technique of doubling is central to psychodrama and it helps protagonists to clarify and express deeper levels of emotions (Blatner 1997). A special application of doubling (the containing double) is used by the psychodramatists Hudgins and Drucker (1998) when working with sexually abused adults, in order to contain the trauma. Moreno suggested that this technique is used instinctively by a competent carer who reacts to the child’s cry or smile with words and actions which seek to interpret that which the infant is trying to express. This enables the child to express itself in a way which is understood, at least by the main carers and also, often, by siblings and others in the immediate environment. This confirmation of the child’s identity begins at birth and continues throughout early childhood.

Once the child’s identity (or personality) begins to form the main carer then automatically seeks to reflect this back to the infant by ‘mirroring’ behaviour. This is the second stage of development. Mirroring is also a psychodramatic technique whereby one person simply repeats the words and actions of another (the protagonist) to show them how their actions are perceived by others. This must be done in an honest way which does not mock or exaggerate. Infants are able to recognize their own reflection in a mirror at an early age and also appear to recognize reflections of their own behaviour when this is repeated by a trusted carer. (The Peek-a-Boo game may illustrate ...