![]()

SECTION TWO

Play Assessment

![]()

CHAPTER 5

Play Assessment:

A Psychometric Overview

Ted Brown and Rachael McDonald

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

This chapter will provide an overview of psychometric measurement issues in the context of the assessment of children’s play. More specifically, the reasons for assessment, stages in the assessment process, types and characteristics of assessment, and contextual influences on play assessment will be discussed. The authors outline measurement properties, reliability and construct validity and demonstrate how effective assessment can facilitate children’s optimal participation in play.

REASONS FOR PLAY ASSESSMENT

Children’s play is often assessed by child therapists, health care professionals and educators (Bruce 1999; Leech 2007; Parham and Fazio 2008). Rogers and Holm (1989) classified the purposes of assessment as: predictive, discriminative, descriptive and evaluative. Predictive assessment provides some indication of expected skill levels in regards to future performance. For example, a child exhibiting poor co-operative play skills in kindergarten might predict that child having later difficulties with team sports participation in primary school. Discriminative assessment involves using norms to measure and compare performances for the purpose of diagnosis, placement or establishing the level of function in comparison to the normative group. For example, a child’s symbolic play skills can be assessed using a standardised test and compared to matched age-level norms to determine if performance is above or below average. Descriptive assessment is simply determining a profile of a child’s play skills and interests while evaluative assessment involves testing methods that are sensitive enough to detect clinical change when used sequentially. An example would be a child’s play skills being evaluated before an intervention programme is started, half way into the programme, and then again at the end of the programme.

There are a number of reasons for conducting play assessment. First, assessment is necessary to establish a baseline of the individual child’s performance skills for service planning and therapy intervention. Assessment can be used to inform decisions regarding specific interventions. For instance, a child therapist working in the American primary school system may evaluate a child’s play in order to establish goals for that child’s Individualised Education Program (IEP). To accomplish this, she might use the Pediatric Interest Profiles (PIP) (Henry 2000, 2008) to establish a baseline of a child’s play and leisure interests and participation that could inform the IEP process. Second, play assessment can be a means of documenting change in the clinical or developmental status of a child. A therapist might use the Test of Playfulness (ToP) (Bundy et al. 2001; Skard and Bundy 2008) to observe a child’s free play in a naturalistic social play environment in order to monitor the child’s progress at different points during a trial of clinical interventions focused on specific play-related abilities. Third, objective play assessment results can be used as a means of supplementing subjective clinical observations. For example, the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA) (Stagnitti 2007) could be used to provide objective and systematic information as well as clinical observations about a child’s pretend play skills. Fourth, play assessment results are sometimes used as a goal post or marker for funding thresholds for publicly or privately funded services (i.e. the eligibility for funding for an educational assistant within the classroom). The Play in Early Childhood Evaluation System (Kelly-Vance and Ryalls 2005), Infant-Preschool Play Assessment Scale (I-PAS) (Flagler 1996a, 1996b) or the Child Behaviors Inventory of Playfulness (CBIP) (Rogers et al. 1998) might be used as part of a battery of assessments to establish eligibility for additional educational resource funding within a kindergarten classroom for a child with special needs.

Fifth, play assessments are completed as a means to assist with client-centred or family-centred programme planning for children and collaborative goal setting or intervention planning with parents and carers. Play assessment can be used as part of the process of engaging parents and carers in early intervention programmes. Appropriate assessment strategies enable professionals to include individuals and their families in the process of selecting the most compatible and effective interventions for them (Law and Baum 2005). Sixth, assessment allows therapists to evaluate children’s level of play engagement since it is important to know how engaged they are in play to determine the best methods to assist them.

Play assessments can also be used as outcome measures in order to demonstrate that a clinical intervention is effective or to facilitate change that leads to improvement. Services usually need to demonstrate to funding agencies that a contracted service has been provided to a client and to show areas where service development might be required or more resources are needed. In this instance, the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale (PPS-R) (Knox 2008) or the Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale (PIPPS) (Fantuzzo and Hampton 2000) could be used to evaluate a play-based early intervention programme designed to promote social and communication skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Similarly, play assessment using the ChIPPA and the ToP could provide specific evidence about the efficacy of therapeutic pretend play and playfulness interventions. Play assessment therefore contributes to the knowledge base of practice and theory of different therapeutic disciplines.

In summary, play assessment may be a management, clinical, client-perspective or professional tool. Therapists have both a professional and ethical responsibility to assess the need for service, design interventions based on assessment information and evaluate the results of play-based interventions. This provides an evidence base for therapeutic play interventions. Different types of play assessment are completed at different stages of the assessment process. These stages and types will now be described.

FUNDAMENTALS OF CLINICAL PLAY ASSESSMENT

Stages of the assessment process

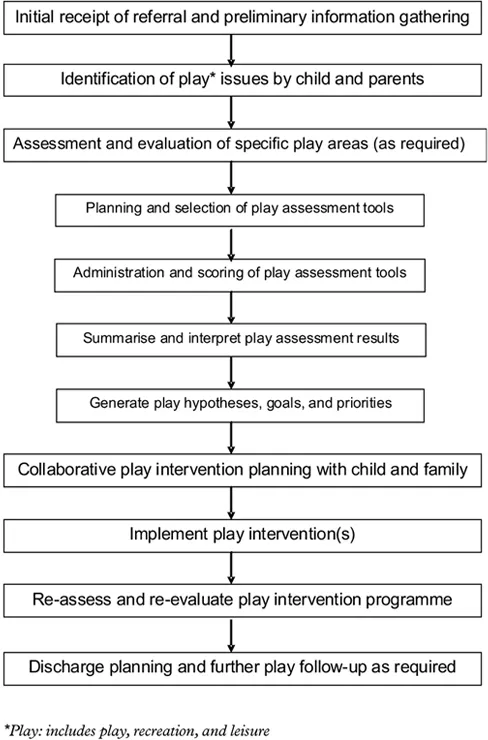

The assessment of play can take place at different stages of the therapy process (i.e. initial referral, during the intervention process, post intervention) and in different settings (i.e. child’s home, school, childcare centre, kindergarten, community health centre, local playgroup, playground or the hospital/clinical setting). The clinical play assessment and intervention process falls into a continuum of steps outlined in Figure 5.1.

Types of play assessment methods and tools

The development of a play assessment involves a process of improvement and evaluation to ensure that the assessment is reliable, valid, consistent, responsive and useful. There are many different types of play assessment tools which child therapists can use in their clinical practice including standardised and non-standardised as well as formal and informal play instruments (Parham and Fazio 2008). Some examples include observational play assessments such as the Assessment of Ludic Behaviors (Ferland 1997) and the Test of Environmental Supportiveness (Bronson and Bundy 2001); play scales completed by parents such as the Children’s Playfulness Scale (Barnett 1990, 1991); and checklists like the Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (Linder 2008), which are used to document the absence or presence of behaviours on a prescribed list. Performance-based assessments usually require a child to complete an activity which is then scored or rated against performance criteria, e.g. Symbolic Play Test (Lowe and Costello 1982).

Figure 5.1 Steps in the play assessment and intervention process

Standardised play assessments have pre-established protocols for administration and scoring of scale items. In the case of children, thei...