![]()

PART IV

Physical Conditions and Other Conditions

![]()

CHAPTER 7

Art Therapy, Health and Homelessness

Julie Jackson

In this chapter I consider how art therapy can provide the opportunity for a client to make sense of, and give meaning to, health difficulties within the context of homelessness. I introduce homelessness and art therapy with this client group. I then use a case study to illustrate how one client used art therapy to explore his sense of self and to think about his future following a double leg amputation.

Introduction to homelessness

I am an art therapist working in the NHS in Scotland with people who have experienced complex trauma and who are homeless, or at risk of homelessness.

To be homeless is to be without a home, but ‘homelessness’ is the ongoing state of not having a permanent home. The term ‘homelessness’ is often used to mean rough-sleeping, however, it also encompasses people living in temporary accommodation, or those at risk of losing their home due to being unable to cope practically or emotionally with their own tenancy.

Campbell (2006) suggests that homelessness physically externalises someone’s internal chaos or ‘outsiderness’. Many homeless clients say that they feel they have ‘never fitted in’, that they have always felt on the periphery of family, peers and society. In her article, Campbell discusses Henri Rey’s description of the ‘claustro-agoraphobic dilemma’. This dilemma, related to attachment, describes wanting closeness and settledness, but finding the emotions they generate intolerable. This may mean that clients with a history of interpersonal difficulties and homelessness may manage to settle in temporary accommodation, but struggle on a psychological level when they move into their own house. Campbell formulates this by saying:

The disruption caused by the move then repeats an original trauma, creating feelings of abandonment in an individual, then the cycle begins again, as the person seeks, and later feels compelled to leave, a home given to them by others (Campbell 2006, p.163)

Bentley (1997) also suggests that interpersonal relationships and self-esteem may be challenging for homeless clients. O’Connor (2003) has written about the centrality of the therapeutic alliance in treating relationship difficulties with this client group. He states, ‘The containment relationship is the first kind of home, before there is an awareness of what we later think of as home’ (O’Connor 2003, p.118).

When people experience homelessness repeatedly, this is sometimes referred to as ‘the revolving door of homelessness’. I have tried to represent this in Figure 7.1 (page 150).

Some people only go around this cycle once before their own resilience, friends/family or services support them to move into their own home. However, others appear to be stuck in the cycle of homelessness, never quite finding a way out into a settled way of life.

Due to the complexity of some clients’ presentations, a holistic model needs to be adopted by services. Someone’s past experience of home, and their thoughts and feelings relating to this, affect their capacity to sustain their own home – so finding a solution to homelessness is more complex than just providing someone with a flat.

In Glasgow it was estimated that 89 per cent of people using homelessness services had experienced repeated traumas (Collins and Phillips 2003). Cloitre, Cohen and Koenen (2006) identify emotional regulation and interpersonal difficulties as being highly prevalent in clients who have experienced complex trauma. Clients often have not had the opportunity to learn helpful coping strategies, due to attachment difficulties or lack of positive modelling. Research (Classen, Palesh and Aggarwal 2005) shows that clients who have had trauma-related issues in childhood also have an increased risk of re-victimisation in adulthood if emotional regulation and relationship difficulties are not addressed.

Figure 7.1 The revolving door of homelessness.

Art therapy and homelessness

Art therapy can provide a less threatening psychological intervention than talking therapy alone. Using art materials can dilute the intensity of the one-to-one relationship that some clients find quite intolerable and which prevents them from engaging with services on an ongoing basis. A ‘slow start’ to therapy with art activity and shared art-making can improve self-esteem, underpin identity work and consolidate the therapeutic alliance. Confidence in the treatment offered can be increased by psycho-education about the impact of both trauma and homelessness. Art therapy within a therapeutic relationship can facilitate communication of the client’s narrative when they lack the capacity to verbalise their experiences. It also enables fragmented parts of memory and ‘sense of self’ to be brought together and viewed as a whole. Images can create an objective distance between the client and their ‘material’; and this can reduce feelings of being ‘merged’ and overwhelmed, as well as creating the opportunity to examine and explore thoughts and feelings.

There is scant research about art therapy with people who have experienced, or are experiencing homelessness, and the majority is based on case studies from the USA (Arrington and Yorgin 2001; Cameron 1996). Davis (1997) describes her work with women in a homeless shelter in New York. She focuses on a 32-year-old woman with a history of childhood trauma, and how she used the materials in art therapy to make house-like structures. There seemed to be a process of the client’s internal sense of self shifting over time. The study shows her artworks as initially fragmented and fragile, then becoming stronger and more solid several months later. This change may have been due to the containment and reliability offered by both the art therapy sessions and the shelter.

Nelson Braun (1997) describes an art therapy open group with men in a homeless shelter. She notes that the use of clay appeared to provide a continuity that other media such as drawing or painting did not. The necessity for the men to return to glaze a piece made the previous week, or to collect a fired piece, appeared to aid a sense of commitment. In this way the art material, and the therapist’s need to ‘see to’ the artwork, offered a continuity that was scarce in other areas of the men’s lives. Nelson Braun suggests that the open studio provided the men with an opportunity to reconsider their self-image, since many of them enjoyed referring to themselves as ‘artists’. This enabled some of the men to see themselves and their strengths and resources in a different light, allowing an expression of potential. Although the literature does not focus on individual case studies, the therapeutic alliance in art therapy appears central.

Health-related difficulties and homelessness

Homelessness can impact upon both physical and mental health. Recent research (Homeless Link 2010) found that eight out of ten homeless clients had one or more physical health difficulties; seven out of ten clients had one or more mental health difficulties; in the previous six months, four in ten had been to Accident and Emergency at least once, and three in ten had been admitted to hospital.

Thomas’ (2011) research entitled ‘Homelessness: A silent killer’ states the average age of death as 48 for a homeless man and 43 for a homeless woman, compared to 74 and 80 for the general population; drug and alcohol abuse are common causes of death amongst this population, accounting for just over a third of all deaths; people who are homeless are over nine times more likely to commit suicide than the general population. Thomas concludes that the health of people experiencing homelessness is among the poorest in our society.

Case study: Jim

Jim was 45 and had slept rough and lived in homeless hostels since his early twenties. He was single, had been unemployed for 20 years and had been using alcohol for most of this period. His long history of rough-sleeping, often in extreme weather conditions, led to developing frostbite, and Jim had to undergo a double lower-limb amputation. He was in hospital for several months after his amputations, followed by a move into a flat; this broke down very quickly. He chose to sleep rough for a while in his wheelchair rather than move into supported accommodation. He then moved into another flat, but found it difficult to settle there. Jim had a huge number of services involved in his care: occupational therapy, physiotherapy, nursing, personal care team, psychiatry, community addiction team and social work. His occupational therapist referred him to art therapy, as she was aware that he had enjoyed attending an art class in the past, and she doubted that he would engage with other psychological interventions. The referral stated that Jim had difficulties in relationships and that his mood and self-esteem were low. As an independent man, he was struggling to come to terms with his freedom being curtailed by the major life change imposed on him by the amputations. In addition, he had begun drinking again after a lengthy period of abstinence and had been diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis.

Assessment

I met Jim in a health centre close to where he lived. He stated very clearly that he ‘wasn’t sure about this art therapy thing’, and that he was not going to tell me anything about himself, as he did not think he needed any help at all. He made little eye contact and his self-care and personal hygiene were poor. He was reluctant to talk spontaneously, to answer my first few questions or to disclose anything personal. In previous notes, Jim had been described as being ‘difficult to assess’ and ‘uncooperative’, so I was aware that I had to build a therapeutic alliance slowly and carefully. I informed him about the team and its role, and about art therapy offering a different way of working that was not based solely on words, but on both of our experiences of the artworks he might make. I spoke of how we could work collaboratively to discover if art therapy could be helpful to him. I suggested that we met for three assessment sessions and then review whether we felt we could find a way of working collaboratively. Jim agreed to ‘give it a go’, albeit rather reluctantly. At this first meeting, I introduced him to the art materials, explaining that through them he could express anything he wanted to and that we would look at it together, and think about how it related to him and his current difficulties. I also set boundaries, pointing out that I would not be able to meet with Jim if he was heavily under the influence of alcohol or if he was aggressive in sessions. Jim, somewhat seriously, agreed to this.

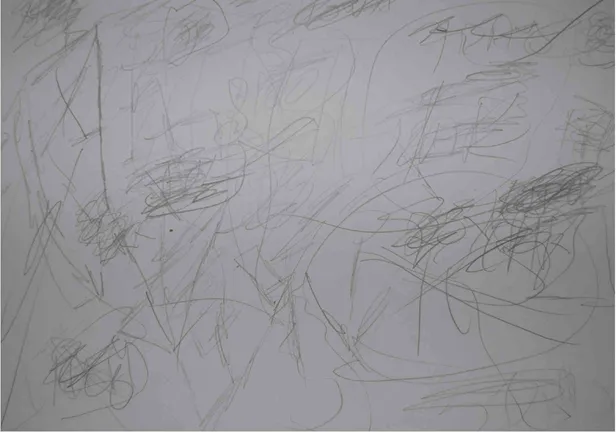

Over the next three sessions, Jim used coloured pencils (black and grey) to write a single word. We quickly established a way of working together where I then read the word aloud, mirroring it back to him, and he took this as an invitation to expand on what the word meant to him (see Figure 7.2, page 154).

Figure 7.2 Jim’s tentative explorations.

For example:

Jim wrote ‘sister’.

Me: Sister?

Jim: I’ve been feeling fed up that I haven’t spoken to her for ages.

Me: Tell me a bit more about your relationship with your sister.

Jim went on to tell me a little about his sister, often drawing and doodling while speaking. He kept his focus on the paper rather than looking at me, and in this manner we were able to piece together a family history. Jim told me about his siblings. His parents had separated when he was young and his mother had remarried, and Jim had enjoyed a close relationship with his stepfather. From an early age alcohol seemed to feature frequently in the family’s socialising. Jim stated that his stepfather had introduced him to drinking shandy when he was seven years old. He described being ‘rewarded with alcohol’ in his early teens when going to buy drink for his stepfather and friends. It was clear that he had enjoyed the group aspect of this ‘drinking culture’, which seemed to be linked to family, friends and belonging. Unfortunately, Jim told me with...