I have spent most of my working life as a mining industry consultant. In this book, I put forward my views on the efficient organisation of the world mining industry. I do this as an industry insider and based on my personal practical experience. The views I express are therefore likely to differ from those of academic industrial economists who will view the mining industry from a theoretical or policy perspective.

Despite this qualification, my account is informed both by my undergraduate degree in economics and by subsequent reading in business administration. Over the past half century, business administration has succeeded in establishing itself as a recognised academic subject at the world’s major universities. It offers a range of techniques and methodologies that are equally applicable to every sector of the economy, ranging from the local convenience store to the world’s largest corporation. This body of knowledge has been commercialised by leading management consulting firms who stress that one of their key advantages is their ability to capture business insights obtained in one sector and transfer them to other sectors. To such companies, the development of industry expertise and know-how is something that may be obtained from the client, or acquired by hiring experts with specialist knowledge, or contracted out to third parties as a last resort.

I take a different view. Sound general management, accounting and reporting principles are as important in the mining industry as in other sectors but they will be insufficient. The mining industry presents a number of challenges that require a different approach for the following reasons:

Thus, the development of industry knowledge and an understanding of its culture become the key requirements of the successful manager rather than a detail to be out-sourced. Industry knowledge includes not simply the obvious – understanding how a commodity is produced, where and why it is used, who the major companies in the industry are, and so on – but also what might be called the ‘deep history’ of the industry so that the mistakes of the past are not repeated unnecessarily.

It is much more difficult to acquire this deep history, in my experience, than simply to acquire generic management consulting skills. An effective mining industry executive needs to become what I choose to call a ‘Renaissance Man’ and acquire skills from, or at least develop a high comfort level with, many disciplines ranging from the obvious technical ones such as geology, metallurgy and engineering, to economics, finance, sociology, anthropology, politics and communications. For most people this requires many years, if not a lifetime, of experience. By contrast, the latest techniques in business administration can be acquired quite quickly through the many excellent Executive Management programmes offered by the world’s business schools.

I have been engaged in providing mining consultancy services for most of my working life, and in recent years with a leading mining consultancy company, CRU International. CRU and similar companies are firmly committed to the development and retention of industry expertise, which, defined in the broadest possible cultural, technical and business terms, is the core requirement for successful management in the industry. CRU’s mission is to help mining industry stakeholders make higher quality and more robust business decisions by deeply understanding and managing the risks involved. Industry expertise is our core asset.

Mining in Perspective

My goal in writing this book is to summarise some of the industry know-how and related analytical techniques that, with the help of colleagues at CRU and other companies, I have managed to acquire and use in 40 years of consulting. I have chosen to do this by providing examples taken largely from a small subset of the 200-odd minerals used by the twenty-first century global economy – coal, iron and steel, aluminium, copper and the fertiliser minerals. These are high-volume mined commodities with the largest environmental, social and political consequences for society. The affairs of the companies that mine them are reasonably transparent. A huge volume of academic studies, technical conference proceedings and business reports about these commodities is also available. Readers who are interested in digging deeper into information that I am necessarily presenting in a highly summarised form can, therefore, readily do so.

Any sampling bias found in this book has to be seen in context. When I became Research Director of CRU International in 1973, my first task was to advise management on the potential diversification of the company’s interests. At that time CRU’s business was primarily related to market research and price forecasting in the copper industry. However, the company was fielding inquiries about many other commodities and was looking to expand the scope of its business significantly. Unencumbered by any prior knowledge of metals and minerals, I therefore began my analysis with a clean sheet.

My approach at that time was simple and I will follow the same approach in writing this book. I listed as many minerals as I could identify and looked up world mine production and the prevailing market price in order to calculate the global revenues associated with the production of each commodity. This analysis revealed that 75% of the value of the world’s non-fuel mineral production was accounted for by just four commodities – gold, iron, copper and aluminium. As an economist, I understood that gold was a currency rather than an industrial commodity. As a transportation expert, I could see that the importance of logistics cost in the overall price made nonsense of the London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouse delivery business model for iron ore. Consequently, my recommendation was that CRU should diversify into aluminium, which appeared to me to be similar to, and a partial substitute for, copper. I am happy to report that this advice was accepted and that aluminium forecasting and consulting quickly became a core business for the company. (A few years later, the LME also diversified into aluminium, which has become its most valuable contract.)

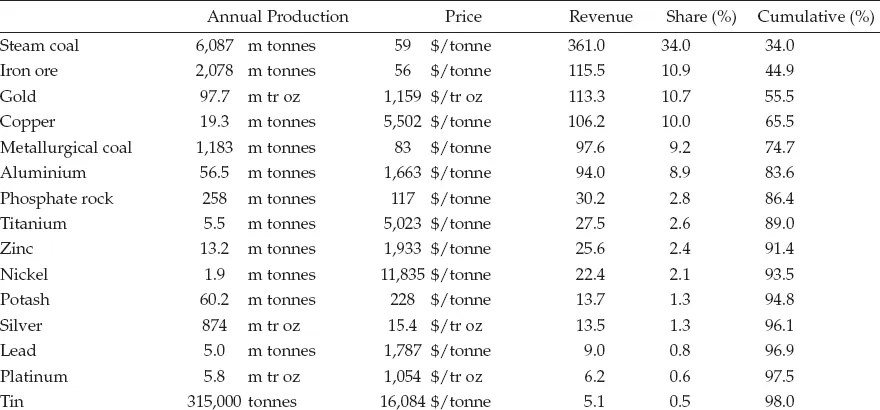

Table 1.1 shows the results of a similar exercise 40 years later. To provide a complete perspective of mining, I have added coal, which is the world’s largest mined product by volume, and I have separately identified steam coal (mainly used in power stations) and metallurgical coal and coke (used mainly to produce steel). Table 1.1 includes all metals and minerals where annual production exceeds $1bn, but excludes gemstones. It shows that in 2015 54% of all mining efforts1 are related to providing electricity and steel, two absolutely essential building blocks of urban industrial society. Without them, it is inconceivable that the planet could support its 7 billion inhabitants.

Steam coal represents approximately one-third of the value of global mine production. Coal is still by far the dominant fuel for the generation of electricity, and its market share has increased. However, it is also the single largest contributor to carbon emissions. Alternative ways of generating electricity reduce these emissions by half in the case of natural gas and almost entirely in the case of renewable sources of power, both of which are growing strongly. However, despite the most optimistic projections for alternative fuels, the world will need coal in today’s quantities (or more) for at least the next 30 years just to keep the lights on, particularly in high population, low income economies such as China and India where power consumption per capita is far below western levels.

A further quarter of the global value of mine production relates to iron ore and metallurgical coal, which are the essential raw materials in the production of steel, the most commonly used material in the modern industrial economy. Indeed, global consumption of steel is approximately 30 times larger than the consumption of aluminium, the second most widely used metal. Steel is widely used in the construction of residential, institutional and industrial buildings of every kind, bridges and highways, railroads and mass transit systems, water and sewerage plants, power transmission towers, and almost all other forms of infrastructure. Another major use of steel is in the production of machinery and other capital goods that are required for the operation of manufacturing industry. Without steel, there is no urban industrial economy.

Table 1.1: Value of Global Mine Production, $bn, 2015.

Source: Author’s calculations from CRU data.

A further quarter of the value of production reflects the production of gold, aluminium and copper. Eight other commodities – phosphate rock, titanium, zinc, nickel, potash, silver, lead and platinum – take the cumulative share to 97.5% of total value. For all practical purposes, everything else extracted from the earth’s crust can be considered as a niche business. Individually, none of them account for more than 0.5% of world mine production.

Minerals produced and used in small quantities can, of course, be crucial to some manufacturing processes, but at the same time the volume and value of world production may be insignificant compared to the major minerals from which I draw my examples in the body of this book. As an example, it may be helpful to reflect upon the concern expressed in recent years over the potential dominance of China in the supply of rare earth oxides (REOs). In 2014, China is estimated to have produced 95,000 tonnes per year of REOs out of a world total of 111,000 tonnes. These minerals (there are 17 of them) are critically important in automotive pollution control catalysts, permanent magnets and rechargeable batteries. Demand is expected to grow strongly as future global demand for conventional and hybrid automobiles, computers, electronics and portable equipment increases. Expanded rare earths usage is also expected in fibre optics and a wide range of medical equipment applications. In other words, REOs play a crucial role in modern, high-technology growth sectors of the economy.

However, the value of global production of all 17 REOs was just $1.65 bn in total, using 2012 prices. Thus, all REOs collectively represent only 0.1% of the value of world mine production. It is worth adding that REOs are not all that ‘rare’ either. According to the US Geological Service, world reserves are 1,000 times greater than current production, and only half of them are in China. In other words, a hypothetical Chinese attempt to squeeze international consumers by restricting exports would have only a short-term impact. The resulting price increases would be very likely to stimulate additional supply from other countries, and the absolute size of the investments required for this transformation would be modest when judged in terms of the industry’s global financial capacity. To put this in perspective, a single new iron ore mine, the Roy Hill project in Western Australia, which came into production in 2016, is expected to have an ultimate capital cost of $14 bn and will have an output worth over $6 bn per year at current prices.

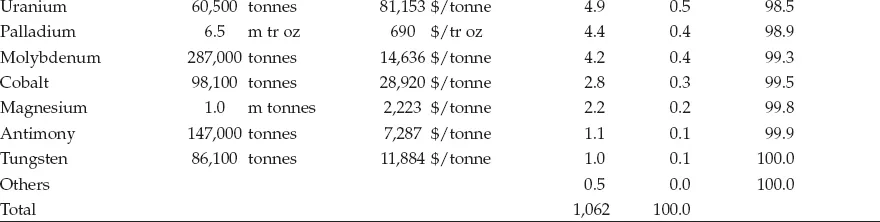

Table 1.2: Value of Production of Extractive Industries, $bn, 2015.

Source: Authors’ calculation using data from Table 1.1 and BP: Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2016 (oil and natural gas production); IMF: International Financial Statistics (oil and natural gas prices).

Another perspective can be obtained by comparing the value of non-fuel mineral production with the value of the production of various fuels. From an overall economic perspective, the energy industry is far more important than the mining industr...