Chapter 1

Roman London and Its End

First to Fifth Centuries AD

One of the star exhibits in the British Museum’s Roman Britain gallery is a bust of the Emperor Hadrian (117–38) (Figure 1.1). Cast in bronze and somewhat larger than life-size, it would once have topped an imposing full-body statue. Its serene countenance has gazed down on visitors to the museum since 1848. This particular bust of Hadrian holds special significance for Londoners, as it was found in the city, dredged up from the Thames in 1834. It evokes one of the most glorious points in the city’s history when, in the year 122, Britain hosted a visit from Hadrian himself – the first reigning emperor since Claudius (41–54) to travel to the province. Where Hadrian actually went in Britain is not known for sure, but there is a very good chance that he at least passed through London, the greatest city of Britain and the principal conduit between it and the rest of the empire. He would have seen a city which, while still retaining a frisson of the ‘wild north’ in the eyes of a well-travelled Mediterranean emperor, represented many of the great strengths of the Roman Empire at its height: grand public buildings; vigorous exertion of imperial authority; and a diverse, prosperous populace.

Figure 1.1. Bust of Hadrian (117–38), British Museum.

London had arrived at this point after less than a century of Roman rule. Another century after Hadrian’s visit to Britain, its position would be rather less rosy, and go downhill during the fourth century. In the course of the fifth century, the city became a ghost town. Nevertheless, two of the cornerstones of medieval London’s foundations had been laid. One of these was its physical form: its location and its walls exercised a powerful influence on the city’s development in subsequent centuries. Indeed, the bounds of the City of London proper still roughly follow the lines of the Roman wall, which was its effective edge for more than a millennium after the walls were built. The other cornerstone was London’s status. It held a symbolic eminence unique among Britain’s cities in the early Middle Ages, and this magnetic quality was founded in part on awareness of its ancient past. As a bishop who travelled to London for consecration in the 830s proclaimed, it was ‘that famous place built by the skill of the ancient Romans ’.1

The survey of Roman London presented here is brief and selective. Many more expansive accounts have been written, which should be consulted for a broader and deeper picture.2 What follows is above all intended as a sketch of the precursor of Anglo-Saxon London, the better to draw contrasts with developments from the fifth century onwards. It also establishes the approach that must be taken to London’s history throughout the first millennium, which depends heavily on archaeological remains. Although the physical footprint of Roman London is known from a large number of small digs, collectively these myriad pinpricks have helped form one of the most thorough archaeological profiles of any city in the former Roman Empire. These excavated remains and artefacts – alas, there are hardly any standing monuments from this period – must be combined with the testimony of chronicles, letters, laws and the like. Diversity is the name of the game in the city’s early history, and the historian must become a sort of magpie, picking from many sources and disciplines: no one form of evidence can tell the entire story.

Origins

The site of London – or, rather, the river that winds through its midst – had been important long before the Romans ever set foot in Britain. Rich offerings were deposited in the Thames, and dredged up in the course of building work in the nineteenth century. The beautiful Battersea Shield (also in the British Museum), for instance, was found during the construction of Chelsea Bridge in 1857. The sacred river is also thought to have lent a name to London: from its earliest appearance in the 60s or 70s, when its name appears for the first time on a recently discovered writing tablet, the settlement was known as Londinium or similar,3 which probably derives from an early Celtic word *Plowonidā, a word composed of two elements related to ships, swimming and water – so perhaps meaning ‘place at Boat River’ or ‘overflowing river’.4 It is assumed that, by the time the Romans appeared in AD 43, this had evolved into something like *Lōndonjon, ‘place at the overflowing river’. No large-scale permanent settlement developed at the place of the overflowing river, however: the concentrations of wealth and power in the south-east of Iron-Age Britain were situated elsewhere.5

Within just a few years of the Roman invasion of Britain, a new town had sprung into being on the northern bank of the Thames. It grew rapidly. A drain found at 1 Poultry, beneath the main east–west road of the fledgling city, was made from timbers felled in AD 47/8, probably as part of the initial land clearance and construction phase.6 In its earliest years, London served as a civilian mercantile centre, supported and overseen by the Roman state authorities but probably driven by trading interests from outside Britain.7 These incomers capitalised on the city’s favourable geographical position, which served multiple surrounding kingdoms and their capitals via the developing road system, and allowed easy and rapid transit by both river and sea. The Roman writer Tacitus described London as ‘undistinguished by the status of colonia [i.e. an outpost of Roman citizens], but widely known for its wealth of merchants and travellers’,8 suggesting that in its earliest days London drew its vigour from trade and easy, frequent connections with mainland Europe. Its rapid growth as part of the new regime in southern Britain made London (along with Camulodunum/Colchester and Verulamium/St Albans) a target of the famous revolt led by the Icenian queen Boudicca in 60 or 61. Although Roman forces did reach the city before it was set upon by the Britons, the governor judged his men to be too few to resist effectively, and so chose to make a tactical retreat and sacrifice London in order to save the province.9 Those who were left had to take their chances, and the archaeological record suggests that their prospects were not good: at least 56 excavations across London have produced signs of burning thought to be associated with Boudicca’s sack of London.10 The city that her army destroyed was already something of a boom town. Almost 120 sites have now produced archaeological evidence of activity from the earliest stages of Roman London, before the burnt layers associated with the events of 60/1.11 It had an open area that may have served as a forum, and a timber bridge across the Thames; the main focus of habitation was east of the Walbrook on Cornhill, with subsidiary areas of build-up situated on Ludgate Hill and across the river in what is now Southwark. As the inhabitants of the city must have lamented when Boudicca’s army marched into view, there were no walls or other major defences around the city at this time.12

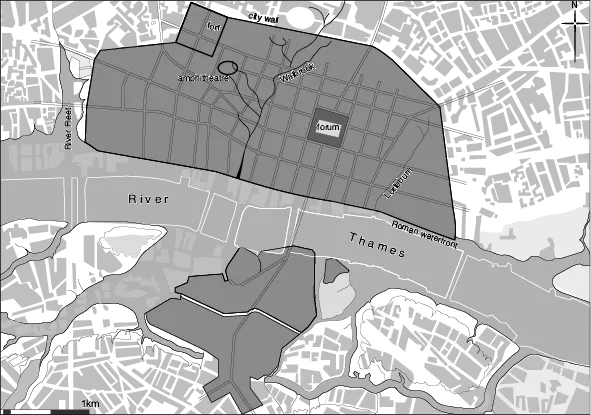

Reconstruction after the Boudiccan revolt was swift: a writing tablet from the city reveals provisions being brought to London under apparently normal conditions in October 62,13 and a fort was erected to protect the recovering settlement.14 Soon it started to gain a wider range of monumental architecture, and to come alive as a community with one foot in Britain and another in the provinces of the empire that tessellated Western Europe.15 The century or so that followed saw Roman London reach its zenith in extent and population. In the words of the archaeologist Gustav Milne, ‘this was not gradual growth but a sudden explosion’.16 The city’s population probably peaked at about 25–30,000, spread out over some 130 ha (Map 1).17

Map 1. Roman London, including principal streets and selected major features of the city.

Living in Roman London

London at this time – and probably for most of the Roman period – was the largest city in Britain, a showcase for the imperial establishment. Although London’s complement of monumental buildings and tombstones was fairly modest compared to that of cities in other provinces, it had a high concentration of them by British standards. Probably most impressive of all was the basilica: a place to conduct business and legal procedures, and a base for various city functions. It was a building of central importance in Roman cities. London’s basilica (best known from a portion that has been excavated beneath what is now Leadenhall Court) grew to be exceptionally large: the biggest recorded one north of the Alps. Situated adjacent to the forum – an open space dedicated to public gatherings and business – the basilica ...