![]()

1

THE SACRED AND THE EARTH

All mystics speak the same language for they come from the same country.

—SAINT-MARTIN

During the 1950s, the time in which I was raised, the extended family was still alive. Most Americans were farmers, and many people lived close to the land on this North American continent, a continent known to many of its native peoples as Turtle Island.

I was raised in Louisville, Kentucky, still a rather small town at that time. I knew four of my great-grandparents and with two of those I was especially close. These two people, Cecil and Mary Harrod, had been born and raised in the latter part of the nineteenth century. They were filled with a spirit and approach to life that is now, in our time, extremely uncommon.

My great-grandfather trained as a physician before the allopaths achieved a monopoly in medicine, before the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics when, among other things, doctors still used herbs in their practice. He was a horse-and-buggy physician in a small town, and he delivered babies at home. He knew the people and they knew him; his office was in his home. He helped babies into the world and he was there when they left it; he’d been present during much of the life that was sandwiched in between.

By the time I was born he and my great-grandmother lived in Columbus, Indiana. They were mostly retired, though there was still an office in back of the house. They also owned a small farm outside Columbus where the family would gather most summers. To travel to that farm meant entering another world from the one in which I lived most of my life. The farm house was a converted hand-hewn log barn that had been built about a hundred years before. It had been disassembled, moved to the farm, and rebuilt. There were two good-sized ponds, the smaller one in the deep woods.

My great-grandparents came from a different time. That time, connected to the roots of what I think of as the heart of what America could have been, soaked into my bones from the day I was born. It was a time of horses and of making what you have. A time of slow pace and rural life, of being close to the land and being a simple people not hung about with high-tech designer equipment. A time of the grain of wood sloping down the line of a hundred-year-old hand-hewn log. A time of the deep veins on the back of a man’s hand. A time of walking in the deep woods and hearing its call—the taste of freshly picked blackberries, the sucking sound a cane pole makes when pulled out of the mud in sudden response to the hungry pull of a fish. A time of finding secret hiding places, and heeding the call of a woman’s voice urging haste so the meal will still be hot. The taste of too-sweet iced tea in big, sweating glass jugs. Laughter around the table and tales of times past when these grown elders were but children themselves. And most of all there was the feeling of being loved deep into the soul and not caring a hoot about the shape of a person’s body or the irregularities of their personality.

My great-grandparents’ way of life soaked into my soul and every fiber of my being. My bones fed on it as did my mannerisms, language, hopes, and dreams. But even more central and enduring was the deep connection with the land that they had shown me. That connection reached into my spirit and told me in its own special language that there was a deeper world, far older, than the human one in which I lived.

But that sense of connection with the Earth was quiet throughout the ensuing years as family died, places were sold, and television replaced the sounds of my elders’ voices. As the space of years increased the greater my feelings of alienation became—from myself, from any kind of enduring values, from the Earth. But those early times, the connection to that land, were like seeds in my soul and eventually, without warning, they burst into growth and changed the course of my life.

They were part of the impetus toward my deep experiences of the sacred when I was seventeen, part of that which led to my trying to understand analytically what had happened to me, part of the map I then created. And eventually, as I began this journey into the world of sacred plant medicine, their threads urged me on to a deeper understanding of my relationship with the Earth.

There is a dimension of human experience, a way of experiencing the world, where plants can talk to human beings and humans can talk to plants. It is a dimension that has been utilized by human beings for most of our history on this planet. Yet in these days and times, that way of life has been relegated to a back alley in a poor neighborhood of the city of man. Those who live there are generally thought of as ignorant and uneducated, superstitious and primitive.

The knowledge that human beings found in exploring that dimension of life, in talking to the plants and hearing the plants talk to them, predates the spread of what today we call science. In that dimension of human experience people commonly sought close contact with the sacred, to know the desire of Creator, and to bring into the world the spiritual visions given them by Creator. Knowledge gained in this manner worked well (as scientific study has shown) and looking over at it from this world of science in which we now live, many are amazed that any of the knowledge found in that other world worked at all. We no longer understand that kind of information gathering; in the industrialized nations we have given it up. In many ways we are the poorer for it. Still, in the backwaters of the world people live as they have for thousands of years, in relation with all life and all living things. As Mother Theresa said, softly, when receiving her Nobel Prize, “It is not we who are poor but you.”

The poverty Mother Theresa spoke of can be felt strongly when comparing the following stories:

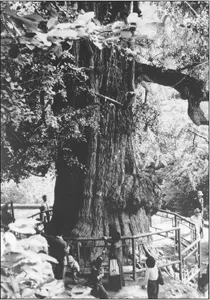

In Korea it is said that in the year 850 A.D. the ginkgo tree was in danger of becoming extinct. It is a tree whose existence is interwoven with that of human beings in Asia, only recently (around 1800) having been introduced into the West. The ginkgo is used for food and medicine and additionally is held to have many spiritual attributes. In that time of danger, many Buddhist monasteries in Korea began taking in saplings to protect the tree from extinction. The Buddhists are credited with saving the ginkgo by taking it into their temple gardens.1 One of the largest ginkgo trees in Asia grows on the grounds of Yongmun-san temple in Korea. It stands 180 feet tall, 15 feet in diameter, and is said to have been planted in the ninth century. This tree, planted to protect the species from extinction, was kept with reverence and prayer for over a millennium. People still make pilgrimage to visit it.

Ginkgo tree in the temple

Some 1100 years later (around the 1950s), a graduate student was finishing his Ph.D. on the bristlecone pine. He had completed his course work and was working on his dissertation, conducting field research in a bristlecone pine forest. He was trying to establish the bristlecone as one of the oldest trees on the North American continent.

He hiked for many days, packing in his equipment, and set up camp. Eventually he located the tree he would study, the tree that he believed was the oldest tree in the forest. In fact, he intended to use a core drill to extract a sample from the tree in order to count its rings and establish its age. He kept extensive field notes and made careful preparations. His Ph.D. degree depended on the research he was conducting on this tree. However, when he was ready to drill a core from the tree, the core drill was not working. He struggled with it for several days trying to fix it but to no avail. He did not have another core drill but he did have a saw. And he cut down the tree and found it was some 4000 years old by counting its rings. A tree already 2000 years old when Christ lived, cut down for a Ph.D.2

It is never possible to share this story without experiencing deep feelings of sorrow. The story brings home the rift between humans and the world, the poverty and illness with which we struggle as a species. The feelings it brings to the heart are often too deep for words. Yet, they are ones all of us try, often with great success, to repress. There is not a one of us who does not know there is something amiss in our world. There is not a one of us who does not carry the grief concomitant with the damage to our home. As Aldo Leopold notes:

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage infliicted on the land is invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.3

A solution to the poverty and illness in our world lies within the ancient capacity for individuals to travel in sacred territory, to reconnect with the sacredness of the Earth, and to develop their own capacity, a birthright of being human, to evoke the holy and once again sit in the council of all life.

The Sacred

Our capacity to recognize and seek out the sacred is one of the basic drives that make up the fabric of a human being, thus shaping our common human ancestry. The sacred as I use it is more akin to the dictionary definition of holy, “having divine nature or origin.” It must be recognized that because the sacred is made up of both nonrational and nonlinear elements, any reduction to simple definitions always fails to capture its essence. One must enter the realm of the sacred and experience its transcendent nature to fully understand it. There is a distinct reality that underlies all religious articulations. It is this reality that, when experienced, is felt to be the REAL, a deeper and more meaningful reality than that we experience in our normal day-to-day lives.

The maps that travelers create from their travels in sacred domains, and the bureaucracy that springs up around control over the map, make up the form and substance of religious movements. The maps correspond to specific lineages of religious or spiritual devotion. All humans have a propensity for how they experience the sacred. For example, human beings may experience the sacred as a territory (Native Americans), as a personification (Christians), or a state of mind (Buddhists). This propensity for how one experiences the sacred can lead to arguments (and sometimes wars) over the correct way to experience the sacred, over “The Way.” But as the eminent religious historian, Mircea Eliade, has said, “There are no definitional limits to what forms the sacred can take.”4 The manifestation of the sacred—hierophany—may occur in any person, place, or thing. The sacred, by definition, can take any form.

Each religious articulation has its place within the human frame. To claim superiority for a religious expression is to claim the thumb superior to the fingers, the foot superior to the leg. Each has its necessary place and function. One must search for the real center of religion and go beyond the linguistic representations contained in religious maps. If one does not, one finds the human, not the sacred.

The sacred has a dynamic aspect in that it has a tendency to manifest itself of its own accord. It tends to come into the world and make itself known. Further, each incarnate form, each object of matter, has a tendency to realize its archetypal, universal, sacred meaning. These two tendencies—that of the sacred to manifest itself and that of each incarnate form to realize its deeper archetype—come together in such a way that any object at any time can incorporate within itself all the power of the holy. When the sacred manifests itself in the world, something in the human allows it to be immediately recognized. A part of the human, most often a subconscious part, experiences the sacred and says to the conscious mind, “that is the REAL.” The conscious mind is then made aware of that which is beyond it and that from which it comes, the sacred.

The intrusion of the sacred into human experience represents a direct transmission of the REAL, a transmission of God, Creator, Allah, Great Spirit. The human who experiences this is made aware of a reality that transcends the human and thus predates human linguistic and cultural constructs. This presents difficulties. How does one retain the memory and experience of something that predates all things human? To explain the experience and to retain memory of it, human beings automatically structure the direct experience of the sacred into internalized symbolic constructs. Thus the sacred comes to be expressed in visions, wondrous feelings, thoughts, and sometimes smells and tastes. This is due to the nature of memory patterning.

Human memory patterns are constructed from aspects of the five senses; that is, memories are encoded bits of sights, sounds, smells, tastes, feelings. Thus the experience of the sacred is translated into visions, sounds, smells, tastes, and feelings even though the sacred is both all and none of these things. Examinations of the written and oral records of those who encountered the sacred show that their experiences were very rich and generally included all of the five senses.5

Strong visionary experience is often accompanied by imperatives for human conduct. Conveyed during contact with the sacred, these imperatives often require the person to whom they are given to act in a certain manner, engage in a specific life work, or make changes in lifestyle or behavior. Because these imperatives are usually interpreted as language when experienced, they most often take on the pattern of language that is already encoded in the person receiving them. To make the imperatives sensible, people also interpret them through previously learned cultural experiences and values. Thus, if one is raised in a primarily Christian environment, any direct experience of the divine will often tend to take on Christian forms and symbols.

All these things—sensory memory bits, linguistic and cultural structures that give the experience of the sacred memory form—become symbols that contain in themselves the capacity to reinvoke the original sacred experience. Though these elements are used, the sacred does not become only those things. Inherent in the experience of the sacred is the memory of its transcendent nature, and according to their capacity, humans are forced to generate more powerful constructs out of their own existing structures to encompass the immense morphology of the sacred. In this process it is not possible for the human to retain the full experience of the sacred. It is too large a territory. Even so, the human has been changed, is no longer only secular, and the symbols retained point the way to something other and more REAL than the human.

Within many cultures, the search for personal contact with the sacred is an integral part of our maturation and development. When contact with the sacred occurs, its nature and content shape the direction of that person’s life. It provides meaning by which that person determines ethical and honorable behavior and life’s work. Further, frequent contact with the sacred through personal visionary experience or community ritual gives direction for the deepening of one’s own spirituality over time.

Though experiences of the sacred cover a wide spectrum of styles, the oldest and most widespread is Earth centered, or what is sometimes referred to as pagan religion or nature mysticism.

Earth-Centered Spirituality

To Earth-centered peoples the sacred is immediate. It is present in all parts of the world and one may, simply by being willing to be in relationship with the deeper aspects of a part of the Earth, attain closer relationship with Spirit. Through this closer relationship can come knowledge that gives guidance and meaning to one’s life and community. Through this deeper relationship over time one can gain power to evoke the sacred through ceremony, to shape its course into human affairs to benefit the community, to heal and instruct, to uplift.

For those on the Earth-centered spiritual path, the Earth itself is the place of worship; all things possess a soul, every tree, stone, and root. To those in relationship with Earth, the Earth and each part of the Earth is a manifestation of the sacred, a creation of Spirit. Both the whole of Earth and each part of it can manifest itself as the ganz andere, the totally other.6 Within Earth-centered cultures the stone and the tree are venerated as an expression of the sacred, a creation of God. Oftentimes, either through ritual...