![]()

PART ONE

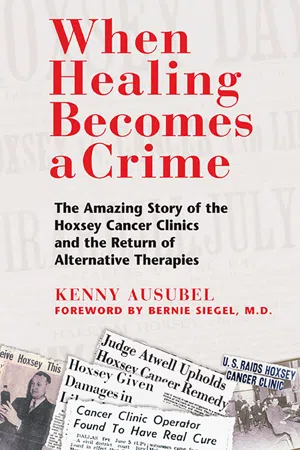

The Wildest Story in Medical History

The Ballad of Harry and Mildred

“Harry fought ’em longer and harder than anyone, but politics is bigger than one man any day.”

Mildred Nelson

![]()

1

Riding the Cancer Underground

In 1840 Illinois horse farmer John Hoxsey found his prize stallion with a malignant tumor on its right hock. As a Quaker, he couldn’t bear shooting the animal, so he put it out to pasture to die peacefully. Three weeks later, he noticed the tumor stabilizing, and observed the animal browsing knee-deep in a corner of the pasture with a profusion of weeds, eating plants not part of its normal diet.

Within three months the tumor dried up and began to separate from the healthy tissue. The farmer retreated to the barn, where he began to experiment with these herbs revealed to him by “horse sense.” He added other popular ingredients from home remedies of the day and devised three formulas: an internal tonic and two external preparations. He soon became known for treating animals with cancer and tumors. Folks said he had “the healing tetch.”

The empiricist handed the secret formulas down through the generations. His grandson John C. Hoxsey, a veterinarian in southern Illinois, was the first to try the cancer remedies on people, and claimed positive results. His son Harry showed an early interest and began working with him. After his father’s death, Harry founded the first Hoxsey Cancer Clinic in 1924, heralded by the local chamber of commerce and high school marching bands on Main Street.1

So begins the Hoxsey legend, and with it the thirty-five-year cancer war between organized medicine and the folk healer. Orthodox medicine branded Hoxsey the worst cancer quack of the century. He would be arrested more times than any other person in medical history.

Yet by the 1950s Hoxsey’s stronghold in Dallas, Texas, grew to be the world’s largest privately owned cancer center, with branches spreading to seventeen states.2 Two federal courts upheld the therapeutic value of the treatment.3 Even his archenemies the American Medical Association and

the Food and Drug Administration admitted that the therapy does cure certain forms of cancer.4

Nevertheless, medical authorities denied Hoxsey’s insistent plea for a fair scientific test. Instead they worked to ban the treatment, outlawing it entirely in the United States in 1960.5 Hoxsey’s chief nurse, Mildred Nelson, took the treatment to Tijuana in 1963, abandoning any hope of offering it in the United States.6

When I first stumbled upon Hoxsey in 1980, I saw it as a sleeping giant of a story that somehow submerged from view after the clinic’s demise. I had a far more personal motive, however, for taking a serious interest. One evening in 1976, over dinner at the small farm where I was living north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, I got a phone call from my mother. My father had cancer. Six months later, at age fifty-five, he was dead.

About two weeks after my father’s death, I received a newsletter in the mail unbidden. It contained testimonials of cancer patients who swore that a complex nutritional program developed by dentist Donald Kelley cured them after their doctors gave them up to die. I read with shock, amazement, and disbelief.

Like many people in 1977, I believed what the doctors told me: Cancer was largely incurable. I certainly knew nothing of alternative treatments. I was skeptical, even hostile, to the idea, but with my father freshly buried and my heart broken, I was open. If there was anything at all to this, I had to know.

I started reading everything I could get my hands on and spoke to anyone I could find who had a direct personal experience. I quickly discovered a subterranean netherworld of purported cures using a variety of therapies—from nutrition and mental imaging to herbs and immunology. It was only when I came across an obscure article about the Hoxsey Cancer Clinics that a lightbulb flashed in my head, illuminating the warp I found myself in. The article by Peter Barry Chowka detailed the astonishing social history of Hoxsey.7 I began to realize that, like most human affairs, medicine is political. Had ideology buried science without an obituary? Were “unorthodox” treatments being politically railroaded instead of scientifically tested?

Chowka’s piece mentioned Hoxsey’s autobiography, and I set out to find a copy. I located it by mail order, and when the self-published book, You Don’t Have to Die, finally arrived, I sat down to scan it. For the next four hours, I read transfixed.

Hoxsey revealed a hidden history of the AMA and U.S. medical politics. He described a venal culture of tyranny and corruption, a medical dictatorship supported by avaricious vested interests. He accused an AMA official of unsuccessfully trying to buy his formulas before subsequently blackballing him.

Would spurned medical politicians suppress a cure for cancer? The seemingly outrageous charge represented nothing less than a crime against humanity. Was it to be believed?

I was a budding filmmaker at the time, and decided to channel my interest in alternative medicine into movies. After my wife illustrated a book about southwestern herbs, I became friendly with the herbalist author and ended up producing my first documentary, Los Remedios: The Healing Herbs, about the rich legacy of plant medicine in the Southwest. A friend showed the program to Catherine Salveson, a registered nurse with a background in cancer care, herbs, and media. Over lunch, I shared with her the story of Hoxsey. Catherine, who even in her nursing uniform bore an uncanny resemblance to singer Joni Mitchell, turned out to be extremely bright, articulate, and open. We connected strongly, and by the end of the meal, we resolved to make a trip to the Tijuana clinic to see for ourselves. Perhaps we would find a film there.

I carried a great deal of trepidation as we set out for San Diego. My only direct experience with cancer had been the horror of my father’s death. Visiting him in Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, the flagship of conventional cancer treatment, branded my psyche with the in-delible imprint of a medical concentration camp. Hopeless patients in blue smocks hovered like phantoms, their emaciated bodies ravaged by radiation and chemotherapy. A skeletal cluster of bald-headed children looking strangely like old men and women formed a macabre audience around a color TV spewing out violent cartoons and commercials for sugar-coated cereal. The place smelled of death and despair. The doctors, aloof and cold, seemed to have hardened themselves against the incredible pain and their own helplessness.

Flying into San Diego, Catherine and I stayed at the “cancer motel” at the edge of the U.S. border. In the morning we boarded the van taking patients to the various Mexican cancer clinics. The mood was somber and anxious. Raul, the Mexican driver, kept up a steady stream of cheerful patter, trying to ease the grim disquietude. As a hospice nurse, Catherine had more equanimity than I did. The van cruised easily through Mexican customs and we entered another country. The only images in my mind of Tijuana were bare lightbulbs and dirty needles.

Climbing steep hills overlooking the city, we arrived early at the Bio Medical Center, as the Hoxsey clinic was now known. Raul pushed back giant wrought-iron gates and shepherded us into the tiny cafeteria to wait for the clinic to open. The huge white building was an elegant Greco-Roman anomaly with large pillars at its carved wooden front doors. Cheerful yellow-and-white-striped canopies shaded the fancifully curving walk-ways. Brilliant tropical birds sang noisily in a big cage in the welcoming courtyard. An empty swimming pool displayed an enigmatic tiled emblem: a painted horse’s head. I had always loved Mexico, and the place felt good.

The Bio-Medical (Hoxsey) Center moved to Tijuana in 1963

The huge front doors swung open and I caught the eye of an older woman. Spontaneously, we smiled broadly at one another. I realized it was Mildred Nelson, with whom I had spoken briefly by phone before arranging to come to the clinic. When Catherine and I introduced ourselves, Mildred became brusque. She was very busy. If we wanted to know the real story of Hoxsey, she said, go talk with the patients. Trailed by an entourage of clinic staff, Mildred moved so swiftly that she seemed to walk through walls, vanishing down a long hallway before we could open our mouths to respond. It was certainly not the reception we planned after months of anticipation and preparation.

We wandered into the waiting room, which was filling with yet another vanload of patients. We were on our own. The spacious room looked out grandly through large plate-glass windows across the sprawl of bustling Tijuana. Sunlight ignited the buzz of early-morning activity as medical orderlies started taking blood and performing other tests. The mood was definitely not what we expected. People laughed, joked, and circulated freely. As the day wore on, we came to recognize the new patients. They were the ones looking distressed and depressed. As the hours passed, they shared the same experience we did, listening to countless older Hoxsey patients cheerfully tell how Mildred had cured them three, five, and twenty years ago. And healed their mothers, their neighbors, and their best friends. Even their dogs. A few said they’d been cured in Dallas in the ’50s by Harry Hoxsey himself.

We were stupefied. The stories were miraculous and they were legion. They involved almost every type of cancer, including the most deadly forms such as pancreatic, lung, and melanoma. Many people complained bitterly of prior abuse by doctors in the States, such as one lady who told how the doctor had removed one-and-a-half lungs, charged $100,000, and then informed her he hadn’t expected it to work anyway. We also heard several accounts of relatives who had died while trying Hoxsey, but who experienced a relief of pain pronounced enough to stop taking painkillers.

The treatment was inexpensive, too. Mildred then charged a one-time fee of $1,500. Many patients paid in installments as low as $5 a month, and those who were destitute paid nothing. In his book, Hoxsey said that this tradition came from his father’s deathbed charge that no patient be turned away for lack of funds.

Riding the van back to the cancer motel that afternoon, we found the mood decidedly upbeat. The passengers laughed uproariously at the idea of writing a cancer patients’ joke book. Raul became serious, however, as we waited in line to cross the U.S. border. He carefully instructed us exactly how to answer the question of what we were bringing back from Mexico. “Just say ‘herbs and vitamins,’” he cautioned with sudden sobriety. “Do not say ‘drugs.’ Just herbs and vitamins.” The blocky border guard scowled inside the van. He asked a couple of people to open their little brown bags carrying the Hoxsey tonic and vitamins. Grudgingly, he let the van through. The effervescence went flat. We all knew we had crossed not just a political boundary, but a philosophical border as well.

After a couple of more days at the clinic, Catherine and I passed the better part of Memorial Day weekend holed up with Mildred in her small trailer next door where she had lived since coming to Tijuana. A once mobile home, it was now stationary atop the tiny pharmacy that originally served as the first Bio Medical Center. According to rumors, the beautiful new clinic next door was a former house of ill repute whose señora got busted on narcotics charges. Mildred put in an improbably low bid on the repossessed estate and, to her amazement and delight, she got it.

Imbibing a steady stream of coffee and smoking her trademark long brown cigarettes, Mildred regaled us in her thick Texas twang with countless anecdotes of Hoxsey’s war with the AMA and FDA, stories regularly seasoned with rambling recollections of remarkable remissions. After a while, it became clear to us that Mildred was utterly sincere. She got involved with Hoxsey when her mother was successfully treated in Dallas in 1946 after being given up on by her doctors. Initially hostile, Mildred became a believer.

The phone interrupted constantly, day and night, with the frantic calls of cancer patients from all over the United States, Canada, and the world. Mildred answered every call, no matter what day of the week or time of day. “How would you as a cancer patient like to get an answering machine?” she challenged us sharply. As nurses on the front lines of caring for the sick, Mildred and Catherine understood each other perfectly.

In the course of conversation, we learned chillingly that Mildred had no successor. Sixty-five years old with two strokes behind her, she was searching. Interested doctors had come and gone, but none had the devotion and moxie it would take to preserve the contentious legacy. Because the Mexican government exacted a prohibitive fee of $50,000 a year for working papers for U.S. physicians, Mildred employed solely Mexican doctors, none of whom had the political sav...