- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Twelve Brain Principles That Make the Difference

About this book

Twelve Brain Principles That Make the Difference by Brian Pete and Robin Fogarty, is about how the brain learns best and all the things teachers can do to facilitate the learning part of the teaching scene. This book presents a unique organization of Renate and Geoffrey Caine's twelve brain principles. The twelve principles are arranged in four specific quadrants. Each quadrant speaks to a particular aspect of the high-achieving classroom and highlights how instructional decisions are governed by the twelve principles.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE: CLIMATE FOR LEARNING

Although the Caines make it quite clear that their twelve principles are a systemic set of principles, the authors have chosen to subdivide the twelve into four distinct but interrelated groups: Climate for Learning, Skills of Learning, Interactions With Learning, and Learning About Learning.

The first group of principles under the heading “Climate for Learning” includes three principles that stress both a safe emotional climate and a sensory rich environment. Principle 1, Challenge engages the mind; threat inhibits the cognitive abilities, talks about the role of rigor in the learning environment. Principle 2, Emotions and cognition are linked, addresses the idea that learning is enhanced in an emotionally safe climate. Finally, Principle 3, The brain learns both through focused attention and peripheral perception, speaks to the idea of a learning environment that is both sensory-rich and print-rich, attracting the focused and peripheral attention of the learner.

In sum, all three principles seem to relate to the emotional culture of the learning environment. Is it emotionally safe to take a risk? Are there many stimuli to spark the growth of dendrites?

Challenge/Threat: Learning Principle 1

| Learning Principle 1: | Learning is enhanced by challenge and inhibited by threat. |

A Story to Tell

It is the first day of school and the fourth grade teacher is talking to his class about the upcoming school year. The school, which is in a tough urban neighborhood, has been on probation for three years. The teacher says, “The reading and writing skills and habits that we will work on this year will be important for you when you get to college.”

All of the students look up; many raise their hands. The first student who is called on asks, “How long is college?”

Another asks, “Who can go to college?”

The teacher moves to the side of the room and begins writing on another chalkboard, in a more prominent place. As he moves, students turn in their chairs and follow him with their eyes.

Synonyms—Challenge

Responsibility

Obligation

Duty

Venture

Formidable task

Problem

Synonyms—Threat

Hazard

Intimidation

Fear

Pressure

Anxiety

Concern

As he is writing, he says, “Four years from now you will enter high school (he writes 4 on the board), and then after two years of high school (he writes a 2 on the board), you will begin to consider colleges and universities that you might like to attend. After you graduate from high school (he writes another 2 on the board), you will enter a four-year college (he writes a 4 on the board). The teacher continues the timeline all the way through medical school and then asks, “How many years will it take you to become a doctor?”

A few hands go up, the teacher calls on them, but no one has the answer. Then, in the back row, one boy, who has not spoken at all this first day because of his poor English skills, raises his hand and says, “Twenty years.”

“That’s right!” says the teacher, and all the other students turn and look at the boy in the back row.

Later the same day the teacher is handing papers to the students and as he passes the boy who answered correctly, the teacher leans in and says, “Here you go, Doctor.”

Things You Need to Know

What’s It All About?

Challenge is a test of one’s abilities or resources in a demanding but stimulating undertaking, for example, undertaking a demanding career. Threat is an indication of impending danger or harm, for example, seeing lightning while playing golf.

Challenge

A classroom environment designed for learning has to challenge and at the same time not threaten learners. This may sound like a simple goal, but on the first day of school, as the room fills with children who are together for the first time, the environment can appear threatening. It does not have to. By presenting the new beginning as a challenge, teachers can fire students’ brains and watch them come alive. This human need for challenge is a primal force that teachers can tap. Research on the brain shows that humans like challenge.

This human need for challenge is a primal force that teachers can tap.

When students are challenged with rigorous curriculum, they respond with enthusiasm. Challenge, when presented in a way that allows each student to imagine being “in the game” and able to “bring something to the table,” creates the kind of classroom that fosters student engagement and achievement.

Challenging problems that also have emotional relevance are a natural hook for learning. When students are faced with a problem that has no easy answer, teachers can help them to persevere, become engaged, and work hard to solve the problem.

There are endless stories about someone who has been told that he or she can’t do something—for example, “This problem is for students in the next grade; it’s a level above you”—but succeeds because he or she sees it as a challenge, not an impediment. A well-thought-out challenge from a teacher can engage students, who then work harder than they ever could have imagined they could to achieve their goal.

Threat

The second part of this principle—Learning … inhibited by threat—focuses on the importance of the emotional state of learners as they try to learn. Faced with threat—threat of danger, threat of embarrassment, threat of shame—a human’s brain is dominated by the emotional brain and may not function to its potential in the cognitive realm.

Goleman’s (1995) discussion of emotional intelligence emphasizes that when students feel supported and safe in the classroom, they are more likely to perform to a higher level. On the other hand, students who feel that there is a threat of any kind become emotionally charged, and thus, their cognitive abilities take second place.

A threatening situation may be one in which a student has to give an oral report in front of the class. The student may sabotage her own success just so she can avoid this emotionally threatening possibility. On the other hand, a student member of a cooperative group may rise to the challenge of his role as spokesperson for the group because he knows, as part of the group, that he is not alone and, thus, feels more comfortable and less threatened.

The difference between a rigorous challenge and a threatening situation is both simple and complex.

The difference between a rigorous challenge and a threatening situation is both simple and complex. A challenge might be so tough that learners fail in their efforts and collapse in nervous frustration. This is a rigorous challenge gone awry and turned into a threatening situation. But, when the challenge is structured correctly, learners can find a solution after a reasonable amount of work by using tools they have mastered even though the task is pushing their envelope of skills. These students are challenged but not threatened; they feel safe and even free to risk failure or, at least, temporary failure. This experimenting and stretching of their capacity to understand and make meaning is the best possible way for them to learn.

Students quickly diagnose a poorly designed learning situation as a possible threat, particularly if they see failure as fatal or maiming. If their wrong answers are to be posted on the board for all the class to see, students may not be able to produce the right answer, even though they may actually know it. If the outcome of a test means that they are separated in some way from their peers, students may lose their capacity to process information at peak levels, and they may even sabotage their own chances for success just to feel like they are in control of their own destiny.

Why Bother?

A classroom that challenges students to think with rigor, is the classroom of high expectations (Haycock, 1999). In fact, when low performing schools are staffed with quality teachers who expect rigorous thinking and complex solutions, even the lowest performing students will rise to the occasion (Haycock, 1999). The learner simply cannot resist the look of a good challenge and his or her mind goes into high gear (Sprenger, 1999).

When complex problems are part of the enriched environment, students will encounter, without fanfare and quite naturally, problems that they cannot solve. For example, when intricate puzzles, word games, and brainteasers are a regular part of the classroom, students can interact with them on their own time and in their own way. When they encounter a visual spatial problem, a mathematics quiz, or a hands-on manipulative that they cannot immediately conquer, they have a chance to demonstrate curiosity, even failure, without high stakes. Figure 1.1 suggests kinds of problems and decisions that may be created to challenge rigorously, but also safely and frequently.

| Problem Solving | Decision Making | Creative Ideation |

| Mathematics problem solving | Ethical dilemmas | Science projects |

| Future problem solving | Moral issues | Presentations |

| Olympics of the mind | Values clarification | Persuasive speech |

| Service learning | Character building | Artistic murals |

| Problem based learning | Court decisions | Musical compositions |

| Civic projects | Debating | Map making |

| Choose your own ending | Athletic competition | Conceptualizing a museum |

Figure 1.1. Safe challenges.

A Tiny Transfer to Try

Challenge or Threat: A Fine Line

Attach poster paper to the walls in the corners of the room (if possible). Each poster shows a different challenging puzzle, for example:

1. A Mathematics Story Problem

Rachel has six more brothers than she has sisters, but her brother Ryan has four more brothers than he has sisters. If there are fewer than 10 children in the family, how many boys and girls are there?

2. A Tongue Twisting Poem

Jim had a small baseball card collection. All but five were signed, all but five were rookie cards, and all but five were less than 10 years old. What is the minimum number of cards he could have had?

3. A Geometric Line Drawing

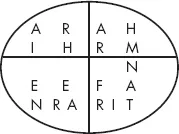

Unscramble the letters in each segment in the “pie.” Find the missing letter that completes each word and is shown by a “?” (use the same letter for each word)

4. A Riddle

Find the word that fits the first definition, and then add an “S” in fron...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part One: Climate for Learning

- Part Two: Skills of Learning

- Part Three: Interactions With Learning

- Part Four: Learning About Learning

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Twelve Brain Principles That Make the Difference by Brian M. Pete, Robin J. Fogarty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.