![]()

Part I

Looking at Literacy in the Graphic Novel Classroom

Page 59, panel 2, from Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud, copyright © 1993, 1994 by Scott McCloud. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins.

![]()

| 1 | Looking at the Comics Medium |

| Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics |

“Today, you guys are going to work in groups. Once you get into groups, elect once person to sit in the hallway. You’ll each get a scenario that the remainder of your group must draw together. You cannot add any words to your drawing! The person you elected to leave the classroom will return when every group is done drawing their scenario on the whiteboard, and this person will try to describe his or her team’s scenario with words. The group whose member provides the most accurate description of his or her group’s scenario wins! Group 1, here’s your scenario: a blind man mowing his lawn while his seeing-eye dog relaxes in a hammock. Group 2: a hippie fish protesting a polluted lake. Group 3: . . .”

—Ms. Bakis

James Sturm’s “Think Before You Ink” game is one of the fun, constructive activities I use in the graphic novel classroom to engage students in learning about how to use pictures to communicate and to reinforce the aspects of visual literacy found in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1993). If you want to learn how to read a graphic novel by understanding the ins and outs of the comics medium, McCloud is the place to begin, though I also highly recommend Will Eisner’s Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative (2008), especially if you are new to graphic novels or are teaching younger students. Eisner provides excellent background in storytelling basics, visual storytelling, the notion of empathy, and use of stereotypes. The reading assessment I use with my students for this text is provided at the companion website (www.corwin.com/graphicnovelclassroom) and highlights the main ideas and concepts about comics and storytelling I like my students to become familiar with before reading graphic novels.

I teach Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics to help students understand and develop an appreciation for the important role of graphic art, visuals, and other media as communicative tools, as well as to more consciously realize their own role as constructive readers and communicators. McCloud reinforces the interdependent relationship of images and words that prompts students to get beyond the stereotypical perception of the role of images in graphic novels as supplementary or in service to a more important story told in words. Understanding Comics is also a useful tool in helping students exercise visual literacy while reading graphic novels and develop a critical language to better evaluate them beyond their literary merit. Understanding the relationship between form and content is crucial, which is why we begin with McCloud.

TEACHABLE TOPICS, CONCEPTS, AND SKILLS

Table 1.1 highlights important topics and skills associated with teaching Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.

FRAMING THE TEXT

I engage students in Understanding Comics by presenting background about Scott McCloud using a TED Talk video featuring the author (McCloud, 2005). Using the interactive whiteboard to project our course social network site, I also bring students to McCloud’s website (www.scottmccloud.com) to read his interactive, online comics narrative called “My Number” and his blog, to look at his work for Google, and to peruse the other resources available to aid their understanding of comics throughout the unit.

Since this is a nonfiction, information-heavy text, as students read chapters of Understanding Comics, I ask them to respond to study guide questions for homework to gauge their initial, independent comprehension of concepts before reviewing and applying them in class activities. The study guide is located at the companion website.

Table 1.1 Teachable Topics, Concepts, and Skills in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics

| Topics and Concepts | Skills |

| Iconography | Visual literacy |

| Closure | Reading comprehension (nonfiction) |

| Comics defined and sequential art | Acquiring and using new vocabulary |

| Understanding media | Awareness of reading process |

| Storytelling | Active, constructive reading |

| Human communication | Discussion |

| Consciousness of audience | Illustration and drawing |

| Panels | Metacognition |

| Panel transitions | Applying new concepts |

| Gutters | Identifying comics concepts |

| Bleeds | Problem solving |

| Balance of pictures and words in comics | Critical viewing |

| Time, sound, and motion in comics | Critical reading |

| The picture plane | Analysis |

| Art defined and the artistic process | Critical thinking and evaluation |

| Comparison of Eastern and Western comics | Making inferences |

| Color and comics | Making comparisons |

| Lines, emotions, and expressionism | Examining assumptions and preconceptions |

| Blurring | Drawing conclusions |

| Zip lines | Collaboration and cooperative learning |

| Streaking | Innovation and creativity |

DEFINING COMICS

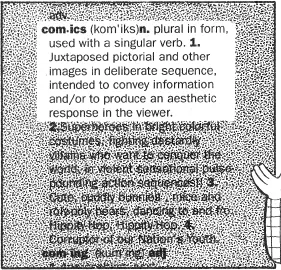

We begin our classroom exploration of Chapter 1 of Understanding Comics by reviewing McCloud’s brief history of comics, which is based on the way he defines the medium:

My students’ compare their initial understanding of how they personally define comics with McCloud’s definition, noting similarities and differences. Like the initial J. P. Toomey TED Talk video (2010), McCloud’s broad definition helps to show students that comics encompass far more than what they initially determined in their original definitions. Making sure students understand the meaning of aesthetic (McCloud, 1993, p. 9) is critical in understanding McCloud’s definition, as well as emphasizing the fact that McCloud does not use the term words in his definition. Contrasting the meaning of aesthetic with its opposite, anesthetic, is one way to do this, for it allows students to put their new knowledge into terms already familiar. Just as empathy is an important part of how readers relate to story, so too is aesthetic response vital in reading sequential art. McCloud later explains in Chapter 2 how words are part of the “other images” (p. 9) given in his comics definition by calling words abstract icons. To emphasize this aspect of the definition, I draw the same example McCloud gives on page 46 in panels 4 and 5 on the whiteboard for students. Contrasting the definition of comics McCloud provides with definitions of genre and art is another important part of teaching Chapter 1 of Understanding Comics. Magnifying the illustration of the water pitcher on page 6, panel 1, is a good way to display this concept clearly for students. Because students often confuse comics as another genre of literature, the distinction is important. Jessica Abel and Matt Madden’s Drawing Words & Writing Pictures (2008) provides an excellent explanation of comics as a medium that also may be useful for classroom instruction.

Page 9, panel 5, from Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud, copyright © 1993, 1994 by Scott McCloud. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins.

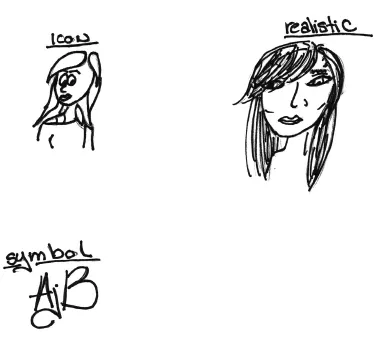

LOOKING AT REPRESENTATION, ICONS, AND IDENTITY

Representation is a key concept in Chapter 2 of Understanding Comics and is shown most clearly in McCloud’s famous “The Treachery of Images” (p. 24–25) example, where the degree to which an idea or object is represented influences the reader’s ability to comprehend its meaning. Also in Chapter 2, the distinction between abstract ideas and sensory objects is important in understanding the variety of ways artists convey story using these tools. The reader’s participation in meaning-making by recognizing and interpreting the manner in which a person, place, thing, or idea is conveyed using lines and space is another important concept in Chapter 2. To reinforce McCloud’s definition of icon on page 27, my students draw realistic and more iconic representations of themselves, as well as symbolic representations, during class (see below). Students draw examples on the whiteboard and we discuss levels of abstraction.

An alternative lesson might be to display various examples of icons in a slideshow presentation and have students answer aloud to which category each belongs, or students might search online for visual images and categorize them according to McCloud’s definitions.

Participation: How Much of You Is in What You See?

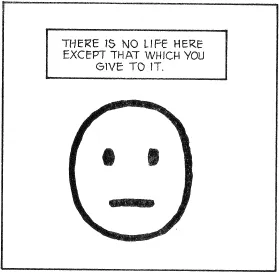

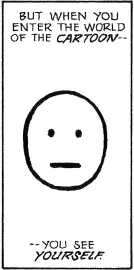

The image on page 36 of Understanding Comics refers to reader participation, insofar as we see ourselves and extend our identities into iconic images. According to McCloud, this is a typically human response and part of the way we give meaning to what we see. My students are especially intrigued by this concept and connect it to the idea of empathy previously introduced in Eisner’s Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative.

The less defined the images (the more cartoony), the better able we are to see ourselves or impose ideas and visions of ourselves into such a broadly defined image. McCloud proposes that this also gives us an opportunity to fantasize and play with such conjured visions of ourselves. Another way to understand this is to think of it as the way in which comics art invites readers to be “in” the story, therefore fostering more intimate engagement with the text. Abbey’s understanding of this concept is evident in her reading response below:

Cartoon faces are generalized, so that they could represent anybody. It makes it easy for the audience to insert themselves into the story, which amplifies the overarching meaning of the story. A character drawn too specifically is too distant from the audience.

The degree of empathy depends on how intimately connected the reader feels to what he or she sees while reading. If we can imagine ourselves in a broadly defined image, chances are greater that we will feel as though we are in the story, a technique comics artists regularly exploit. My hope is that students will learn to exploit this technique in their own compositions as well.

Page 36, panel 4, from Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud, copyright © 1993, 1994 by Scott McCloud...