![]()

Chapter 1

Handling Social Misbehavior

THE SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL BRAIN

“I was so angry, I couldn’t think straight!” “He got me so mad, I nearly hit him!” Both of these statements make it clear that emotions were running high. Human beings have been interacting with emotions for thousands of years, but understanding where they come from and how they direct our behavior is still not fully understood. Nevertheless, thanks to the development of brain imaging techniques, researchers have made substantial progress in discovering the underlying neural networks that encourage and inhibit certain behaviors. After all, we are not just information processing machines. We are also motivated, social, and emotional beings who are constantly interacting with our environment. Schools and classrooms are particularly demanding environments because so many different personalities gather together in a confined area where they are expected to interact according to established rules of accepted emotional and social behavior.

Schools and classrooms are demanding environments because so many different personalities gather together in a confined area where they are expected to interact according to established rules of accepted emotional and social behavior.

So what is happening inside the brain of students who display socially unacceptable behavior? Are these just temporary responses to a particular situation or are they symptoms of an underlying disorder? Do we immediately refer the student for mental evaluation or try a classroom intervention that may improve the behavior? These are difficult questions. But before we can answer them, we need to review some of what scientists know about how emotions are processed in the brain. The purpose here is not to make educators into neuroscientists. But the more teachers know about how the emotional brain works, the more likely they are to choose instructional strategies that will lead to appropriate student behavior and successful student achievement.

Emotional Processing

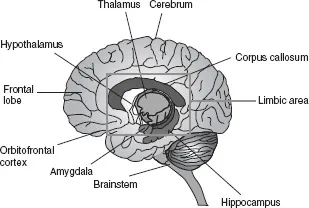

Long before the advent of brain imaging technology, researchers in the 1950s suggested that the structures responsible for processing emotions were located in the mid-brain, an area that Paul MacLean (1952) described as the limbic system (Figure 1.1). His work was very influential and the term “limbic system” persisted and continues to show up in modern texts on the brain. However, current research does not support the notion that the limbic system is the only area where emotions are processed, or that all the structures in the limbic system are dedicated to emotions. Brain imaging shows that the frontal lobe and other regions are also activated when emotions are processed, and limbic structures such as the hippocampus are involved in nonemotional processes, such as memory. In light of these newer discoveries, the trend now is to refer to this location as the “limbic area,” as we have in Figure 1.1.

MacLean also described the frontal lobe (lying just behind the forehead) as the area where thinking occurs. We now know that the frontal lobe comprises the rational and executive control center of the brain, processing higher-order thinking and directing problem solving. In addition, one of its most important functions is to use cognitive processing to monitor and control the emotions generated by limbic structures. In this role, the frontal lobe is supposed to keep us from doing things when we are angry that we would regret later, and from taking unnecessary risks just to indulge emotional curiosity or please others.

Development of the Brain’s Emotional and Rational Areas

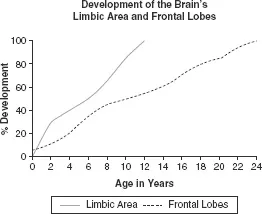

Among other things, human survival depends on the family unit, where emotional bonds increase the chances of producing children and raising them to be productive adults. The human brain has learned over thousands of years that survival and emotional messages must have high priority when it filters through all the incoming signals from the body’s senses. So it is no surprise that studies of human brain growth show that the emotional (and biologically older) regions develop faster and mature much earlier than the frontal lobes (Paus, 2005; Steinberg, 2005). Figure 1.2 shows the approximate percent development of the brain’s limbic area and frontal lobes from birth through the age of 24 years. The limbic area is fully mature around the age of 10 to 12 years, but the frontal lobes mature closer to 22 to 24 years of age. Consequently, the emotional system is more likely to win the tug-of-war for control of behavior during the preadolescent years.

Figure 1.1 A cross section of the human brain showing major structures and highlighting the limbic area buried deep within the brain.

What does this mean in a classroom of preadolescents? Emotional messages guide their behavior, including directing their attention to a learning situation. Specifically, emotion drives attention and attention drives learning. But even more important to understand is that emotional attention comes before cognitive recognition. For instance, you see a snake in the garden and within a few seconds your palms are sweating, your breathing is labored, and your blood pressure is rising—all this before you know whether the snake is even alive. That’s your limbic area acting without input from the cognitive parts of the brain (frontal lobe). Thus, the brain is responding emotionally to a situation that could be potentially life-threatening without the benefit of cognitive functions, such as thinking, reasoning, and conscious ness (Damasio, 2003).

Figure 1.2 Based on recent studies, this chart suggests the possible degree of development of the brain’s limbic area and frontal lobes.

Source: Adapted from Paus, 2005, and Steinberg, 2005.

Preadolescents are likely to respond emotionally to a situation much faster than rationally. Obviously, this emotional predominance can easily get them into trouble. If two students bump into each other in the school corridor, one of them may just as likely respond with a retaliatory punch than with a “sorry.” On the positive side, this emotional focus can have an advantage when introducing a lesson. Getting the students’ attention for a lesson will be more successful when they make an emotional link to the day’s learning objective. Starting a lesson with “Today we are going to study fractions” will not capture their focus anywhere near as fast as asking whether they would rather have one-third, one-fourth, or one-sixth of a pizza. Whenever a teacher attaches a positive emotion to the lesson, it not only gets attention but it also helps the students to see real-life applications.

The Orbitofrontal Cortex: The Decision Maker

As investigations into emotions have become more extensive, it is clear that emotions are a complex behavior that cannot be assigned to a single neural system. Instead, different neural systems are likely to be activated, depending on the emotional task or situation. These systems might involve regions that are primarily specialized for emotional processing as well as regions that serve other purposes. However, two brain areas whose prime function appears to be processing emotions are the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala (Gazzaniga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2002).

The orbitofrontal cortex is at the base of the frontal lobe and rests on the upper wall of the orbit above the eyes (Figure 1.1). Research of this brain area indicates that it regulates our abilities to evaluate, inhibit, and act on social and emotional information. Exactly how this regulating effect works is still not fully understood, but imaging studies continue to provide clues. Brain scans reveal that a neural braking mechanism is activated for a few milliseconds (a millisecond is 1/1,000th of a second) when adults are asked to make a decision based mainly on an emotional stimulus. The braking signal is sent to a region near the thalamus (see Figure 1.1) which stops motor movement. A third brain region initiates the plan to halt or continue a response. The signals among these brain areas travel very fast because they are directly connected to each other. In this process, putting on the brakes may provide just enough time for the individual to make a more rational and less emotional decision (Aron, Behrens, Smith, Frank, & Poldrack, 2007). However, the less mature the regulating mechanisms are, the less effective this braking process can be. As a result, the abilities regulated by the systems in the orbitofrontal cortex essentially form the decisions we make regarding our social and emotional behavior.

The brain’s frontal cortex activates a braking mechanism that halts movement for a few milliseconds to allow an individual to decide what action to take in response to an emotional stimulus.

Social Decision Making. One way in which we make decisions is to analyze incoming and internal information within a social context and then decide what action to take. For example, we might be so upset by something that we just want to shout out a cry of disgust. But if at that moment we are riding on a packed bus or walking through a crowded shopping mall, the social context (Will these people think I’m insane?) inhibits us from doing so. In schools, students often refrain from doing what they really want for fear of what their peers will think of their behavior. For instance, some students regrettably do not perform to their potential in school because they fear that their peers will think of them as nerds or teacher’s pets and thus ostracize them from their social group. On the other hand, students sometimes perform risky behaviors (e.g., underage drinking, reckless driving) just to get their peers’ attention. Social context, therefore, is a powerful inhibitor or encourager of behavior.

Social context is a powerful inhibitor or encourager of behavior.

People with damage to the orbitofrontal region have difficulty inhibiting inappropriate social behavior, such as unprovoked aggressiveness, and have problems in making social decisions. Also, although they fully understand the purposes of physical objects around them, they often use them in socially inappropriate ways. For example, a student with this deficit knows well that a pencil is for writing, but may be using it to repeatedly poke others.

Emotional Decision Making. Because social cues often give us emotional feedback, how we act in a social context cannot easily be separated from how we evaluate and act on emotional information. Nonetheless, experimental evidence suggests that the orbitofrontal cortex evaluates the type of emotional response that is appropriate for a particular situation. Sometimes, this means modifying what would normally be an automatic response. For example, think of a toddler eyeing a plate of chocolate chip cookies. If the child is not allowed to have one, the frustration could well cause the child to throw a fit and physically display anger by kicking and screaming. His brain’s frontal lobes have not developed sufficiently to moderate the impulse. Thus the child readily shares his emotions with everyone around him. Now an older child in the same situation might feel like throwing a fit but his frontal cortex has developed further and moderates the impulses. Head injury, abuse, alcoholism, and other traumatic events can interfere with the brain’s ability to moderate emotions, resulting in a more primitive level of behavior inconsistent with the child’s age.

Here’s another example. We generally laugh out loud at a really funny joke. But doing so, say, at a lecture or in church would not be the emotionally appropriate action. Thus, the orbitofrontal cortex quickly evaluates the social situation and overrides the typical response of loud laughter (Rolls, 1999). To perform this function successfully, the orbitofrontal cortex has to rely on learned information from other brain structures. One of those structures that interacts with the orbitofrontal cortex is the amygdala.

The Amygdala: A Gateway for Emotional Learning

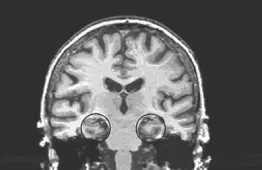

The amygdala (Greek for “almond,” because of its shape and size) is located in the limbic area just in front of the hippocampus, one in each of the brain’s two hemispheres (Figure 1.1). Figure 1.3 shows the location of the amygdala on each side of the brain. Numerous studies have indicated that the amygdala is important for emotional learning and memory. These learnings can be related to implicit emotional learning, explicit memory, social responses, and vigilance. Let’s briefly explain each of these.

Figure 1.3 The circles show the location of the amygdala in the brain’s left and right hemispheres.

Implicit Emotional Learning. Suppose a student lives ...