![]()

1

The Three D’s of Success

Slightly overweight and somewhat awkward, Shawn liked video games more than real games, even though he wasn’t very good at either. After school he went downstairs, closed his bedroom door, chose a game on his computer, and tried to make it to the next level. He didn’t feel comfortable with most people, especially adults. He hated his fourth-grade teacher. She just asked him to do things he didn’t want to do. Like reading. Computer images he could handle, but words were not his thing. Still reading on the first-grade level, books were intimidating, and his life didn’t get much better as he went from elementary to secondary school. We actually met him when he was nineteen. We asked him one day if he had ever succeeded at anything—“skateboarding, skiing, anything?” Afraid to look us in the eye, he mumbled, “No.” We then told him that his days of constant failure were over: “You’re going to see what it feels like to succeed.”

Shawn is like so many of our young people. Each year the Commissioner for the National Center for Educational Statistics produces a report about the state of education in the United States. In the spring of 2007 his report showed that fourth and eighth graders’ reading ability has varied little during the past fifteen years. Fewer than one-third of the students performed at the proficient level, and twelfth graders’ reading performance has decreased significantly, from 40 percent to 35 percent at the proficient level.

Likewise, fully 39 percent of these twelfth graders in 2005 performed below the “basic” level in mathematics. This means that at the end of their high school education these students did not even possess “partial mastery of fundamental skills.”

How did students do in science? Quite similarly. The fourth graders showed some improvement during the past ten years, the eighth graders stayed the same, and the twelfth graders did worse. So it appears that even when students show slight gains in the early grades in reading, math, or science, those gains eventually lead to deficits by the time the students graduate from high school (see Schneider, 2007).

What happens to students as they complete a college education? Again, the data are deeply disappointing. Romano (2005) laments that only 31 percent of college graduates in 2003 read at the proficient level, significantly down from 40 percent ten years earlier. The one clear conclusion from all the data on education, the No Child Left Behind Act, and undergraduate education in the United States is that we are not improving. Policies and programs the nation has implemented to raise literacy rates in reading, math, or science are not working. In short, most students are not succeeding. Many are graduating and getting degrees, but they are not succeeding, because their desire to learn has weakened and diminished rather than grown stronger and brighter.

We argue that addiction to failure is one of the primary causes of such disappointing results from our system of education. Shawn was obviously addicted to failure. He did not expect to succeed at anything he tried. There may have been some teachers in his life who were also addicted to failure—teachers who did not expect to succeed with Shawn when he was in their class. There might also have been parents, administrators, and policymakers with similar addictions. Why? Because they were not experiencing success in their role—whatever that role was. Those in leadership positions who develop addictions to failure express their frustration in cynical remarks.

A Chinese student once asked me to define the word cynic. I read her the dictionary definition: “one who believes that human conduct is motivated wholly by self-interest” (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition). A cynic is someone who always focuses on the negative. Cynics, in fact, are addicted to the negative. One of our favorite remarks about cynicism follows: “When I was a young man and was prone to speak critically, my father would say: ‘Cynics do not contribute, skeptics do not create, doubters do not achieve’” (Hinckley, 1986, p. 2).

Students can fall prey to cynicism but so can teachers and educational leaders. Just listen sometime to educators talk about the policies that govern their practice. The policies might be at the school, district, state, or national level, but rather than focusing on legitimate flaws in a policy and suggesting strategies to improve it, the conversation often turns toward hopelessness and pessimism.

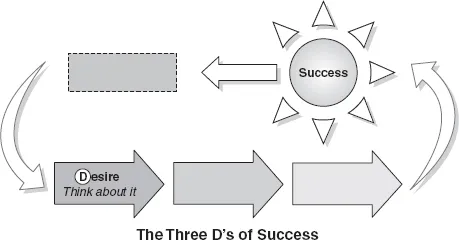

What we offer in this chapter is an alternative to cynicism, a way out of negativism, an antidote for failure: we call it the Three D’s of Success—desire, decision, and determination. We are convinced that when teachers, students, and leaders practice the Three D’s, addictions to failure and negativism gradually disappear, and learning for everyone—both students and teachers—increases.

DESIRE

The first “D” in the success equation is desire. As Mager and Pipe (1997) put it, “you really oughta wanna.” If students don’t want to learn, they won’t learn. If teachers don’t want to improve, they won’t improve. If leaders don’t have the will to change and help others change, everything will remain the same or worsen. Desire must be present. The word desire, however, can be viewed in several ways. Many focus on its emotional meaning—a longing, a yearning, an attraction. We define desire quite differently.

When we speak of desire in this book, we are emphasizing the end result of the word. For us the most apt synonym for desire is the word goal. The person wants to do something or be something. A student might want to learn how to read well enough to read the Harry Potter books. This is a definitive goal, and the goal itself is the best expression of the student’s desire. Using this definition, the word desire is no longer simply an emotion that we cannot get our arms around. It’s a thought, an aim, a determiner of personal conduct. Figure 1.1 shows that desire is the beginning of success.

Notice that below the word desire is the phrase Think about it. Whatever a student or teacher is thinking about is the most powerful determinant of what that student or teacher will do. “We are always moving in the direction of our most dominant thought” (Waitley, 1985, p. 126). Another way of saying that is: “Our thinking determines our behavior.” The thing we desire most or think about most—our goal—will always drive our actions. So when a student laments, “I really don’t have any desire. I don’t want to do anything right now,” as educators we should not believe the student. It’s actually not true. The student wants to do something. We just don’t know what that something is, and the student might not know either. The only way to proceed is to go to the next step in the three D’s—to help the student decide to do something.

Figure 1.1 Desire

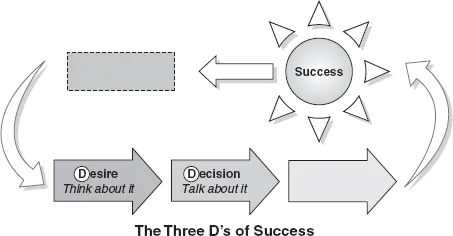

DECISION

A teacher typically reacts to a student who is lethargic by trying to identify the underlying cause of the malaise—then, supposedly, desire will increase and the student will be reenergized. We assert that there is a more effective way of motivating seemingly impossible to motivate students: helping them do the task at hand, helping them decide to perform—even if they don’t feel any desire at the moment. The principle upon which the Three D’s is built is that desire will increase following success. The idea is akin to what Albert Bandura calls “the empowerment model” (Evans, 1989, p. 16). So as educators we don’t need to waste time trying to pump up students’ desire while waiting for them to become engaged in the learning task. The learning task itself—if it is designed effectively—will do the pumping up automatically. Helping students set goals that they want to achieve is much easier than psychoanalyzing each student’s lack of desire.

So once students have defined the goals they want to achieve, they then must decide to achieve them. The student who wanted to improve his reading ability so he could read a Harry Potter book must now decide to do things that will lead to the achievement of that goal. This is where the educator has the most power to influence learning: helping the student set realistic, appropriate learning goals that will lead to the accomplishment of the student’s desired outcome. Bandura (1994) calls this type of instruction “guided mastery.”

Students who are addicted to failure never really decide to do anything. They sit and wait for the teacher to direct them. Teachers or educational leaders who are addicted to failure likewise avoid making the decisions they need to make (decisions that involve risk) because they are afraid of failure. For example, they implement district or state mandates without deciding how those mandates can actually benefit specific students in their classroom or school. Figure 1.2 shows that decision is the second step toward success.

A noneducation example helps illustrate our point. The American Heart Association (2007) reports that more than four out of five smokers wish they could quit. So when they say, “I’m addicted,” a friend might ask: “Do you really want to stop?” “Oh yes, but I’ve tried, and I can’t.” The next question the friend could pose is: “Have you ever actually decided to stop?” Most smokers will admit that they can’t bring themselves to make the decision. One smoker described it to us this way, “There’s still something inside me that wants to keep smoking.” In other words, “I can’t go against my own desire, so I just won’t make the decision to stop, because there’s always the chance that my inner desire might take over again and cause me to smoke.” As Schaler (2000) asserts in his book by the same title, “Addiction is a choice.” We recognize that genetic tendencies can predispose people to certain types of addictions, but we assert that people still have power over their own conduct. They can choose to overcome an addiction to failure. They can choose to succeed.

Figure 1.2 Decision

Students and teachers are not very different from the smoker who avoids making a decision to quit. Every human being is born with a powerful inner strength: the power to choose, or the power of personal agency. It is the most important attribute anyone possesses. A student can choose to focus her attention on the teacher or on a book or on a text message that just arrived. A teacher can choose to focus his attention on helping a student overcome a hurdle or on how to avoid the next inservice meeting. The power of choice is always with us, and that power is far greater than most realize. When one exercises this inner power, one begins talking about it, as shown in Figure 1.2. Decision making is more than the thought process identified in the desire stage of the Three D’s. When we make a decision, we eventually share it with someone else.

The example of Shawn, the young adult with a reading disability, points to the power of talking about one’s decision. He had to decide to change. He had to decide to submit himself to a peer tutor who wanted to help him. He had to decide to try, and not until he made those decisions public (to “talk about it” with his tutor and others), did he see any success. Deciding can be a scary thing. When anyone decides on a new course of action, an old way of being must be left behind. After becoming more proficient in reading, Shawn could no longer describe himself as “disabled.” He might still have felt the effects of learning problems he had suffered in the past, but he could no longer accept sympathy from others because of his difficulty with reading. Why? Because he became more proficient at the task. He decided to change. He exercised his personal power of agency to do something different and to be someone different. As he made these decisions, he began talking to others about them.

In this book, when we discuss personal agency or the power to choose, we are talking about a particular kind of choice making. Educare, the Latin root of the word education, means to “draw out.” The process of education, then, is to draw out the good that is already inside students—to amplify the positive characteristics, talents, and abilities that define them. So as educators help students make a decision, the quality of the decision matters. It is not just a process of helping students make any decision, good or bad. It is trying to draw out the good (see Hansen, 2001). It is helping students learn how to make decisions that empower them to be more effective contributors to society. The addict makes decisions every day to remain addicted. An effective teacher is one who helps others make decisions that lead them away from harmful addictions, particularly the addiction to failure.

DETERMINATION

The process of leading others away from harmful behavior and toward a worthy goal demands determination. This is the third of the Three D’s. This is the hard work part of success. This occurs when a student cannot resist the pull to move toward that good goal. The student or teacher has progressed beyond “thinking about it” and “talking about it.” Now it’s time to do it, as shown in Figur...