![]()

Chapter 1

SAS FOUNDED

It would be wrong to start this book without providing the reader with a little background on the early history of the SAS. While so much has changed over the years, those original SAS soldiers were the first to adapt tactics and skills to suit their operational requirements. They learned from their mistakes, modified their tactics, and honed their skills. In this aspect little has changed over the years other than the great wealth of military knowledge that has been sharpened and refined. Hence, SAS tactics and operational skills started early in WWII.

By February 1941, British armored forces (known as Layforce) had crossed the Libyan Desert to a point south of Benghazi and cut off the retreating Italians. The resulting Battle of Beda, starting on February 5, inflicted heavy losses. Australian troops captured the major port of Benghazi on February 7, and two days later El Agheila was reached. There the advance stopped. Three days later, on February 12, the first units of the Africa Corps under Rommel arrived in Tripoli. The appearance of Rommel and his Corps in North Africa meant Layforce was split up into three units. One, under Laycock, fought in Crete, another was based around Tobruk, and the third unit (8 Commando) was sent to Syria where it took part in a number of raids on the Cyrenaica coastline.

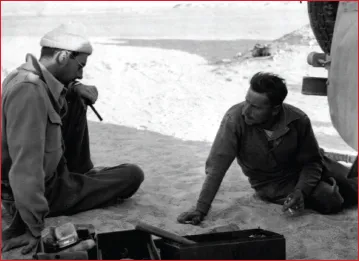

Colonel Sir Archibald David Stirling, founder of the Special Air Service.

One of the 8 Commando officers, a young Scots Guards Lieutenant by the name of David Stirling, had joined the Scots Guards supplementary reserve in 1938, but in the two years up to Dunkirk, he had spent much of his time traveling to North America, or when back in Britain sitting in his favorite chair at White’s Club. Many considered him to be a wastrel, an aristocrat who was easily bored. It was at White’s Club that Stirling had first heard of the Commandos and had promptly enlisted.

Stirling had been involved in a number of unsuccessful large-scale raids on enemy targets which were intended to bolster the defenses of Tobruk and to support the withdrawal from Crete. However, almost all of the commando raids were singularly unsuccessful, largely because they were too ambitious and unwieldy. In the end, Middle East Headquarters (MEHQ) decided that Layforce itself was to be disbanded as the men and materials were more urgently needed elsewhere.

Stirling in the meantime had visited his brother Peter in Cairo, who happened to be Third Secretary at the British Embassy (Stirling had three brothers, Peter, Hugh, and Bill). Stirling soon set himself up at his brother’s flat and proceeded to fall back into his old ways, with many a night spent partying or visiting the Scottish Hospital where he had befriended a local nurse. It was around this time that David Stirling met a young Lieutenant, Jock Lewes, in the Officers’ mess. Socially, the two men were as different as chalk and cheese, yet they soon discovered they shared a common belief. They were convinced the similarity lay in independent small-sized teams of specially trained men who could operate behind enemy lines. Lewes had been particularly impressed with the German parachute assault on the island of Crete, an assault which had cost the Germans dearly (German airborne forces suffered over seven thousand casualties), but had also won them a victory and with it, Crete. Just before Layforce was disbanded, Lewes had discovered some fifty parachutes, which had been landed at Port Said. These parachutes were awaiting destination for India. Lewes approached Laycock for permission to “borrow” a dozen or so and try them out—Laycock approved. Stirling, having heard of this, managed to get himself involved and preparations were made for a parachute jump.

Lieutenant John Steel Lewes ‘Jock’ originated the idea of Special Forces operating behind enemy lines which prompted Stirling’s vision of the SAS. Lewes is held by many as the co-founder of the SAS. Seen here on the right of the picture with David Stirling.

In June 1941, Jock Lewes and his batman, Roy Davies, made the first jump from an outdated Vickers Valentia biplane; both made it safely. Stirling and Mick D’Arcy jumped second, but Stirling’s parachute snagged on the tail section, ripping a large hole in the silk; consequently he had a hard landing. This landing paralyzed Stirling and also caused blindness for a short time, and thus he was sent to the hospital.

Most history books will tell you that it was here, lying in a hospital bed, that Stirling first conceived the idea of the SAS. This is not true. The truth is, Stirling had been bitten by the idea that he and Jock Lewes shared, and his time in the hospital allowed him to write down his thoughts into a proper proposal. Stirling also knew it would be futile to put his ideas through the normal chain of command—he was not popular with most of the junior General Staff officers. Luckily for Stirling, General Auchinleck had replaced General Wavell as Commander-in-Chief after the unsuccessful relief of Tobruk. Auchinleck was known for his like of devil-may-care soldiers; furthermore, he was a friend of the Stirling family.

Stirling understood the benefits of attacking targets behind enemy lines and disrupting Rommel’s supply lines, and better still of taking out his aircraft as the Luftwaffe had control of the skies at the time. He felt sure the raids would have a greater chance of success if executed by small groups of men, thus using the element of surprise to its best advantage. He also knew that a small unit of four or five men could operate more effectively, as they would all depend on each other and not on the overriding authority of rank. Raids would also be far more effective if they took place at night. All these ideas were refined and put to paper. The next step was to get his scheme endorsed.

It is stated that Stirling, despite his injuries, managed to gain access to MEHQ by climbing through a hole in the perimeter fence and reaching the office of General Richie, who at the time was Deputy Chief of Staff. Stirling presented his plan to Richie and the memorandum swiftly reached the desk of General Auchinleck. The idea suited Auchinleck’s purpose, for he was planning a new offensive later that same year.

Three days later, Stirling was ordered back to MEHQ. The meeting was brief but positive; Stirling was promoted to captain and given authority to recruit six officers and sixty other ranks. Brigadier Dudley Clarke, the man who had come up with the name “Commando” for Churchill, and at the time was running a deception unit at MEHQ, thus assigned Stirling’s new command as “L” Detachment, Special Air Service Brigade. This was a hopeful ruse that would fool the Germans into thinking the British had some form of elite troops in the area. And thus, the SAS was born.

David Stirling was determined to build a unit of dedicated men; men of ability and capable of self-discipline. He is quoted as saying, “We believe, as did the ancient Greeks who originated the word ‘Aristocracy,’ that every man with the right attitude and talents, regardless of birth and riches, has a capacity in his own lifetime of reaching that status in its true sense. In fact, in our SAS context, an individual soldier might prefer to go on serving as an NCO rather than leave the regiment in order to obtain an Officer’s commission. All ranks in the SAS are of ‘one company,’ in which a sense of class is both alien and ludicrous.” This ethos remains within the SAS family to the present day.

If David Stirling was the creator of the SAS, then Jock Lewes was its heart. In Stirling’s own words, “he was indispensable and I valued him more than I had ever originally appreciated.” David Stirling said of Lewes: “Jock could far more genuinely claim to be founder of the SAS than I.” If there is a reason why Jock Lewes did not receive full credit for his contribution to the forming of the SAS, it was his early death in December 1941, shortly after the SAS was first formed.

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne. All-around athlete and the one man who could get the job done. Mayne’s contribution to the SAS was exceptional.

The second man Stirling really wanted was Paddy Mayne. They had known each other during their service in Layforce where Mayne had undertaken one of the few successful operations. The nickname “Paddy” came with his Irish ancestry, and before the war he had been a solicitor and was well known for his accomplishments in the world of sport. In battle he possessed qualities of leadership which set him apart from most men, and a reputation built on his personal bravery, which at times was characterized as reckless and wild. Mayne was to prove that he would be the “fighter,” the man who would happily go into battle—and the man other men would happily follow into battle, to make the SAS a success.

When the SAS first arrived at Kabrit, the camp area designated to them, they were greeted by a small board stuck in the sand which read, L DETACHMENT SAS. Kabrit lay 90 miles east of Cairo on the edge of the Great Bitter Lake. There was nothing but sand. No buildings, no tents, no mess hall—nothing. Worse still the new “Brigade” had no weapons or supplies. As there was no parent unit, they had no one to call on for support. Stirling reported directly to General Auchinleck, and while this offered no support in the way of logistics, it was the first move in maintaining independence for the SAS.

The men of the unit begged, borrowed, or stole whatever they needed. Under cover of darkness they stole tents and equipment from the nearby New Zealanders’ camp, many of whom were away training in the desert at the time. They raided the Royal Engineers and stole cement and other building material. One of the best scroungers was a Londoner called Kaufman, who reportedly stole enough material from the RAF to construct a proper canteen. Kaufman raided and falsely requisitioned rations and stores which transformed the SAS camp into one of the best bases in the area. Kaufman soon realized that he was not cut out to be an SAS soldier, but he remained with the unit as a store man.

Lewes started the training based on what he expected the challenges to be like when operating deep behind enemy lines. Initially the men did a great deal of hiking through the desert carrying a full load of around 50lbs on their backs. During such hikes they were limited as to the amount of food and water they could carry. When in camp there was instruction on weapons, including British, German, and Italian. While hand grenades were available, it was found that they were not capable of destroying an aircraft with any consistency, and thus the “Lewes Bomb” was introduced.

Author’s Note: The bomb was designed by Lieutenant “Jock” Lewes, with the express purpose of destroying Second World War aircraft. The bomb was basic, a mixture of plastic explosive (TNT 808) thermite and a flammable fuel, normally diesel oil. This was attached to the aircraft where the wing met with the fuselage, and normally always on the right wing. A time pencil and a No. 27 detonator initiated the bomb. It was later found that the time-pencil was a glass tube with a spring loaded striker held in place by a copper wire. The top of the tube held a small glass vial of acid, which, when crushed, released the acid and burnt through the wire—the thicker the wire, the longer the delay. These proved very unreliable, and so other methods such as release and pressure switches were used. When completed, the whole bomb was put in a small sock-like bag and covered with a sticky compound so it would adhere to the aircraft.

The SAS also got busy with parachute training, which included jumping backwards off the back of a truck traveling at 30 mph. After several injuries, this method was abandoned and a proper jump training facility was to be designed and built by the nearby engineers. The first structure was a tower for parachute jumps and landing training.

However, despite the amount of ground training, parachuting and parachutes were relatively new and thus, many of the safety checks and procedures had yet to be realized and put into practice. On October 16, 1941, the first practice jump for the SAS took place. The first stick of ten men climbed into a Bristol Bombay aircraft of 216 Squadron which took off and settled at a height of around 900 feet. Several men jumped and landed without incident, but when Ken Warburton, a twenty-one-year-old, jumped, his parachute failed to open and he plummeted to his death. He was followed by Joe Duffy, Warburton’s best friend. Records show Duffy had suspicions that something was wrong and queried the jumpmaster sergeant. However, the humiliation of refusing to jump or RTU (Returned to Unit) overpowered his unease and he leapt. Again the parachute did not open and Duffy hit the ground, reportedly quite close to his friend.

Author’s Note: It has never been explained who invented the term Returned to Unit (RTU), probably Jock Lewes, but it appears that the discipline was in place from the very outset of the SAS. If a soldier either fails selection or is later expelled from the Regiment for misbehavior or a failing in standards, he is returned to his original unit. The term RTU can galvanize the SAS soldier to do things he would not normally do, even at the risk of personal injury. It is an ethos that exists to this day and applies to both officers and other ranks alike.

It was around this time that the famous insignia of the SAS materialized. There have been many a discussion on what the emblem depicts; some say it’s the flaming sword of Excalibur, while others claim it’s a winged dagger. It was Bob Tait who designed the cap badge, and the motto was down to David Stirling who, after listening to many an idea such as “Strike and Destroy,” came up with “Who Dares Wins.”

The famous SAS winged dagger.

By November 1941, L Detachment of the SAS was ready to carry out its first operation code-named Operation “Squatter.” The aim of a new offensive Auchinleck, code-named Operation “Crusader” was to retake Cyrenaica and secure the Libyan airfields which at the time were in enemy hands. If this could be achieved then shipping supplies to Malta could be increased; additionally it would open up Sicily for raids—the stepping stone to Italy.

On the night of November 16–17, a force of fifty-five men was divided into five aircraft provided by 216 Squadron and parachuted into the desert behind enemy lines. David Stirling, “Paddy” Mayne, Eoin McGonigal, “Jock” Lewes, and Lieutenant Bonnington commanded this force respectively. The raids would take place against the airfields in the area of Tmimi and Gazala. Rommel was also intending to advance and had plans of his own, as it was widely believed that the German Luftwaffe had received reinforcements in the form of the new Messerschmitt 109s. The parachute entry would drop the SAS twelve miles from the target. Once Operation Squatter was completed they would all rendezvous three miles southeast of the Gadd-el-Ahmar crossroads where the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) would be waiting to ferry them safely back to Kabrit.

The five Bristol Bombay aircraft took off on schedule. Although the night of take-off was clear and still, as the aircraft proceeded towards their drops zones, the weather quickly changed. Thick clouds, heavy rain, and high winds hampered navigation. In order to pinpoint their position, the aircraft were forced to drop down to 200 feet where they encountered heavy flak from the German defenses. The parachute drop was disastrous, with the men being scattered over a wide area on landing and several injuries being sustained—Stirling himself was knocked unconscious. In addition, all of the teams had been dropped way off target.

The operation was abandoned as a result. Individual soldiers made their own way to the rendezvous with the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). The problems encountered on this first operation prompted a radical rethinking about transporting troops to the target on future SAS missions. The main problem had been the weather. As fate would have it, the SAS had chosen to parachute in on a night when the weather was described as the worst in the region for thirty years. Notwithstanding, Stirling resolved never to use parachute drops again, preferring instead to use vehicles, starting with those of the LRDG.

Long Range Desert Group penetrated hundreds of miles in trucks and jeeps carrying repair facilities with them. They transported and collected the SAS after the first early raids.

The provisional war establishment of the LRDG was authorized in July 1940, originally for 11 officers and 76 men. This number was increased to 21 officers and 271 men in November 1940. By March 1942, the LRDG numbered 25 officers and 324 men. Operating in open-topped Chevrolet trucks, the LRDG carried out reconnaissance, intelligence gathering, a...