- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

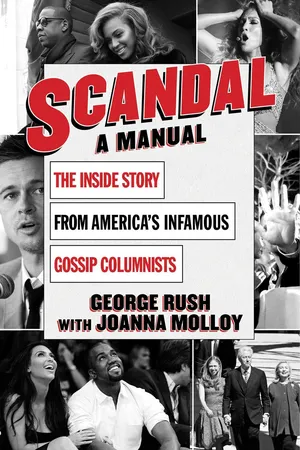

About this book

When the world first learned of Pam Anderson and Tommy Lee's impromptu wedding, when Sarah Jessica Parker had an explosive falling-out with her Sex and the City castmates, or when Ruth Madoff discovered the truth of Bernie's marital infidelity

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Nosey Parkers

If the bodies of George Rush and Joanna Molloy should ever be found floating in the East River, the lineup of suspects could rival any red carpet. Which celeb had finally gotten fed up with reading the swill those two wrote in the New York Daily News? Russell Crowe? Sean Penn? Robert De Niro? Perhaps even Police Commissioner Ray Kelly should be asked about his whereabouts on the night in question. But if we could speak from the morgue, we might advise detectives to check first for blood on the spiked heels of Sarah Jessica Parker.

We had a little history with SJP, to put it mildly. Years before it became a life-support system for fashionable women (and the gay men who love them), we witnessed the conception of her show, Sex and the City. In 1993, our pal, Candace Bushnell, started doing a column for the New York Observer. It was a thinly veiled diary of her life. Everybody knew that Mr. Big was Candace’s boyfriend, leather pants–wearing Vogue publisher Ron Galotti. Stanford Blatch was her manager Clifford Streit, who’d drop droll asides when we’d all be out at Nell’s or The Odeon or Bowery Bar. The following week, his bon mots would show up in Candace’s column. Clifford used to say, “I don’t mind if my friends use my lines, as long as they let me know in advance.”

Carrie Bradshaw, Sex and the City’s narrator, was, of course, Candace—only a tamer version of Candace. We never saw Carrie light up a joint in a restaurant while a police sergeant sat a few booths away. We never saw Carrie pee into a men’s urinal because she didn’t want to wait in line for the ladies’ room. Candace could drink Carrie under the table. But Candace also got up the next morning and wrote. Give her credit: she worked hard and almost single-handedly created modern chick lit.

Candace could be touchy. Once, we were checking out a tip about a guy her producer and friend, Darren Star, was dating. Candace was afraid the item would blow Darren’s deal to turn her “Sex and the City” columns into a TV show. We ran the item. Happily, HBO still green-lit Darren’s show.

Flash forward. Five years into the show, we kept hearing that all was not kissy-kissy on the Sex and the City set. After poking around for a few weeks, we ran a column headlined “‘Sex’ Without Love: A Four-way Feud?”

“They play the best of friends on HBO’s Sex and the City. But off-camera, we hear that relations among Sarah Jessica Parker and costars Kim Cattrall, Cynthia Nixon, and Kristin Davis have grown as chilly as those Cosmopolitans they’re always guzzling.‘When they sit down to shoot a scene in the coffee shop or a bar, they can barely look at each other,’ claims a source. ‘They never go anywhere together, unless they have to promote the show. They barely talk.’Several sources claim Parker is at the root of the frostiness.‘She makes about $3 million from the show—more than double what the others make,’ says a source. Though she now oversees the show as an executive producer, according to some, Parker is threatened by the popularity of Cattrall’s character, saucy bed-hopping Samantha.‘Sarah is jealous that Kim has got so big,’ says another source.”

We included several paragraphs of denials from spokespeople, who insisted there was no friction. Nevertheless, SJP did not let this assault go unanswered. She went to Liz Smith, who handed her entire Newsday column to the actress as a hankie:

“It was horrible to wake up after working twenty-hour days, as we all do, and have to read such nonsense,” Sarah [told Liz]. “Kim, Cynthia, Kristin, and I are all friends, personally and professionally, and I know we will go on being friends forever after. . . . I find the report has the old sexist overtone, about women cat-fighting. . . . Do James Gandolfini and Michael Imperioli fall in each other’s arms when they aren’t working on The Sopranos?”

When the column ran, the Daily News’s editor in chief, Ed Kosner, messaged us: “Given the vehemence of Sarah Jessica Parker’s blast in Liz today, are we comfortable with our sourcing?”

We had to go into Ed’s office. We told him we had four good sources who personally knew the cast members. In our next column, we ran a response to SJP’s response. We called her a “talented and hardworking actress.” We also observed that “the lady sounded as if she were protesting too much.” We noted that the Sopranos cast actually did hang out together after work.

Two years later, Parker still hadn’t forgotten. One night, HBO pulled out all the stops for a gala celebrating the final season of Sex and the City. The dinner was at the American Museum of Natural History in the Hall of Ocean Life, where a giant blue whale hung overhead. Parker was wearing fishnets, aquamarine pendant earrings, and a magenta dress that beautifully served up her cleavage. I spied her standing by a diorama of Polynesian pearl divers. Ignoring my instincts for self-preservation, I swam through the crowd and introduced myself.

“Mr. Rush,” she said sternly. “You’ve been very hard on me over the years.”

“Well not lately,” I said. “Correct me if I’m wrong, but . . .”

“You indicted my professional reputation,” she went on. “Let me tell you something, Mr. Rush. I love [my costars and crew]. . . . You should spend a few moments with me before you write something that’s not really based on anything but made-up allegations. . . . I’ve never lied about my personal life, my work, the way I’ve cared for three hundred people. Your article was one of the most painful things that ever happened to me. For thirty years I’ve been working and no one has said I’ve done anything bad.”

Every so often, I tried to slip in a word. Then she started getting personal.

“It’s a very peculiar job you have,” she said. “Why don’t you write longer pieces about people? You’re so much more dignified. You’re better than this, I’m certain. You must want better.”

I said, “We’re actually regarded as one of the more fair columns. . . .”

“My driver reads the Daily News every day,” she said (lest anyone mistake her for a subscriber to our working-class rag). “He couldn’t believe it. I care so deeply about my relationship with people I work with. You can ask a million people. I work harder than anybody. I work ninety hours a week. My reputation means the world to me. Always remember that! Because I couldn’t lie to you. I couldn’t face myself.”

It was a self-righteous rant that kind of corroborated the original story. But it had a touch of playfulness. After she got all that off her chest, she handed me an “olive branch.” It was invisible, but I ceremoniously put it in my pocket.

A few days later, Parker went on a radio show and talked about the caning she’d given me.

“I will say that he was really lovely about it,” she said. “He was dignified. He took it like a man. . . . And—who knows—perhaps we’ll be dining together one day. You never know.”

SJP gave Joanna a similar lecture one night when she covered a play Parker was in. “Why do you do what you do?” the actress had said, as though Joanna were an orphan she must rescue from the streets. Parker’s play dealt with the late, great fashion magazine, Flair. It was published in 1950, for just one year. Joanna sent a copy to her with a note telling her some of what we’re about to tell you here. SJP called and left a nice message, so maybe she “got it.”

SJP came to see more of us—probably more than she wanted. She and her husband, Matthew Broderick, enrolled their son, James, in the school where our son, Eamon, was a student. So we’d bump into them at drop-off. One morning, we were taking Eamon to school when we noticed that the New York Post had Parker’s picture on the front page. Our former assistant, Michael Riedel, who now wrote a much-feared column about Broadway, had reported that Sarah Jessica Parker hoped to star in a play about a husband-and-wife gossip-columnist team. The story said Broderick might play the husband.

After we dropped off our son, we ran into none other than Sarah Jessica Parker.

I said, “So we hear you and Matthew are playing us on Broadway?”

She looked baffled. We showed her the story in the Post.

“Well, it’s always nice to find out what I’m doing next,” she said.

She confirmed that she had done a reading with Alan Cumming of a play in progress by Douglas Carter Beane. He was calling it Mr. and Mrs. Fitch. She said nothing was set. But apparently the life of a gossip columnist had a “peculiar” appeal for her.

Working with your spouse is a good way to find out if you’re capable of homicide. Somehow, though, our marriage survived longer than those of many star couples we chronicled. In the course of writing almost four thousand columns, we watched America’s celebrity culture grow morbidly obese. Of course, we were partly to blame, having fattened readers with scoops about everybody from Lady Gaga to Moammar Khadafy. We’d walked into the paper’s art deco building on Forty-Second Street in time to catch the last whiff of its Sweet Smell of Success newsroom. As the news cycle spun faster and faster, the job invaded our home to the point where our five-year-old son was suggesting blind items. We wrote our last item in a blogosphere shrill with tweets from Jersey Shore. Along the way, we turned down some bribes, made some impressive enemies, and became unlikely relationship counselors to star-crossed lovers. We also came away with a few tales that we’ve kept to ourselves—until now.

What follows is a collection of case studies—a personal handbook that illustrates how reputations are smeared and scrubbed clean. It demonstrates how scandals are started and how they can be, if not stopped, slowed down. Our education in infamy may provide a little guidance in how the famous will ignore you, bully you, bludgeon you, and, occasionally, try to seduce you. This is a cautionary tale for any reporter who might face off with slippery public figures who possess money, fame, and power. Those who protect such public figures may see it as a manual for taking advantage of reporters. Readers who don’t fall into either category may just enjoy watching the fight—and learning a few things that your favorite stars would rather you not find out.

2

No Experience Necessary

Neither of us set out to write a celebrity column. And yet, we can see now how our families planted the seeds—and, dare we say, spread the fertilizer—for our future crops of gossip.

As Joanna tells it:

My family didn’t have a lot of money. But the stories they told about New York were like gold to me. Most of them had lived in Manhattan since the 1840s, since fleeing the Great Famine in Ireland. They had names like Baby Rosaleen, Chickie, Patsy, and Zahbelle. During Prohibition, my grandfather, Ray Molloy, saw some gangsters riddle “Mad Dog” Coll with Tommy gun bullets while he made a phone call at London Chemists in Chelsea.

One of my aunts would note, “Yeah, it was the last straw for Dutch Schultz and Owney Madden when Mad Dog kidnapped Frenchy.”

That would be Big Frenchy DeMange, Madden’s estranged partner in Harlem’s Cotton Club. Mad Dog had kept French hostage in the Cornish Arms Hotel on West Twenty-Third across the street from our family business, the Molloy Funeral Home.

“You know, they say Mad Dog sent Frenchy’s private parts to his mother in a box,” said one of my aunts.

Another aunt yelled, “How did she know they were his?!”

Laughter and much clinking of ice in glasses filled the room. I was about twelve and glad they hadn’t banished me from the room.

One of my cousins, Georgie Rooney, was a cop who walked the beat in Hell’s Kitchen. One day a teenager threw a rock that knocked his cap off. The kid’s name was Mickey Featherstone. He was a repeat offender. Cousin Georgie saw him again a couple of weeks later, sitting as calm as clams on a milkbox at a gas station. Georgie asked him, “Which hand did you throw the rock with?” With a smirk, he held out his right hand. Georgie grabbed it and crushed his fingers against the curb, breaking some. “He didn’t even flinch,” Georgie said. “He showed no feeling of pain whatsoever.” Featherstone grew up to be a famous killer for the Westies gang.

When I walk around New York, I see the ghosts of my older relatives. There’s the horse market outside the Flatiron Building where a white stallion broke free and ran down Twenty-Third Street. There’s the wooden stand at Thirty-Fourth and Broadway, where a cop held up colored lanterns before there were traffic lights. Out in Rockaway and Gerritson Beach, there are the bungalows they built when you could rent a stretch of sand from the city for two dollars.

I still hear their songs and their expressions. They’d say our ancestor, John Hennessey, a cabinetmaker on Thames Street “came home in tatters” from the Civil War. They recalled neighborhood characters who’d purposely get arrested for vagrancy come wintertime, so they could get “three hots and a cot” in jail. Girls were warned, “Whenever a girl whistles, the Virgin Mary cries.” Brides were given my great-great grandmother’s mystifying birth-control advice: “Make tea in the kitchen, but spit in the parlor.” In the era of spittoons, that must have been her way of explaining the rhythm method.

It didn’t work too well, since her daughter, Auntie Lala, had eight kids. One summer, one of her twins, Irene, was swimming in a lake and drowned. Lala was heartbroken, but then she became pregnant again—with another pair of twins. She was overjoyed to deliver Josephine and Juliette. She was pushing them in a pram near Madison Square Park one day when there was some kind of explosion in the street. Juliette died in the pram. Lala’s sister, Juliette, after whom the baby had been named, asked if the family could pretend that it was Josephine who’d died. That way, Juliette would still have a living namesake. Lala, beset with grief, agreed to rename Josephine “Juliette.” The pathos of this story compelled my family to keep telling it nearly one hundred years later. And that’s where I got the sense that telling true stories was an important thing to do.

My parents and their four children lived for a time in the Bronx, on Blackrock Avenue, near Castle Hill Avenue, about eight blocks from the projects where Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor grew up. Singer Jennifer Lopez later lived two blocks down Blackrock and went to our school, Holy Family. My father bought all the papers. He made sure I followed columnist Pete Hamill, who helped wrestle the gun away from Sirhan Sirhan when he shot Bobby Kennedy. But I would also read the “Suzy Says” society column in the Daily News. “Suzy,” the pen name of Aileen Mehle, allowed me to escape from the Bronx into a fantasy world. She wrote about the ladies who lunched and the film stars I’d see on the three TV channels that all showed classic movies every day at 4 o’clock—the same ones Meryl Streep has said inspired her to become an actress. Don’t get me wrong; our street games were fun. But it was a tonic to dream about Mrs. Muffie McFancyton dancing at galas with her silk Yves St. Laurent evening gowns and her jewels. Little did I know that the designers and party planners and hotels and florists all had press agents who pushed Suzy to plug their clients. No matter. I pictured the Astors and the Vanderbilts and th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- 1. Nosey Parkers

- 2. No Experience Necessary

- 3. "Tart it up a bit."

- 4. Post Script

- 5. "Have You Two Met?"

- 6. Meet You On Forty-Second Street

- 7. Our New Mattress

- 8. Westward Ho!

- 9. Frienemies

- 10. Pleas For Mercy

- 11. Clashes With The Titans

- 12. The Spin Doctor Is In

- 13. Media Relations

- 14. Camelot on the Hudson

- 15. Diddy, Clef, And Hova

- 16. Bubbalicous

- 17. The End Of Gossip

- 18. Bushwackers

- 19. In Bed With the Flesh Peddlers

- 20. Old Grudges and Fresh Feuds

- 21. Reacquaintances

- 22. The Threadbare Red Carpet

- 23. A Change Of Pace

- 24. Rush & Molloy Split

- 25. People Will Talk

- acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Scandal by George Rush in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.