eBook - ePub

On Women's Films

Across Worlds and Generations

This is a test

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On Women's Films

Across Worlds and Generations

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

On Women's Films looks at contemporary and classic films from emerging and established makers such as Maria Augusta Ramos, Xiaolu Guo, Valérie Massadian, Lynne Ramsay, Lucrecia Martel, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, Chantal Akerman, or Claire Denis. The collection is also tuned to the continued provocation of feminist cinema landmarks such as Chick Strand's Soft Fiction; Barbara Loden's Wanda; Valie Export's Invisible Adversaries, Cecilia Mangini's Essere donne. Attentive to minor moments, to the pauses and the charge and forms bodies adopt through cinema, the contributors suggest the capacity of women's films to embrace, shape and question the world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access On Women's Films by Ivone Margulies, Jeremi Szaniawski, Ivone Margulies,Jeremi Szaniawski, Ivone Margulies, Jeremi Szaniawski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Phrasing (in)Significance

1

Wanda’s Slowness

Enduring Insignificance

Elena Gorfinkel

I like slow paced films. You’ll notice Wanda is a very slow paced picture. It was played more or less as an art film, not a commercial film. Not everyone is going to like it.

Barbara Loden, 19741

Wanda does not stand for mothers, or for modern women, or for victims. There is no representation. Wanda always comes up absent.

Dirk Lauwaert2

No film more animates a feminist film imaginary than Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970). It is a film about a working-class woman from mining country who abandons her given vocation as wife and mother, and proceeds to drift, eventually fastening herself to a small-time thief, Mr. Dennis, a petty tyrant and malcontent who harnesses the shiftless Wanda for his own purposes. Seeking bare attachment, the most rudimentary of human needs, she gets enlisted in his script, bidden to act in his drama—to stick up a bank. For the two transient loners, the heist ends badly. Wanda drifts onward.

Loden’s film sits at an uneasy angle to the discourses of women’s liberation of its time as well as to the demand for “positive” representations that would emerge in early 1970s feminist film criticism. Neither affirmative nor bound to psychological interiority, Wanda drew on an aesthetic palette associated as much with the French New Wave, cinema vérité, and the independent cinemas of Shirley Clarke and John Cassavetes, as with the energies and formal strategies of underground films—as Loden had expressed a concerted affinity with more experimental work, its “take a camera and film it” ethos (in Thomas 1971, G17). It also seems to advance some of the motifs of dispossession in many of the drifter, road films of the late 1960s and 1970s—The Rain People (1969), Five Easy Pieces (1970), Boxcar Bertha (1972), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)—but differs considerably from them in its mercurial style and in its unremitting pessimism.

Loden’s aesthetic is distinct, set apart from these movements and developments, perhaps due to some combination of her marginality to the industry and her economic independence. The singular historicity of Wanda, as the fledgling film of an actor-director-screenwriter, its rough-hewn style and spare precision seem to both instantiate and reinforce the film as a palimpsest of failures, textual and extratextual (despite the film’s resounding critical successes). Loden’s prescience rests in focalizing pressing considerations of labor, gender, and survival, made in advance of two key films of women’s refusal and drift: Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985). The gestural specificity of Loden’s performance, her habitation within the exhausted lifetime of rural Appalachia, its aesthetics of passivity and failure, resonate deeply with tendencies afoot in contemporary cinemas of duration and observation.

The acute figuration of refusal in obstinacy and passivity that Loden’s Wanda calls forth has remained a difficult kernel for feminist criticism and film theory to digest, especially a critical project rooted in affirmative representations, positive images, and a politics of the cinematic apparatus that aims to eradicate social inequalities. Lauren Rabinowitz talks of the radical uprisings of the era of the “long 1968” in which revolution came in the “public demonstration of a refusal,” and in the revelation of the dependency of image culture on female bodies and the dirty realities of women’s work and care labor, “bringing into view the vomiting pregnant woman, the sink full of dirty dishes, the shitty diapers, as much as it meant revealing women’s erotic desires” (2001, 95). Wanda, in contrast, untimely and before its time, channels other strategies of image making and performance, ones bound up in affective presence, in the temporality and phenomenology of granular performance, and in an aesthetic less demonstrative than radically descriptive, in the burning cut of exposure.

Critically praised on its release, winning the International Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1970, and subsequently screened at Cannes, Wanda was largely forgotten for two decades. It became a curio in the history of women’s filmmaking, infrequently associated with the masculinist developments of New Hollywood. Despite efforts to make another feature-length film, it remained Loden’s only major work before her premature death from breast cancer in 1980 at age forty-eight.3

This narrative has made Wanda a lodestone, a testimony to the challenges of women’s film practice in the US film industry.4 Such recent feminist and cinephile recuperations of Loden have relied on the frangible historicity of the filmmaker as the manifestation of Wanda the character, and Wanda the minor-yet-major filmic work. The film is thus imbued with a time-shifting, mournful, reflexive sense of historicity, which has become part of its textual and extratextual meanings, inscribed in its scenes of reception. Acolytes, critics, and scholars have taken on their own processes of “Looking for Barbara Loden.”5 Feminist cinephiles seek the filmmaker Barbara Loden in the ephemera of her existence, in the traces of her image, charting signs of the Wanda to come in the Loden before Wanda, of the traces and divining predisposition toward that gesture, described by Nathalie Léger’s in her Suite for Barbara Loden (2012), to tell the story of “a woman telling her own story through that of another woman” (6).

Loden created the character Wanda from a relayed transcription and reimagining of another woman’s story. Loden read a newspaper article about Alma Malone, collaborator with a male partner in a bank robbery, who when sentenced to twenty years in prison, thanked the judge.6 Loden described her encounter with the story and the beginning of the script for Wanda, “I was fascinated by what kind of girl would be that passive and numb, so I developed that character” (in Reed 1971, 52). Wanda Goronski, written into existence in the early 1960s and emerging on 16mm film in 1970, rose from this composite of realities and imaginings. The ineluctable expression of gratitude for an impending imprisonment, a willful submission to unfreedom and a punitive law, oriented Loden’s fascination and provides a tantalizing key to the film, of assent and acquiescence writ large.

Loden before Wanda

Barbara Loden’s life story has mesmerized critics and scholars. It is a familiar narrative of overcoming and failure, a contest between a woman’s self-determination and her overdetermination as woman, performer, mistress, wife, mother, blonde, ingénue. Moving to New York City from North Carolina at age sixteen with $100 to her name, Loden in the 1950s worked variously posing for pinups, modeling for story magazines, and dancing. While performing at the Copacabana, she met her first husband Larry Joachim. She was soon “discovered” by television impresario Ernie Kovacs who cast her in The Ernie Kovacs Show as his sidekick in his broadcast experiments. Loden’s body served as a medium for Kovacs, her material presence the substrate of his special effects. In one bit, Kovacs sawed her in half; in another, he performed a novel effects trick in which he was visible literally seeing through Loden’s body, his eye telescoping through her forehead. These minor moments of Barbara Loden as subject and as object, her body as a medium and pliable material, instrument, and prop, seem less incidental when seen through the larger arc of her whole career, an agon with acting as instrumentality. While recollecting her early career, Loden confessed, “I never wanted to be an actress, I thought they were phony,” yet “what got me started in acting lessons was a need to get over being withdrawn and inhibited.” She also wanted to lose her Southern accent, thus taking many voice lessons (Reed 1971, 52).

Loden, while taking acting classes with Method teacher Paul Mann, began to appear in small Broadway and Off-Broadway productions, to some small recognition. Her first and primary film roles were as a supporting player. She was cast by Elia Kazan, whom she first met in 1957, as a distinct personality, a Southern secretary in Wild River (1960). Even more notable was her role as the tempestuous flapper Ginny Stamper in Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass (1961). Perhaps most constitutive, however, of her as persona, personality, and actor was Loden’s biographical framing as Elia Kazan’s partner, first as his mistress and then eventual wife. Berenice Reynaud chronicles (2002, 226) Loden’s appearance in Kazan’s autobiography (in the absence of other sources), tracing how the actress long lived in the outsized shadow of “Hollywood’s sacred monster.” Loden won a Tony award for her role as Maggie under Kazan’s direction in the play After the Fall in 1964. The script by playwright Arthur Miller was based on his relationship with the tragic bombshell Marilyn Monroe.

As Reynaud notes, Loden was frequently not chosen for various projects, including Kazan’s film adaptation of his novel based on their relationship, The Arrangement (1967, novel/1969, film). That role went to Faye Dunaway, who had acted as Loden’s understudy in After the Fall, fresh from her success in Bonnie & Clyde (1968). For The Swimmer (1968), she was cast as Burt Lancaster’s mistress. A series of disputes led to a change in directors; Loden was excised from the film. Yet, interviews and accounts from the time also reveal Loden’s stated ambivalence toward acting and Hollywood as an industry more broadly, and her habit of declining offers for many roles.

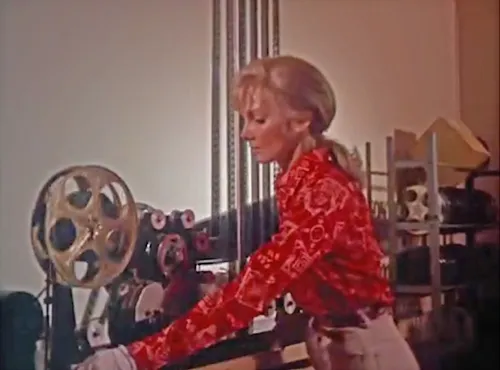

Yet another failed project was Loden’s presence as the romantic lead in the shelved Alan Smithee film Fade In (1968), released as a TV movie in 1973. As if a foreshadowing, Loden starred as a Hollywood film editor, working on a Western film set in Moab, Utah (Fig. 1.1). She unexpectedly falls in love with a rancher, a young Burt Reynolds. On a date, the rancher asks her what she does. Loden’s character cheekily replies, “Can’t you tell? I’m an actress, I play tortured women who have been terribly hurt so they drink to forget.” The film ends with Loden’s character leaving Utah, choosing not to pursue her city-country affair, her career too important. A refusal of romance, but nevertheless an inscription of refusal—however faint, yet still in a fiction not her own.

FIGURE 1.1 Loden in the shelved Fade In (Paramount Pictures, 1968).

Fatigue archive

On movie memorabilia auction sites, I search for Barbara Loden in press materials, and come upon undated photographic stills. A guess might place them in the late 1950s. The back of each photograph is inscribed, “Barbara Loden, Broadway actress/model.” It is unclear if they are non-professionally produced, but clearly, they were used promotionally in the period when she was studying Method acting. A young Loden, hair short and boyish, is posing in a derelict attic, “bones” bare, drywall exposed. In one, Loden is standing on a stepstool, acting out (or sincerely enacting), reaching for a ceiling beam with a piece of wood. Whose house, whose attic is this, what is the status of her performed labor, and what character is Loden prospectively playing in it? In another, she holds a drawer from a disassembled dresser that sits at her feet. A boiler and pipes snake around her, raw stone walls, as she stands effortful amid junk, arrested in the process of wearying labor—a handkerchief peeks out of her back pocket. She is cast in a role that seems off script, a seeming vagabond, neither ingénue nor seductress, outside of a recognizable zone of reproductive labor or spectacular performance.

FIGURE 1.2 Loden promotional photograph (undated & uncredited, circa 1950s. Rights holder ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: On Women’s Films: Moving Thought Across Worlds and Generations

- Part One Phrasing (in)Significance

- Part Two Collective Voice and Documentary Poetics

- Part Three Embodied Configurations: Material and Self-inscription

- Part Four Subjectivities Across Local, National, and Neoliberal Logics

- Part Five Women’s Imaginaries, Same-sex Worlds

- Notes on Contributors

- Index of Names and Titles

- Copyright