![]()

1 The history of the Vrina Plain

Simon Greenslade

Location

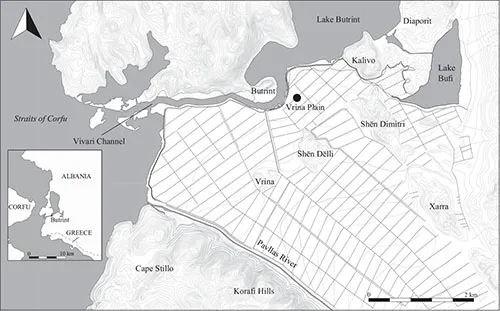

The Vrina Plain lies to the south of the city of Butrint (Fig. 1.1). Bordered to the southwest by the Korafi hills and stretching to the southeast as far as the conical hill of Cuka e Ajtoit, close to the Greek border, this alluvial valley covers an area of approximately 20 km². Dotted across this seemingly flat plateau are a number of limestone outcrops upon which the modern-day settlements of Shën Dëlli, Xarra and Vrina are located. A further outcrop is that of Kalivo, bordering the southern margin of Lake Butrint (Fig. 1.2).

The Plain is separated from Butrint by the Vivari Channel which links Lake Butrint to the Straits of Corfu. This saltwater channel was originally the mouth of the River Bistrica, which ran into the north end of Lake Butrint.

Central to the plain is Lake Butrint, which covers an area of 1600 hectares. The quality of the water in the lake can be divided into two distinct layers. The upper layer (approximately 8 m in depth) is rich in oxygen and supports a diverse marine culture. The salinity of this layer changes seasonally from winter to summer. The lower layer (approximately 14 m in depth) lacks oxygen and is sulphurous. The lake is rich in fish species including mullet, eel, bream, wrasse, sardine and anchovies. Mussels are the predominant mollusc and have been farmed in the lake since 1968. The north and south shores of the lake today are flanked by saltwater marshes with associated amphibian, reptile and bird populations.

To the southeast of Lake Butrint is the much smaller Lake Bufi. This covers an area of 83 hectares and has an average depth of 1 m. Fed by freshwater springs, it originally drained into Lake Butrint but is now connected by a cut channel that allows water to flow either way between the lakes. As a result, saline water from Lake Butrint has increased the salinity of Lake Bufi.

The pastoral aspect of the low-lying area visible today is largely a result of the implementation of a state-run collective agricultural policy by the communist government of the 1960s and 1970s, based on a model developed by the Chinese, their ideological allies at the time. With the institution of state farms at the villages of Xarra and Vrina, woodland which had covered much of the plain was removed and a grid of large irrigation channels was dug across the plain in order to drain the marshy area, thereby creating a usable space for crops and animal grazing.

The formation of the Vrina Plain

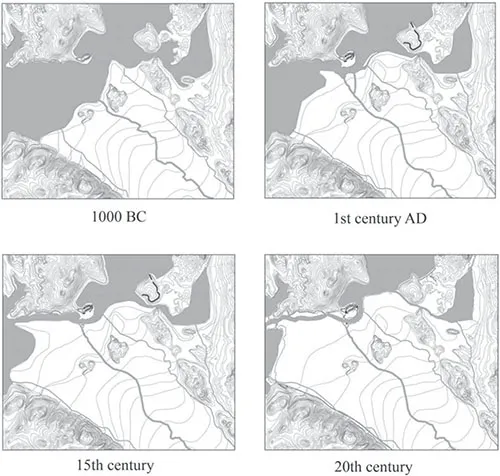

Like many coastal locations within the Mediterranean Basin, the Vrina Plain is a dynamic and continually evolving landscape, created by a complex interaction of natural and human processes over the last 15,000 years. Changes in sea level and the climate as well as tectonic movements have all had a pronounced effect on the plain’s evolution (Fig. 1.3). Even today the scale of this can be seen with regard to the modern coastline which is now over 2 km west of the once-fabled port city of Butrint, with seaward access via the Vivari Channel.

Sedimentary analysis of core samples taken across the area would seem to indicate that the entire plain, together with Lake Butrint and Lake Bufi, once formed part of a large coastal bay of the Ionian Sea stretching potentially as far as Phoenice to the north and Mursia to the southeast. From around 5200 BP the bay appears to have begun to silt up with alluvial material brought down by the Pavllas and Bistrica rivers, the two main rivers of the area. This created a mixture of marsh and wetland habitats interspersed with small islands separated by narrow channels. These changes seem to have been accelerated by changes to the environment connected with the opening up of the Holocene vegetation, beginning about 6600 BP and becoming much more pronounced after about 4000 BP.

By 2700 BP the sediment input appears to have increased and the development of the plain was dominated by the growth of large deltas to the seaward side of Butrint, resulting in the formation of a stable alluvial floodplain with well-drained soils suitable for agrarian settlement. There are likely to have existed at least two major channels running along the axis of the valley, depositing sediment into the bay from an extensive inland catchment. Smaller channels relating to more local catchments would also have formed, one draining the now lagoonal Lake Bufi, and another, located to the east of present day settlement of Shën Dëlli, draining from the high ground east of Xarra. These would have contributed to marshy deltaic formations extending northeastwards towards the city of Butrint. By this stage the original bay was separated from the coast by a narrow channel, which may have had important consequences for the operation of a port at Butrint.

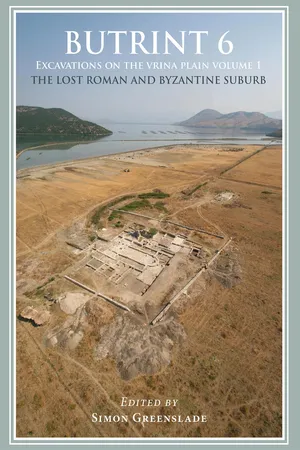

Figure 1.1. The Vrina Plain looking south from the acropolis of Butrint city

With the water table dropping, land on the south side of the channel became elevated above the waterline, and except after thunderstorms or prolonged winter rain, must have been exposed and covered in vegetation. From the middle of the 1st century AD, continued silting resulted in a number of topographical high points with sufficiently well-drained alluvial soils to allow for the expansion of a suburban settlement beyond the confines of the earlier city. Channels, by now much reduced in size, are likely to have been relatively stable, with a sediment load dominated by fine silts forming cohesive banks fixed with vegetation. Strabo (VII.324.446), the lst-century geographer, associates Butrint’s harbour with Pelodes Limen or muddy harbour. Whether he had actually visited the town is doubtful; more probably he had heard from merchants or travellers who recalled disdainfully the murky waters in the Vivari Channel. Even today heavy storms wash down soil from the surrounding hills which darkens not only the rivers but also Lake Butrint, leaving great muddy fans exuding from the mouths of the channels into the Straits of Corfu, a situation Gerald Durrell clearly describes in My Family and Other Animals.

Throughout this time the Vrina Plain was constantly evolving. The establishment of the Roman colony is likely to have brought about extensive regional landscape modifications. Centuriation along the valley would have been an integral part of the colonial landscape remodelling and drainage schemes may also have been implemented. Sedimentary deposition continued during the Roman period as catchment modifications, including channel straightening, deforestation and urbanisation, will have affected the rivers’ sediment loads and increased the potential for flooding. Field investigations upon the plain have identified Roman Republican layers buried beneath up to 1.20 m of alluvium. Archaeometric evidence suggests that channel silting increased around AD 450–500, possibly linked to changes in Roman agricultural practice and associated sea-level rises. This in turn led to the submergence of the Roman levels.

The changes continued into the medieval period, with renewed inundation of former wetlands possibly increasing the size of the large delta around the mouth of the sea inlet. This may relate to the medieval revival of Butrint and the renewed utilization of the alluvial plain, especially along the levee banks of the main channels flowing down the valley, offering well-drained fertile soils.

Figure 1.2. Location map showing the Vrina Plain

Figure 1.3. The development of the Vrina Plain

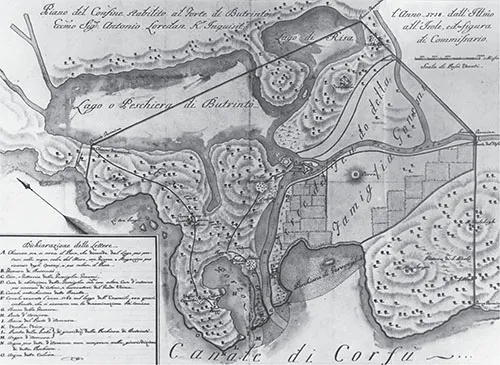

Figure 1.4. Cadastral Map of 1718 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome)

It would appear that by the 18th century the plain had predominately reverted to a wetland marsh environment, which may reflect a relative rise in sea level, again as a result of subsidence in the area.

The earliest detailed map of the Vrina Plain, a 1718 Venetian Cadastral map, records it as an area of low hills with beyond it, towards Kalivo, paludo – marshland (Fig. 1.4). In 1818 the British, Austrian and Neapolitan governments undertook a combined venture to survey the Albanian coastline under the command of Capt. W. H. Smyth. Published in 1825, Smyth’s map for the Admiralty, Chart of the Channels of Corfu with the Adjacent Coast of Albania, clearly depicts the Vrina Plain as having the same topography as that of the 1718 map. In the following year, the Carte physique historique de la Grèce by the French Lt. General Comte Guilleminoit was published with an inset map of Butrint. The French never undertook a comprehensive survey of southern Albania but based the map partially on the observations of French Grand Tourists who had visited the site and partly on military data collected during the short-lived French occupation of the Ionian islands in the late 18th century. Again the map depicts the area directly opposite the city of Butrint as a marsh.

Smyth’s charts were updated in 1840 when Butrint Bay was fully sounded, and again in 1863 when Commander A. L. Mansell and HMS Firefly undertook an extensive new survey of the area, despatching surveying parties inland to create the first true topographic survey of Butrint and its immediate environs. On this survey, published ...