![]()

Part One

Weeding Out the Bad Element

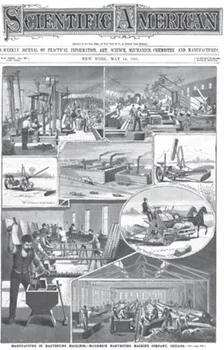

This 1881 illustration depicts McCormick Works, the products produced there, and workers in some of the plant’s many departments, including the machine shop (upper left) and the foundry (bottom right). [Scientific American, internet archive, scientific-american-1881-05-14]

Cyrus McCormick II, eldest son of the “Reaper King,” in 1880, when he was twenty years old. Cyrus II became president of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in 1884 and then served for several decades as the head of International Harvester after its founding in 1902. [Chicago History Museum, IHCI-31326]

A clash on May 3, 1886, between workers and police outside McCormick Works left several workers dead and triggered the protest rally at McCormick Works the following evening. [Chicago History Museum, IHCi-03659]

The famous “REVENGE ”circular, written by Chicago anarchist and labor leader August Spies (though someone else added on the “REVENGE” header) following the confrontation “at McCormicks.” [University of Illinois Digital Collection]

August Spies, thirty years old, after his arrest in 1886 for his part in the Haymarket “riot.” He was executed the following year. [Chicago History Museum IHCi-30017]

Harold McCormick, Cyrus II’s younger brother, and his first wife Edith Rockefeller, in 1895. This matrimonial merger proved critical to the formation of International Harvester and the McCormick family’s ability to maintain control over the corporation. [Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-8374]

A 1915 scene inside McCormick Works, now part of the International Harvester empire. Note the foreman on the extreme right. [Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-7958]

Few women were ever employed in McCormick Works, but many were in the adjacent Twine Mill, where some aspects of the production of binder twine were deemed “women’s work.” This photo is from 1912. [Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-9108]

In 1928, workers pour out of McCormick Works as their shift ends. At its height nearly eight thousand people were employed at the plant. [Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-9370]

![]()

1.

The Reaper Kingdom

It was the sunlit springtime of 1879 at Princeton College and the magnolias were in bloom, but as Cyrus McCormick II traversed the campus he was absorbed by thoughts of his hazy and foul-smelling hometown. He had just received a letter from William Hanna, a devoted member of the office staff of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago. The senior Cyrus, widely known as “the Reaper King,” still presided over the manufacturing concern he’d founded, but he was more than seventy years old and by this point exercised no oversight over its day-to-day operations. The factory, Hanna warned in his letter, “practically has no head”; employees “are allowed far too much freedom, and feel quite independent.” Hanna urged the industrial heir to interrupt his studies and return to the family firm. “The place is ripe for you,” Hanna wrote. “I rejoice that this business … is about to take new life and fresh impetus in the person of one who bears the full name and character of him who founded it so long ago.”1

Cyrus McCormick II was just nineteen years old. He was darkly handsome, tall and strapping, and very, very rich. Many young men in those circumstances would prefer to dally longer in college—graduation was a few months away—and then engage in some serious carousing before shouldering adult burdens. Young Cyrus was clearly daunted by just how much he was being asked to do. “It was, I confess,” he later reflected, “a somewhat staggering responsibility, for our business practically covered the world. We were at home in every wheat field on the globe. We had agencies in many lands and had to keep in touch with agricultural, business, and financial conditions all over.” This was a role, though, he had been groomed for since birth. His parents, both ardent Old School Presbyterians—as befit the McCormicks’ Scotch-Irish heritage—resolved to instill in their children the cardinal Calvinist principles of self-discipline, duty, and toil. Cyrus and his siblings were required to note how long they spent getting dressed and brushing their teeth, so they might become more efficient stewards of their time and not keep others waiting at the breakfast table. But as the oldest, Cyrus II was singled out for particular attention, and by his early teens he was already immersed in the family enterprise. “My father taught me that I must work, and must work out my own salvation,” Cyrus said; in practical terms this meant “that I must apply my whole energy to learning every phase of the business.”2

The business he was called on to understand did not simply manufacture products: it also made history. Cyrus McCormick I’s mechanical reaper, introduced in 1831, substituted horse for human power and cut and threshed grain in one efficient process; by effecting an exponential increase in agricultural output it made modern farming, not to mention the growth of the United States, possible.3 Determining that the vast territory out west was where his reaper’s potential would be best realized, McCormick left his native Virginia in 1847 and headed for a frontier outpost with no sewers or paved streets, where livestock still ambled freely through town: Chicago.4 He set up shop in a building smack in the heart of the city, on the north branch of the Chicago River. Within a year he’d sold eight hundred reapers; by 1860 he’d built a new three-story brick factory—said to be the largest in the world—where some 250 workers turned out more than four thousand machines annually. Chicago by this point was an emergent industrial powerhouse and had become the fourth-largest metropolis in the United States. “Tool maker, stacker of wheat,” so Carl Sandburg would one day define the city, and McCormick’s company involved both, producing the implements that transformed the Great Plains into the nation’s breadbasket and fixed Chicago at the center of the commodification of grain.

Cyrus McCormick also expanded his enterprise through his aggressive business acumen, introducing practices that later became commonplace, like fixed prices, installment payments, traveling sales agents, and widespread advertising. He outmaneuvered, out-innovated, or bought out his competitors and energetically marketed his brand overseas; by the 1870s McCormick reapers were in use as far away as Russia and New Zealand. McCormick also built a giant portfolio, diversifying his wealth and investing heavily in property, which included the family mansion, an ersatz Louvre that sprawled over a full city block. He became Chicago’s biggest landlord and one of nineteenth-century America’s few multimillionaires.5

With all his energy directed toward his business, Cyrus I was nearly fifty when he married twenty-three-year-old Nettie Fowler. It was in all respects a fruitful partnership. From the outset Nettie evidenced a keen business sense and an iron will, and she was utterly determined that her eldest son would take his rightful place within the family enterprise. Indeed, she ensured that the business survived so that he might inherit it. When the great fire of 1871 decimated Chicago, sixty-two-year-old Cyrus I inspected the smoldering ruin that had been his sole manufacturing establishment and considered calling it quits. Nettie would have none of that. “Rebuild at once,” she insisted. “She had in mind,” one biographer said, “the future of another Cyrus H. McCormick, by this time twelve years of age.”6 So Cyrus I bought a far bigger parcel of land, this time on the city’s Southwest Side, and constructed a colossal plant capable of producing fifteen thousand reapers a year.

From an early age Cyrus McCormick II demonstrated the character traits his parents had hoped to instill in him. Intense and serious, he was devoted to his mother and idolized his father, at no point evidencing even a trace of rebelliousness. When Cyrus II was a teenager, it appeared possible that he might be dispatched to Paris on company business by himself, a prospect that horrified Nettie: she envisioned her boy “like a lamb among wolves [in] that most dangerous and gilded pathway to destruction!” Father and son ultimately went to France together—but young Cyrus reassured his mother nonetheless. “Please don’t worry about me,” he said. “I shall always be conservative.”7

Thus, when William Hanna’s anxious entreaty reached Princeton, young Cyrus never considered refusing it. He was no reluctant prince. He missed the graduation festivities (but was recognized as a member of the Princeton class of 1879 nonetheless) and hastened back to Chicago. It had fallen to nineteen-year-old Cyrus II to rescue the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company and perpetuate his father’s legacy.8

Young Cyrus would now be spending most of his time at the factory commonly called the McCormick Works. To get there from the family’s North Side estate, he would point his carriage toward the intersection of Blue Island and Western avenues, heading far past Chicago’s downtown bustle, out to where the streets faded into farmland. His destination was impossible to miss: he would see first, from some distance away, the towering smokestacks and their inky plumes that draped a perpetual shroud of soot over everything in the vicinity. And then the Works itself would come into view, ascending multiple stories and spreading out over acres of prairie grass. There was nothing else of any size anywhere near it. Jutting abruptly up from a flat plain, it looked a bit like an industrial Versailles, albeit one composed of red brick and devoid of decorative detail. And rather than tranquil gardens, the factory was surrounded by a noisy tangle of transportation: a constant flow of carts and wagons, railroad tracks that fed trains directly into the plant’s warehouses, schooners on the adjacent branch of the Chicago River bringing in raw materials from distant ports.

Once through the iron gates and into McCormick Works the din did not subside. In the twenty-acre factory yard, teams of draft horses and mules—the company maintained a stable full of them—snorted as they strained against the weight of freight cars loaded down with supplies and finished goods. By this point the works was producing reapers, mowers, and binders, all composed of numerous parts crafted from metal and wood. A cacophony emanated from the blacksmith shop, where parts were tempered and banged into shape. Enormous grindstones, driven by steam-powered overhead belts, whirred continually in the knife department, where the edges of sickle bars were sharpened and serrated. Saws and planing equipment buzzed in the vast series of rooms devoted to woodworking, and a constant clatter arose as towering piles of lumber were replenished. And once in the packing department a drumbeat reverberated as crates in a multiplicity of sizes were hammered shut so that the finished machines—which were shipped in pieces with final assembly completed on-site by McCormick dealers—could be whisked off to farmers in time for the next harvest.9

As he traversed the gaslit factory Cyrus would pick up other sounds, too, from the workers who wielded the tools and ran the machines and, through their skill and muscle, transformed metal and wood into McCormick products. Mostly they had to shout to be heard. Their voices were as varied as the equipment they operated: Irish inflections were common, and then there many with thick German accents, some of whom knew no English at all. When others conversed, their intonations revealed that they had been born in Sweden or Norway. Cyrus would have detected some Polish and Czech being spoken as well, though these languages would be more frequently heard in later decades. All the workers, though, were white men: in the nineteenth century there were relatively few African Americans in Chicago, and as yet no women were present in the factory.

This multiethnic workforce was dominated by skilled craftsmen: blacksmiths, carpenters, machinists, and even painters, who utilized brushes—no spray guns or dips—to coat McCormick implements with their trademark red finish. These workers were capable of performing a variety of tasks and generally did so during the course of their ten-hour day. Common laborers were also employed at the plant—some of them boys as young as twelve years old—but their primary function was to assist the skilled workmen, fetching them supplies or cleaning up what they discarded. Workers moved independently throughout their departments, as they switched machines, hunted down tools, or took an occasional break, while raw material and finished goods spilled over in jumbled piles on the factory floor. There was a system to be discerned within all this hubbub, but to young Cyrus McCormick, with his propensity for order and discipline, it looked like chaos.10

McCormick Works in 1879, in other words, bore almost no resemblance to a modern factory. There were no assembly lines and little of the production process had been standardized. Consequently, just what work was to be done and how fast it would be accomplished was not dictated by technology but was determined largely as a matter of daily negotiation between management and labor. Most employees received bonus pay for each properly finished part they produced—piecework, in other words—which, in theory at least, provided incentive for them to work quickly and competently. But foremen—salaried employees, who were likely native-born Americans—were tasked with driving up output, and they wielded the ultimate weapon: they could discharge workers for any reason. These frontline managers were often the most loathed individuals in the plant.11

The skilled craftsmen at McCormick Works, however, could not be easily intimidated: they were indispensable to production, and they knew it. Nowhere was this more true than in the cavernous foundry, where a large percentage of the parts incorporated in McCormick products were fabricated, and so its steady operation was crucial for proper workflow. In the foundry, a smoldering world unto itself, the heat was nearly unimaginable and the air hung heavy with a toxic haze that settled deep in the lungs. In this infernal arena iron molders, who created the patterns from sand and wood that received molten metal, reigned supreme. To do their jobs well they needed to be swift, strong, and smart: molds improperly constructed, for instance, could explode, propelling flaming shrapnel across the shop. Becoming an iron molder required a long apprenticeship, and teamwork and trust were essential on the job.12

Like many craftsmen in this era, the molders shared a “disciplined ethical code” that governed their interactions with their employers. Because skilled workers knew far more about the processes they were engaged in than their bosses did, they were often able to regulate how much they would turn out, maintaining strict quotas that kept the pace of production within tolerable levels and ensured safer conditions. And, certainly, they would refuse to labor alongside those not recognized as members of their trade. These rules were enforced by the workers themselves—transgressors were ostracized—and underscored the value of cooperation, rather than competition. Skilled workers in the nineteenth century were “unmistakably and consciously group-made men who sought to pull themselves up by their collective bootstraps.” Their ethos imbued them with faith in the dignity of their labor and a recognition of their worth. They were thus loath to suffer disrespect directed at them by their bosses, whether those insults took the form of directives barked out by foremen or wage cuts imposed by top management.13

Within McCormick Works, the iron molders had wielded their strength effectively, for they were the highest paid workers in the plant. And their collective clout was exercised in a manner increasingly relied upon by craft workers in the nineteenth century: through a trade union. These early labor organizations were occupation-specific—printers in one union, carpenters another—and composed only of skilled workers. The molders had first organized at McCormick in the early 1860s, affiliating with the National Union of Iron Molders. Thereafter, the McCormic...