This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Home Parenteral Nutrition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Home parenteral nutrition (HPN) is the intravenous administration of nutrients carried out in the patient's home. This book analyses current practices in HPN, with a view to inform best practice, covering epidemiology of HPN in regions including the UK and Europe, USA and Australia, its role in the treatment of clinical conditions including gastrointestinal disorders and cancer, ethical and legal aspects and patient quality of life.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Home Parenteral Nutrition by Federico Bozzetti, Michael Staun, Andre Van Gossum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IV Practical Issues

21 Adult Fluid and Nutritional Requirements for Home Parenteral Nutrition

St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow, UK

Key Points

• When HPN is considered there need to be clear objectives/targets to be achieved and criteria for stopping.

• Patients having HPN usually eat, so absorb a proportion of the macronutrients, vitamins and trace elements consumed.

• The HPN prescription can be predicted by knowledge of the patient’s remaining gut anatomy and underlying disease(s). Fistula/stomal losses need to be taken into account.

• The estimated energy given commonly falls between 25 and 35 kcal/kg/day before oral/enteral intake is accounted for.

• If abnormal LFTs occur, consideration should be given to reducing the parenteral lipid.

• PN bags should contain vitamins and trace elements.

• An aim of a PN regimen is to give patients 24-h periods without having PN (usually as ‘nights off’).

Introduction

Home parenteral nutrition (HPN) is needed for patients with acute or chronic intestinal failure in whom nutritional and/or water and electrolyte balance cannot be corrected by oral or enteral feeding and in whom parenteral nutrition (PN) is feasible at home (Messing et al., 2001). The nutritional and fluid requirements for patients needing HPN are very variable, largely because these patients continue to eat and absorb some nutrition from their gastrointestinal tract. In addition, they may have large fluid losses from one or more stomas or fistulas. It is relatively unusual for patients to depend totally upon PN for their nutritional requirements unless they have bowel obstruction, a gastric/duodenal stoma/fistula or severe dysmotility. HPN when begun needs to have clear objectives (e.g. treat dehydration/undernutrition, reduce diarrhoea, fit for surgery, etc.) and criteria for stopping (e.g. oral intake resumed, surgical resolution, unethical, etc.). The patients are managed by a multidisciplinary nutrition support team consisting at least of a clinician, dietician, specialist nurse and pharmacist (Nightingale, 2010).

Due mainly to the variability in absorption, gastrointestinal losses and patient activity, the initial requirements are a best estimate and with careful monitoring they are adjusted according to the patient’s state of hydration and target weight. The final HPN prescription will depend not only upon nutritional/fluid requirements, but upon patient preferences.

This chapter shows how patients are stabilized, established on a regimen and how this is adjusted with time. The aim of HPN is to give the patient as near a normal life as possible with as few hours as possible connected to a feed.

Initial Stabilization in Hospital

Anatomical considerations

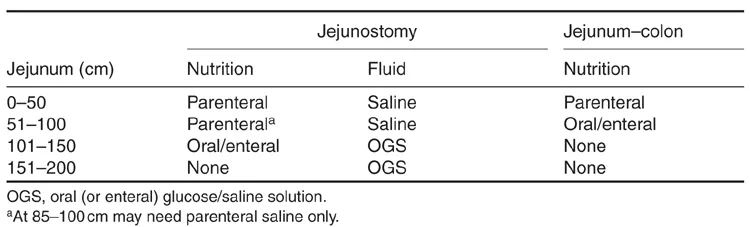

If the gut is short (includes an enterocutaneous fistula that drains all gut contents) but has normal function, then the long-term type of nutritional/fluid support can be predicted (Table 21.1) from knowledge of the small intestinal length in circuit and the presence or absence of a colon in continuity. With time (up to 3 years) patients with a colon in continuity are likely to have a degree of anatomical (villus hypertrophy) and functional adaptation (slowing transit and improvement in some biochemical pathways), so that less parenteral support is needed. This is not the case for patients with a jejunostomy, whose nutritional/fluid requirements change little with time (Nightingale et al., 1992).

Table 21.1. Small bowel length and route of long-term nutrition/fluid. (From Gouttebel et al., 1986; Nightingale et al., 1992; Messing et al., 1999.)

Establishing a regimen

PN requirements are based upon a careful assessment (Table 21.2) which, if the patient is eating, will involve an estimate of how much total fluid/nutrition is being absorbed and lost in secretions.

While the initial regimen will be relatively standardized for the hospital, the prescription at home will be designed around the patient’s wishes/preferences (e.g. nights off feed, duration/timing of feed, frequency of lipid, desired weight, frequency of deliveries, etc.).

Adult Requirements for Water and Electrolytes

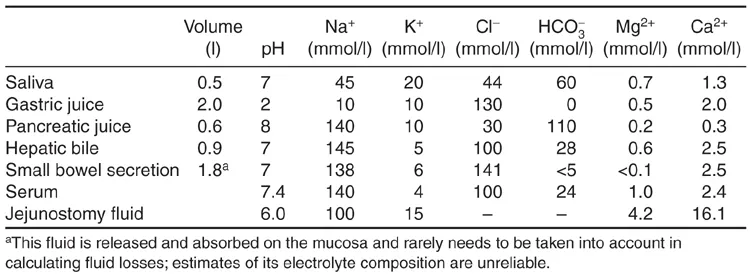

Baseline water and electrolyte requirements are calculated (Tables 21.3 and 21.4) and to this is added an estimate of intestinal losses (Table 21.5). The losses will vary as medical and dietary therapy is maximized (e.g. for high-output jejunostomy: restricting oral hypotonic fluid restriction, sipping an oral glucose/saline solution and taking anti-diarrhoeal and anti-secretory drugs).

Standard prescribing ranges that assume normal organ function and no intestinal losses are used to estimate electrolyte requirements (Table 21.4). Depending on the clinical situation and intestinal anatomy, additional sodium, potassium and magnesium may be required. Table 21.5 gives some indication of the amount of sodium/potassium lost in different gastrointestinal secretions.

Table 21.2. Assessment prior to starting PN.

Underlying illness and co-morbidities Gastrointestinal anatomy (e.g. length of small bowel, fistula(s), etc.) Fluid status (e.g. gut losses, oral/intravenous intake, urine output, etc.) Nutritional status (BMI, percentage weight loss, mid-arm muscle circumference) Current oral/enteral intake Outcome targets |

Table 21.3. Estimation of fluid (water) requirements before gastrointestinal losses are taken into account. (From Tyler, 1989.)

18–60 years old | 35 ml/kg body weight |

>60 years old | 30 ml/kg body weight |

Pyrexia | Add 2–2.5 ml/kg body weight for each °C body temperature is above 37°C |

Table 21.4. Estimation of electrolyte requirements before gastrointestinal losses are taken into account. (From Micklewright and Todorovic, 1997.)

Sodium | 1–1.5 mmol/kg body weight |

Potassium | 1–1.5 mmol/kg body weight |

Magnesium | 0.1–0.2 mmol/kg body weight |

Calcium | 0.1–0.15 mmol/kg body weight |

Phosphate | 0.5–0.7 mmol/kg body weight or 10 mmol/1000 kcal |

Chloride | 1–1.5 mmol/kg body weight |

Adult Nutritional Requirements

Energy

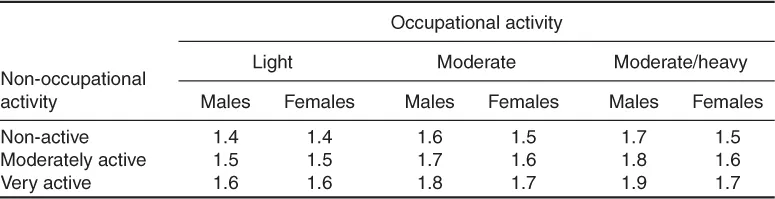

Predictive equations can be used to estimate basal metabolic rate (BMR), such as those of Harris and Benedict (1919), Schofield (1985) and currently Henry (2005) (Table 21.6). A physical activity level (Table 21.7) and stress factor if appropriate are added to the BMR to give the total energy requirement. Additional energy (400–1000 kcal) can be added if weight gain is needed.

Care should be taken not to provide excess energy as occurred in the 1970s and 1980s and resulted in hyperglycaemia, liver function test abnormalities and high rates of infection.

The estimated amount of energy commonly falls within the range 20–35 kcal/kg body weight/day (A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and the Clinical Guidelines Task Force, 2002; NICE, 2006; Staun et al., 2009), and only rarely more than 40 kcal/kg body weight/day (Koea et al., 1995). Oral and enteral intake is taken into account with an estimate of a malabsorption factor. In patients with a short bowel and jejunostomy at 100 cm from the duodenojejunal flexure, approximately 40% of the oral diet is absorbed and at 50 cm only 20% (Nightingale et al., 1990).

Table 21.5. Approximate daily volume and composition of intestinal secretions produced in response to food.

Table 21.6. Equations for estimating BMR from gender, age and weight (W). (From Henry, 2005.)

Gender | Age (years) | BMR (kcal/day) |

Male | 18–30 | 16.0 W + 545 |

30–60 | 14.2 W + 593 | |

60–70 | 13.0 W + 567 | |

70+ | 13.7 W + 481 | |

Female | 18–30 | 13.1 W + 558 |

30–60 | 9.74 W + 694 | |

60–70 | 10.2 W + 572 | |

70+ | 10.0 W + 577 |

Energy and protein requirements in obesity (body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2) are adjusted to avoid overfeeding (Table 21.8). Regular anthropometry in this patient group is used to monitor changes in body composition, in particular preventing rapid muscle loss.

Nitrogen

Large nitrogen losses are documented in sepsis, major trauma and burns. An unstressed patient with normal organ function will require 0.14–0.2 g nitrogen/kg body weight/day (Elia, 1990). If a patient has a low muscle mass and requires more nitrogen, 0.3–0.6 g nitrogen/kg body weight/day may be used (Keys et al., 1950).

It has been customary in some countries, including the UK, not to include nitrogen energy (usually 200–300 kcal) in the quoted total energy in a regimen (unlike with enteral nutrition, where the total energy quote includes the nitrogen energy).

Table 21.7. Guidelines for estimating energy and protein requirements in the unstressed/clinically stable patient. (From A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and the Clinical Guidelines Task Force, 2002; NICE, 2006.)

Energy | Protein |

25–35 kcal/kg body weight/day | 0.8–2 g protein/kg body weight/day |

Obese patients | Obese patients |

BMI > 30 kg/m2 who are not metabolically stressed: calculate energy requirements as normal and subtract 400–1000 kcal/day for a decrease in energy stores | BMI > 30 kg/m2: use 75% of the value estimated from actual weight BMI > 50 kg/m2: use 65% of the value estimated from actual weight |

Table 21.8. Calculated physical activity level (PAL) of adults; BMR is multiplied by PAL give total energy requirements. (From Department of Health, 1991.)

Energy sources

Carbohydrate

Carbohydrate and lipid are the main energy sources in PN. Glucose requirements can be set at 3–6 g/kg body weight/day (Staun et al., 2009); being aware that excess glucose provision can cause problems, particularly hyperglycaemia or abnormal liver function tests. Glucose oxidation rate can be calculated (4–7 mg × kg body weight × 60 × 24/1000 × 4) to give an indication of the maximum amount of glucose that can be utilized. However, it is possible to exceed these requirements in malnourished patients requiring weight gain. While the ratio of glucose to lipid may be 50:50 (or 60:40) at first, this is reduced within the first month to be approximately 70–85% from glucose and 15–30% from lipid for long-term HPN (Staun et al., 2009).

Lipid

Most patients are provided with some lipid, in particular in those patients with little enteral intake. Long-term intravenous lipid provision is kept below 1 g/kg body weight/day (500 ml of Intralipid® provides 550 kcal and usually in long-term HPN fewer than three of these are given per week), as above this chronic cholestasis is common (Cavicchi et al., 2000). A 20% soy-based lipid emulsion given weekly is adequate to prevent essential fatty acid deficiency; if a patient is having no lipid and has a dry skin, he/she can apply 10 ml sunflower or safflower oil to the skin daily (Press et al., 1974; Miller et al., 1987).

If a central line catheter tip becomes high (in the superior vena cava or brachiocephalic vein) and replacement is not an immediate option, the feed may be adjusted to have a much lower osmolality (to reduce the risk of venous thrombosis) by relying on a high lipid, low glucose content.

Micronutrients

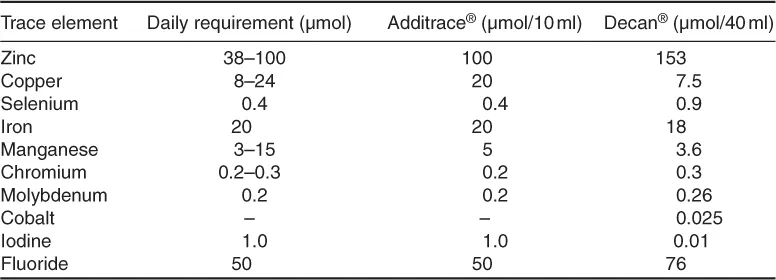

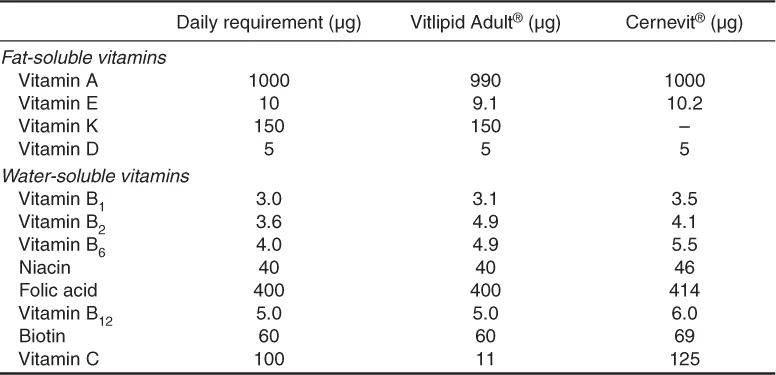

Vitamins and trace elements are included in the HPN prescriptions (Tables 21.9 and 21.10), especially if the patient has no enteral nutrition or poor gastrointestinal absorption. The commercial preparations used in PN generally provide amounts in excess of basal requirements as they are intended for patients who are nutritionally depleted. Depending on nutritional status and enteral absorption, these preparations can be given daily or on alternate days.

Additional iron, vitamin D and selenium supplementation may be needed in addition to PN if serum levels remain low.

Adjustment of Regimen during Hospital Stay and the Final Prescription for HPN

Often during the hospital stabilization period sepsis is treated and a stoma/fistula output becomes more established, as does the patient’s oral intake. Fluid balance usually dominates the clinical picture and a stable regimen with regard to water, sodium and magnesium is gradually established. Fluid balance, weight, clinical symptoms/signs of dehydration (thirst/dry mouth)/overhydration (oedema, raised jugular venous pressure) are assessed daily and blood tests (renal and liver function) done as needed (usually two or more times per week). A urine output greater than 1 l/24 h with random urine sodium level of 20 mmol/l or more is desirable. The energy given depends upon the oral intake, the estimated absorption (which can be better predicted if the bowel length has been measured either at surgery or more commonly radiologically) (Nightingale et al., 1991), blood glucose and weight/muscle mass (which should increase in hospital).

Table 21.9. Daily requirements and sources for parenteral micronutrients. (From American Medical Association, 1979a.)

Table 21.10. Daily requirements and sources for parenteral vitamins. (From American Medical Association, 1979b.)

The HPN prescription is formulated towards the end of the patient’s hospital admission when he/she is medically stable and consuming a similar amount of f...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- I Parenteral Nutrition: An Overview

- II Clinical Conditions

- III Complications

- IV Practical Issues

- V Paediatrics

- VI Miscellaneous Aspects of Home Parenteral Nutrition

- Index

- Footnotes