This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Exotic Fruits and Nuts of the New World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A major reference work on exotic and underutilised fruits and nuts of the New World. While many of these are well known in the local markets and in Spanish-language literature, they have rarely been brought to the attention of the wider English-speaking audience, and as such this book will offer an entirely new resource to those interested in exotic crops.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Exotic Fruits and Nuts of the New World by Odilo Duarte, Robert E Paull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Anacardiaceae

The Anacardiaceae includes many fruit-producing genera including Spondias (S. mombin, the hog plum, S. dulcis, the ambarella, S. purpurea, the red mombin, and others), Mangifera (M. indica, the mango, and several other species), Pistacia (P. vera, the pistachio nut, and ornamental trees) and Schinus (S. molle, the Peruvian pepper tree, and S. terebinthifolius, the Brazilian pepper tree). This chapter will cover the cashew, which is widely grown for both its fruit and its nut, and two Spondias species that are now distributed worldwide.

Cashew

Cashew, Anacardium occidentale L. (Anacardiaceae), is one of the important edible nuts consumed worldwide. The cashew fruit (swollen receptacle or pseudofruit) is also important and is frequently consumed fresh, and made into a juice and other products (Donadio, 1983). The Latin name means inverted (ana) heart (cardium) and the Portuguese name cajú comes from akajú, meaning yellow, in a native language. Common names include: in Arabic habb al-biladhir; in Bengali hijlibadam, hijuli; in Hindi kaaju; in Tamil mindiri; in Nepali kaaju; in Malay gajus, jambugolok and jambu mede; in Swahili mbibo and mkanju; in Thai mamuang, yaruang; in Chinese yao guo and yao guo shu; in French acajou a pommes, noix-cajou, noix d’acajou, pomme d’acajou; in Portuguese cajú and cajueiro; in Spanish anacardo or marañón; jocote marañon in Central America, cajuil in the Dominican Republic, casho or cajú in Peru; merey in Venezuela and Colombia. Synonyms include Acajuba occidentalis Gaertn., and Cassuvium pomiferum Lam.

Several species of Anacardium are similar to cashew, with a fleshy receptacle and a nut (Donadio et al., 2002). Some of these species, such as A. giganteum, A. negrense, A. othonianum, A. humile and A. microcarpum, are regionally important in Brazil for their nuts and fruit. A. microcarpum is a species native to the north-east of Brazil, where it is called cajui or caju miniaturia (“miniature cashew”) and could become important commercially. The fruit of A. microcarpum is about a third the size of cashew and the pseudofruit is somewhat acid. Other species found in Brazil according to Prabhakaran-Nair (2009) are: A. nanum, A. corymbosum and A. spruceana. On the western side of the Andes A. excelsum is the only species found.

Origin and distribution

Brazil is normally considered the center of origin of cashew (de Almeida et al., 2003), since the largest number of varieties of the genus Anacardium are found in north-eastern Brazil. Johnson (1973) considers that the state of Ceará is where cashew originated. Prabhakaran-Nair (2009) indicates central Amazonia and the Planalto of Brazil as the probable places of origin. The indigenous people of Brazil consumed the nut and the swollen pedicel called the “cashew apple”. They fermented the juice squeezed from the cashew apples to produce wine and roasted the nuts over a fire, thus eliminating the toxic oil from the seed coat. The trees are often found growing wild on the drier sandy soils in the central plains of Brazil and are cultivated in many parts of the Amazon rainforest (Sivakumar and Pai, 2008).

The Portuguese introduced the cashew to India in 1590, possibly through Goa, where it was grown for producing wine and brandy. Later cashew was introduced to the rest of Asia. The Portuguese also introduced the cashew to their colonies in East Africa where it became naturalized and now grows wild along the Mozambique coast. From here, it was introduced to other East African countries: Tanzania and Kenya. Cashew is now grown in tropical regions from South America to the West Indies to Florida, Africa and India.

The cashew nut entered international commerce at the beginning of the 20th century when it became a very important nut after almonds. The planted area has increased in many countries and between 1995 and 2004, world cashew nut production doubled as a result of incentives in producing countries and foreign market expansion. This expansion has slowed in the last few years. Vietnam saw a fourfold increase in the area planted to cashew and in its nut production between 1995 and 2004 (FAO, 2006). In 2004, the total area cultivated in the world was 3.09 million ha with a production of 2.27 million t (FAO, 2006). Prior to 2004, India was the largest producer of raw nuts and now is in third place with 544,000 t after Vietnam, 961,000 t and Nigeria, 594,000 t. India is still the largest processor and exporter, and the second largest consumer. India also imports around 200,000 t of raw nuts, mostly from African countries. The imported nuts are processed and India exports about 95,000 t of clean kernels. Productivity in India is improving with the use of superior varieties and better technology. Similarly, productivity in Brazil with its 691,000 ha in production and currently low yields is increasing with more technically managed orchards. The north-eastern states of Ceará, Piaui and Rio Grande do Norte account for more than 90% of Brazil’s cashew production.

Ecology

Soil

The ideal soils seem to be those on flat or slightly hilly land, with light to medium texture, free from stones and aluminum toxicity, with good drainage, high in organic matter and nutrients, pH of 5.0 to 6.5 and no impervious layer in the first 100 cm, such as virgin forest soils (Crisóstomo et al., 2007; Sivakumar and Pai, 2008). Soils to avoid are those that are gravelly, saline, shallow, with an underground water table deeper than 10 m or shallower than 2 m, and areas subjected to periodic flooding (da Silva, 1998). Alluvial well-drained soils normally give good production.

Cashew is frequently grown on marginal soils and also on wasteland unsuitable for other economic crops. The tree is found along sandy sea coasts, fairly steep lateritic slopes or rolling land with shallow top soils in India; alluvial soils in Sri Lanka; ferruginous soils in East and West Africa, Brazil and Madagascar; and volcanic soils in the Philippines, Indonesia and the Fiji Islands. In Brazil, especially in the north-east, the majority of cashew grows on latosols, argisols and quartz-sands that are fairly deep but poor in fertility with a pH of 4.5 to 5.5. It is very popular among poor farmers who can grow a crop of cashew without much tree management, though yields are very low. Many small farmers intercrop cashew with annual crops to obtain more income from their land.

Rainfall

Cashew grows best in a warm, moist, tropical climate with a well-defined dry season of 5–7 months that coincides with flowering and fruiting (de Almeida et al., 2003), followed by a wet season of 5–7 months (1,000–2,000 mm rainfall). In regions with two dry seasons, the tree will flower twice, and with rainfall year round it will flower continuously. In areas with 500–700 mm rainfall, it performs well if it has access to an adequate underground water supply (Ohler, 1979). Cashew can also grow in places with up to 4,000 mm rainfall though a dry period is needed during flowering and fruit set. When flowering occurs during heavy rains and with humidity above 85%, flower diseases, commonly anthracnose and mildew, cause serious losses (da Silva, 1998). In most places, the plant grows without irrigation though it does respond very well to summer irrigation.

Cashew develops well in humidity between 70% and 80%, but also grows well in regions with relative humidity of 50% if there is good soil moisture or with irrigation (Crisóstomo et al., 2007). Very low humidity during flowering reduces stigma receptivity or pollen viability and induces small fruit drop (da Silva, 1998).

Temperature

The tree is found growing between 27ºN and 28ºS, though yields are higher between 15ºN and S (Crisóstomo et al., 2007). Plantations can be found at altitudes of up to 1,200 m in the tropics (Vargas et al., 1999). Tree growth occurs between 16 and 40°C, with an optimum of 26–28ºC. Damage to young trees and flowers will occur below 7°C and above 45°C. Prolonged cool temperature does damage adult trees, although they will survive to 0°C for short periods.

Light and photoperiod

The plant prefers to grow in full sun. The optimum total sunshine is 1,285 h, or 9 h day-1 during the flowering and fruit set period (Sivakumar and Pai, 2008). Flowering is unaffected by day length.

Wind

Winds up to 3 m s-1 are generally not a problem. In areas with wind speeds greater than 7 m s-1 young plants have to be protected by tying them to a stake and installing windbreaks. During flowering, dehydration caused by strong winds can be a problem for fertilization and fruit set. Flower and young fruit drop as well as trees being blown down are also possible (da Silva, 1998).

General characteristics

Tree

The cashew is an attractive evergreen with smooth bark and is an erect, low-branching tree, 4–16 m tall, with a spreading canopy that can be as wide as it is tall. The lower limbs, if not pruned, sometimes touch the ground. Under sub-optimal conditions the tree will grow to 5–8 m and the stem will be tortuous, while under good conditions it is straight. In deep soils, the tree can have a deep and well-defined taproot and the lateral roots will extend beyond the drip line of the canopy. The depth of the main and lateral roots and their distribution are affected by the soil type. In good soil conditions the taproot can go down to 10 m and 82% of the root system is in the upper 30 cm of soil (de Almeida et al., 2003). In Brazil, two types of cashew trees are recognized. The common cashew grows to heights of 10–12 m and can reach 14–16 m, and the canopy diameter can vary from 10 to 14 m. The other type grows to 4–6 m, with a canopy diameter of 6–8 m (de Almeida et al., 2003).

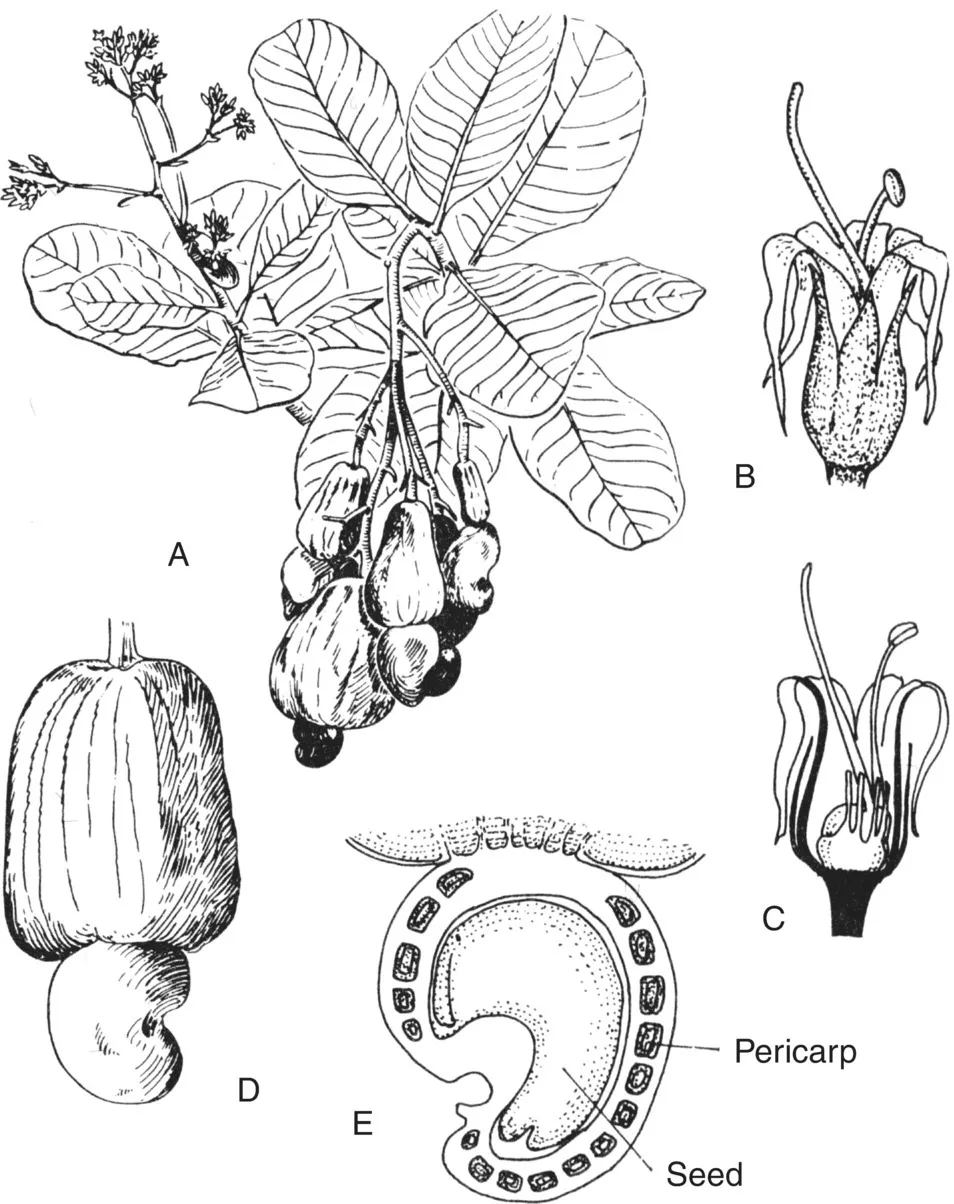

The oblong-oval or obovate leaves are alternate, simple, entire and fairly large (8–20 cm by 6–12 cm). The leaves are glabrous and have a short petiole, prominent veins and come in terminal clusters (Fig. 1.1). They are normally reddish or golden when young turning into a light green color and leathery texture as they mature.

Fig. 1.1. Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) nut and “apple” showing (A) leaves, panicle and fruit cluster, (B) and (C) flowers, (D) fruit and swollen peduncle “receptacle” called the “apple” and (E) transverse section through the fruit showing the seed and the pericarp (used with permission from León, J. (2000) Botánica de los Cultivos Tropicales. Editorial Agroamérica, Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA), San José, Costa Rica).

Flowers

Cashew flowers are either male or hermaphrodite (andromonoecious, perfect), like those of mango, and are borne in 15–25 cm terminal panicles (Fig. 1.1A). Each panicle can have 120–1,100 flowers (average 500). The hermaphroditic flowers are larger than the male flowers. The individual flowers are sweet-smelling and small, with usually five yellowish-green or yellowish-pink petals about 1.0–1.5 cm, five 0.5 cm sepals and ten stamens. One stamen is about 12 mm long and the other nine are about 4 mm long (Fig. 1.1C). Early flowers are mostly male with perfect flowers being generally produced about 1 month later on the panicle. One perfect flower is found for every 6–28 male flowers, depending on the genotype, climate and other factors.

The petals turn from white or creamy-white or pale greenish with red stripes to pink or red and become recurved as the flower fully opens. The flowering period lasts 2–3 months and occurs normally during the dry season following rains, with the fruit maturing 45–75 days later.

Pollination and fruit set

Flowers normally open between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. with a peak at noon. The stigma is receptive to pollen only on the day of anthesis, but pollen is released later, allowing both cross-fertilization and self-pollination. Studies to date have implicated both wind and a variety of insects as pollinating agents, but there is no information on their relative importance (de Almeida et al., 2003). Since the flowers are scented and pollen is sticky, insects may play an important role in pollination. Beehives placed in or near ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Anacardiaceae

- 2 Calophyllaceae, Clusiaceae and Cactaceae

- 3 Myrtaceae

- 4 Sapotaceae

- 5 Solanaceae

- 6 Sapindaceae

- 7 Passifloraceae and Caricaceae

- 8 Arecaceae

- 9 Other Families

- Index