![]() PART I

PART I![]()

1 Adventure Tourism

Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the beginning think what may be the end.

Edward Whymper, Scrambles Amongst the Alps

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter the reader will be able to:

• differentiate the key skills required to be an effective adventure tourism operator; and

• appraise the different aspects of adventure tourism and its associated definitions.

Chapter Overview

Adventure is a key element in the human psyche even if this is only exploring the locale or participating in a novel journey or new activity. Humans need adventure to compensate for boredom, a state that ensures atrophy of the human condition and spirit. It is therefore unsurprising that the adventure tourism market is buoyant and growing and since the 1950s has developed exponentially.

This book was conceived as a reader for many aspects of adventure tourism management. The author has taught and delivered adventure tourism courses for some considerable time and felt that there was a need for a new book covering a more universal view of adventure tourism today, whilst also trying to explore the more practical and useful elements that this market faces, including future challenges. Adventure is risk and risk is the essence of living: without risk we are dead. Adventure, then, can be considered to be the lifeblood of psychological/physical challenges which most people need to live a fulfilled life.

What is Adventure Tourism?

Adventure has a long history in human endeavour, perhaps from the first footsteps of human exploration out of Africa several hundred thousand years ago. Yet the foundations of the current market and current experiences were set in the late 1940s, based upon a new optimism that followed the end of the Second World War. Many of the present practices of adventure in the UK were to be found in organizations such as the Outward Bound Movement and the Duke of Edinburgh Awards Scheme. The conquering of Everest in 1953 was perhaps the pinnacle of this period of adventure, bringing a new dawn and excitement to the adventure tourism movement.

The 1950s and the mass tourism markets of the 1960s expanded the horizons for adventure tourism offering new types of activities. The 1980s and 1990s saw further exponential growth of adventure centres and educational field centres, all connected to adventure activities. The market was changing too, with a far more eclectic and splintered focus. This can be seen within the paradigm of postmodernist developments, creating a clear change in the expectations and activities of tourists. Much of this has been helped by advancing technology and new equipment, together with a change in holiday expectations. There has been a transformation of the mass tourism market and a clear change with tourists wanting to experience something extra. Many holiday packages now include some aspect of adventure or an activity to add excitement to the routine of mundane beach activities. Initial taster sessions supported by holiday snaps of paragliding, surfing or some other unusual activity have driven the demand for adventure activities while on holiday.

It is also evident that some destinations have recognized the demand for specific types of activities and have specialized in order to offer new experiences, difficult to find elsewhere. New Zealand and its South Island are well known for adventure tourism and destinations such as Dunedin and Queenstown have a global adventure tourism reach. Perhaps the single activity that most famously represents New Zealand adventure tourism is that of bungee jumping, though this, too, has become passé. Bungee jumping was first developed in the UK, one of the first jumps being made off Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol in 1979 (BBC, 2014), emulating a ritual of Vanuatu Islanders of the South Pacific who jumped off scaffolds with vines attached to their legs.

The growth of adventure tourism has meant that many extreme activities have now become more mainstream. For example, surfing, which was once the preserve of individuals on the margins of society, has now become somewhat ‘vanilla’ and most people visiting a seaside with surfing beaches will have attempted it. But is this adventure and what exactly is meant by adventure tourism?

It is suggested that many holidays are in many respects an ‘adventure’ and that adventure is not necessarily an activity but a ‘state of mind and attitude’. Certainly it is posited that to many people the phrase ‘adventure tourism’ probably produces an image of individuals struggling against nature and the elements, whilst engaging in an activity that would involve ‘risk and hazard’, which could result in fatality or serious injury. This image is now somewhat dated and the current adventure market encompasses far softer and slower forms of adventure

It is evident that adventure tourism has a wide reach and to define it and pigeonhole it within a narrow frame is not appropriate or helpful given the current adventure tourism market. As with most definitions, the years of tourism development have changed the original delineation, incorporating new perspectives.

Definitions

The definition of adventure tourism taken for this book relates to ‘any activity or journey that creates a sense of risk and thrill for the person participating in an activity which may have a degree of risk of injury’. This can encompass extreme sports and activities such as diving, skydiving, surfing and mountaineering through to journeys that expose the traveller to varying degrees of risk, but would exclude theme parks (though this might be contested). Adventure tourism should involve an activity that provides the participant with a degree of ‘perceived risk’ outside of their normal place of residence, including aspects of slow tourism.

Adventure tourism can include activities that also carry low levels of exposure to risk, taking place at tourist destinations. For example, driving large 4×4 vehicles over rough and rugged terrain could be seen as an adventure but with minimal personal risk (Fig. 1.1), as the tourist is protected from the elements. Certainly, in Iceland these types of tours are being offered and are connected with the notion of adventure tourism. Iceland has some of the largest off-road vehicles and these are often used on glaciers and rough terrain that other vehicles would find impossible to traverse. This type of adventure can be seen simply as the experience of travelling from point A to point B over terrain that is different from normal metalled roads carrying some potential risk. The Icelandic landscape can be extreme and extreme conditions such as high winds, quicksands, crevasses and volcanic dust storms are regular occurrences. However, this type of adventure requires low levels of physical activity, which is something of a paradox given a common assumption of adventure tourism that physical activity is usually related to an adventure. Although vehicle accidents are a risk, riding in a vehicle provides relative protection from the elements and an ‘illusion of safety’.

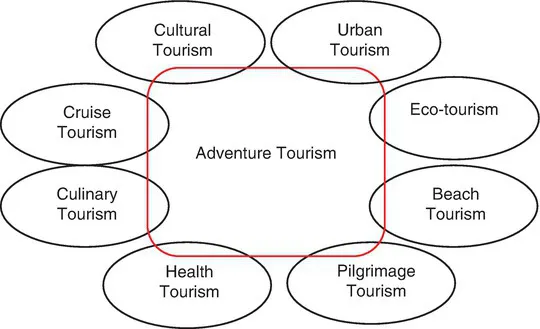

The breadth of adventure tourism is large and presents challenges for a definitive definition (Fig. 1.2). For example, ‘slow’ tourism can be a part of adventure tourism. Once again this does not necessarily involve high levels of risk: ‘glacier walking’ might be seen as an activity that has a perception of high risk, but the reality of injury and death is low when walks are guided. Likewise, river rafting, if correctly supervised, carries a low risk of injury and death. These types of activities might be defined as ‘soft’ adventure tourism.

The terms ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ adventure are frequently used within the adventure market, although obtaining a conclusive definition is ambiguous, as both terms are somewhat intuitive rather than absolute. The perception of ‘Hard’ adventure is that it involves a high risk of injury or death. This partly explains why its market (caving, climbing, heli-skiing, kite surfing, paragliding) is considered small and limited, restricted to high risk adventurers, who make up a small proportion of the total adventure market. However, there are clear aberrations within the categorization of adventure sports and ATTA note that surfing, snowboarding/skiing and rafting are considered to be ‘Soft’ adventure; intuitively, however one would consider these activities to be more associated with extreme adventure (ATTA & GWU 2013). This clearly suggests that there is a degree of subjectivity when categorizing ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ adventure. The specifics of the sport and the destination can also be a means by which to define them. e.g. surfing Mavericks California (high risk and high skill levels) compared to beaches in Cornwall (lower risk and skill levels).

Conversely, activities that consumers assume to be low risk are in fact high risk. Horse riding is not necessarily seen as being dangerous, yet statistics reveal that death and serious injury is a relatively high risk for many horse riders (BBC, 2009).

Adventure does not have to be linked to high-risk activities. It can be viewed in many psychological contexts and, depending upon the adventurer’s personality, can be very different for each individual. This means that ‘adventure’ is a perceptual frame and it is not the nature of the activity that is necessarily important, but rather the destination, the activity and nature of the perceived risk that are critical when defining adventure tourism. As will be shown in this book, adventure tourism sports are constantly evolving, pushing the ‘experiential’ boundaries and changing definitions of adventure tourism. As with many definitions related to tourism, they are temporal and affected by advances in technology and society.

Low Activity Input

As noted above, adventure tourism usually evokes the perception of an activity with high risk levels, but the industry encompasses a broad array of risky activities, including sports that the general public would not readily categorize as an adventure; currently, the growth of slow tourism is an example of this. However, this too can be a part of adventure tourism, especially if the journey is undertaken in wilderness and locations that are extreme and isolated.

Adventure journeys by vehicles are another example of low-risk soft adventure, though it will depend upon the chosen route, as some offer perilous tracks and high fatalities. Some routes in developing countries will have roads or tracks requiring a high skill level in order to avoid tragedy. For example:

The path from La Paz to Coroico, Bolivia, is a treacherous one. The North Yungas Road weaves precariously through the Amaz...