eBook - ePub

Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Continued geographic expansion of dengue viruses and their mosquito vectors has seen the magnitude and frequency of epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever (DF/DHF) increase dramatically. Recent exciting research on dengue has resulted in major advances in our understanding of all aspects of the biology of these viruses, and this updated second edition brings together leading research and clinical scientists to review dengue virus biology, epidemiology, entomology, therapeutics, vaccinology and clinical management.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever by Duane J Gubler, Eng Eong Ooi, Goro Kuno, Subhash Vasudevan, Jeremy Farrar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Dengue Viruses: Their Evolution, History and Emergence as a Global Public Health Problem

Introduction

Dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DF/DHF) are caused by dengue viruses (DENV), which form the dengue complex in the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae (Lindenbach et al., 2007). There are four antigenically related, but distinct dengue virus serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4), all of which can cause mild to severe and fatal disease in humans (Gubler et al., 2007). A proposed new serotype (DENV-5) has recently been described from Malayisa (Nikolaos Vasilakis, personal communication, October 2013). This is a sylvatic virus most closely related to DENV-4. At this time, the public health implications of this new serotype are uncertain. The epidemiologic, evolutionary, biologic, and immunologic relationships of these viruses with each other and with other flaviviruses are discussed in detail in other chapters of this book. All four original serotypes, however, have similar natural histories, including an enzootic cycle involving nonhuman primates and canopy dwelling mosquitoes in Asia, and an urban cycle involving humans as the primary vertebrate host and Aedes mosquitoes of the subgenus Stegomyia as the primary mosquito vectors globally in the topics. A DENV-2 sylvatic cycle similar to that in Asia has also been documented in Africa. This chapter reviews the history of dengue viruses, emphasizing those aspects that help explain the emergence of severe and fatal dengue disease as a global public health problem in the waning years of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century.

Origin and Natural History

Dengue viruses

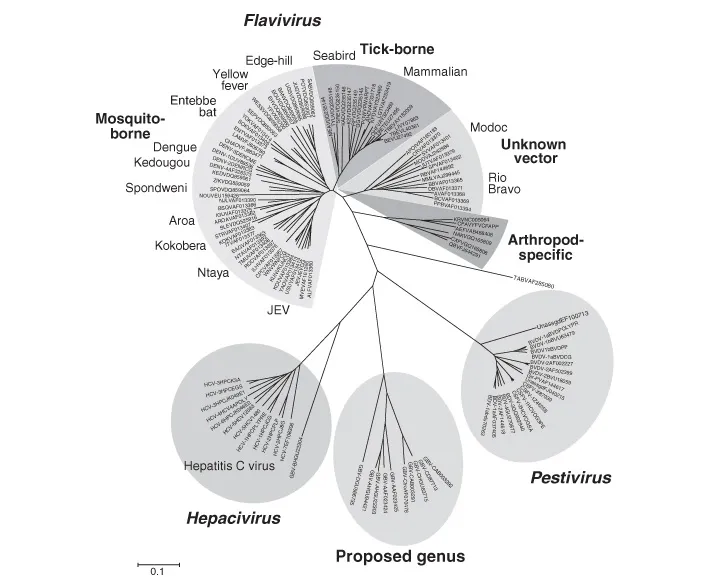

The origin and evolution of the dengue viruses have been the subject of much discussion in recent years. Some early authors speculated an African origin and subsequent distribution around the world with the slave trade (Hirsch, 1883; Smith, 1956; Ehrenkranz et al., 1971). It has also been proposed that the viruses may have originated in a forest cycle involving lower primates and canopy-dwelling mosquitoes in the Malay Peninsula (Smith, 1956; Rudnick and Lim, 1986; Halstead, 1992; Gubler, 1997). More recent studies based on sequence data of dengue and other flavi-viruses have suggested an African origin of the progenitor flavivirus, which ultimately branched into three genera, Flavivirus, Pestivirus, and Hepacivirus. In addition, two groups of unassigned viruses, GBV-A and GBV-C, have been placed in the family (King et al., 2012; Chapter 17, this volume). In this chapter, the use of flavivirus refers only to members of the genus Flavivirus.

The dengue viruses belong to the genus Flavivirus, which branched into four subgroups: (i) the insect-specific viruses that have only been isolated from various mosquito species; (ii) the vertebrate viruses that have no known arthropod vector, and which have been isolated only from rodents and bats; (iii) the mosquito-borne viruses; and (iv) the tick-borne viruses (Fig. 1.1; Kuno et al., 1998; Gaunt et al., 2001; Gould et al., 2003; Gubler et al., 2007; Crabtree et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012). It is still uncertain which flavivirus group is the oldest. Given the large number of insect viruses identified in mosquitoes in recent years, which have tentatively been placed in the genus Flavivirus (Crabtree et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2012; King et al., 2012), it seems plausible that the ancestral flavivirus was a mosquito or tick virus that diverged by adapting to a variety of vertebrate hosts, including rodents, birds, bats, and nonhuman primates. From these early associations, the no-known vector, tick-borne encephalitis, and mosquito-borne (yellow fever, dengue, and Japanese encephalitis) subgroups arose. That the tick-borne and mosquito-borne viruses had a common ancestor is supported by the fact that several mosquito-borne flaviviruses (Koutango, Saboya, West Nile, and yellow fever) have all been isolated from ticks (Monath and Heinz, 1996; Billoir et al., 2000). Also, it has been reported that some tick-borne viruses replicate in mosquitoes or mosquito cell cultures (Clifford et al., 1971; Kisilenko et al., 1982; Lawrie et al., 2004a,b; Kuno, 2012a; Madani et al., 2012). On the other hand, a comprehensive replication study of 66 flaviviruses in mosquito, tick, and vertebrate cell cultures by Kuno (2007a) showed conclusively that there is strict host range specificity for viruses in the four subgroups, and that the conventional classification based on epidemiologic and phylogenetic relationships is correct.

Fig. 1.1. Phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationship of the genus Flavivirus.

It is not known whether the divergence of the four flavivirus subgroups occurred in Africa, in Asia, or in both areas. However, the fact that the dengue, Japanese encephalitis, and tick-borne subgroups are all predominantly Old World viruses suggests that these groups diverged and evolved to their present form in Asia. The Asian origin of dengue viruses is supported by both ecological and phylogenetic evidence (Gubler, 1997; Vasilakis and Weaver, 2008). Thus, all four dengue serotypes have been documented in a sylvatic cycle involving nonhuman primates and aboreal mosquitoes in the Malay Peninsula (Rudnick, 1978), whereas only DENV-2 has been documented in a similar cycle in Africa (Cornet, 1993). The recent isolation of a virus tentatively identified as a new serotype of dengue (DENV-5) in Malaysia supports this Asian origin of dengue virus. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis places the Asian sylvatic dengue virus strains in a deep position in the phylogenetic tree (Wang et al., 2000; Twiddy et al., 2002; Vasilakis and Weaver, 2008). That these viruses had an Asian origin is also supported by serosurveys conducted in rural communities of Malaysia in the early 1950s, which showed that the prevalence of DENV-1 neutralizing antibody was similar in people living in diverse ecologic situations, ranging from the forest fringe to coastal swamps (Smith, 1956). Antibody rates increased with age, as would be expected in a disease-endemic area; epidemics were rare or absent in these areas, and Aedes aegypti was not present. Moreover, significant prevalence rates of DENV-1 antibody in monkeys and other canopy-dwelling animals were observed. Smith (1956) suggested that Aedes albopictus, which occurs in large numbers in the forest fringe, was the connecting link for rural dengue in man. It is likely that the four (five?) serotypes of dengue viruses infecting humans evolved in the sylvatic cycle and moved into villages and towns after urban settlements had become common.

Regardless of the geographic and evolutionary origin, the data collectively suggest that the dengue viruses most likely evolved as viruses of mosquitoes before becoming adapted to lower primates and then to humans, an estimated 1500–2000 years ago (Wang et al., 2000; Holmes and Twiddy, 2003; Weaver and Barrett, 2004). Biologically, dengue viruses are highly adapted to their mosquito hosts, being maintained by vertical transmission in mosquito species responsible for sylvatic cycles, with periodic amplification in lower primates. As noted above, forest cycles have been documented in Southeast Asia and Africa, and possibly in Sri Lanka, India, Vietnam, and China. These cycles involve several species of lower primates and three subgenera (Stegomyia, Finlaya, and Diceromyia) of canopy-dwelling mosquito species of the genus Aedes (Rudnick and Lim, 1986; Cornet, 1993; Vasilakis and Weaver, 2008).

Discovery of the agents

Although it had been shown that dengue fever was caused by a filterable agent early in the 20th century (Ashburn and Craig, 1907; Siler et al., 1926), the first dengue viruses were not isolated until 1943, during the Second World War. Dengue fever was a major cause of morbidity among Allied and Japanese soldiers in the Pacific and Asian theaters (Sabin, 1952; Kuno, 2007b; Hotta, 2011). Both the Japanese and the US military established commissions to study dengue fever and both groups were successful in isolating the virus. Hotta and Kimura were the first to isolate the virus in 1943, by intracranial inoculation of serum from an acutely ill patient into suckling mice (Kimura and Hotta, 1944; Hotta and Kimura, 1952; Hotta, 2011). Unfortunately, this work was published in an obscure Japanese journal and was not recognized for years. Sabin and his colleagues similarly isolated viruses from US soldiers stationed in India, New Guinea, and Hawaii in 1944 (Sabin and Schlesinger, 1945; Sabin, 1952). This group also developed a hemagglutination-inhibition test for serology, and was able to show that some virus strains from all three geographic locations were antigenically similar. This virus was called dengue 1, and the Hawaiian virus was designated as the prototype strain (Haw-DENV-1). Several isolates of another antigenically distinct virus strain from New Guinea were called dengue 2; the New Guinea ‘C’ strain was designated as the prototype virus (NG‘C’-DENV-2). The Japanese virus isolated by Hotta and Kimura was subsequently shown to be DENV-1 as well. Two more serotypes, dengue 3 and dengue 4, were subsequently isolated from patients with a hemorrhagic disease during an epidemic in Manila, the Philippines, in 1956 (Hammon et al., 1960). Since these original isolates were made, thousands of dengue viruses have been isolated from all parts of the tropics, and from mosquitoes, humans, and nonhuman primates; all fit into the four serotype classification to make up the dengue complex of the genus Flavivirus (King et al., 2012). The recent isolate from Malaysia, however, may increase the dengue complex to five serotypes.

Mosquito vectors

It has been suggested that Ae. aegypti, the principal epidemic vector of dengue viruses, was a New World species. As pointed out by Dyar (1928), Carter (1931), and Christophers (1960), however, Ae. aegypti is most likely of African origin for the following reasons. First, there are no closely related Stegomyia species in the Americas, whereas there are numerous such species of the same subgenus in both the Ethiopian and Oriental regions. Second, Ae. aegypti occurs in Africa as a widespread feral species, breeding in the forest, independent of humans. Although occasionally found occupying natural larval habitats in Asia and the Americas, it is primarily an urban species in both of these regions and only rarely occurs in the absence of man. Thus, current thinking is that Ae. aegypti had an African origin and had adapted to the peridomestic environment, breeding in water storage containers in West African villages prior to the slave trade, which provided the mechanism for the species to be introduced to the New World. Ae. aegypti became closely adapted to humans and was a common passenger on sailing vessels during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. By 1800, Ae. aegypti had already become established in many large tropical cities around the world, especially in port cities in Asia and the New World. In Asia, there is evidence, however, that Ae. aegypti did not become the predominant Stegomyia species in many noncoastal cities until during and after the Second World War (Smith, 1956).

The pre-Second World War distribution of Ae. aegypti is well documented (Carter, 1931; Kumm, 1931; Christophers, 1960). From the records of distribution recorded over many years, it is clear that the species is very strictly limited by latitude, and rarely persists for any time beyond 45°N and 35°S (Fig. 1.2). In the 18th and 19th centuries, Ae. aegypti commonly expanded its geographic distribution to more northern and southern latitudes during the warm summer months, breeding in stored water containers aboard river boats, ships, and other means of transportation, ul...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Part I: History and Epidemiology

- Part II: The Disease

- Part III: The Virus

- Part IV: Virus–Host Interaction

- Part V: Dengue Prevention

- Index