- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

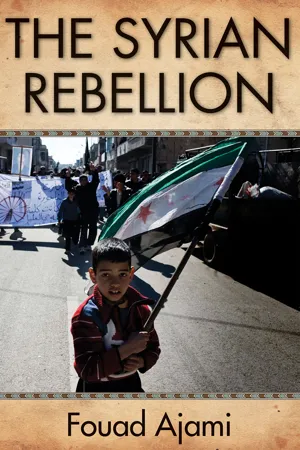

The Syrian Rebellion

About this book

Fouad Ajami offers a detailed historical perspective on the current rebellion in Syria. Focusing on the similarities and differences in skills between former dictator Hafez al-Assad and his successor son, Bashar, Ajami explains how an irresistible force clashed with an immovable object: the regime versus people who conquered fear to challenge a despot of unspeakable cruelty.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Prologue:

The Inheritor

This is as follows: The builder of the family’s glory knows what it cost him to do the work, and he keeps the qualities that created his glory and made it last. The son who comes after him had personal contact with his father and thus learned those things from him. However, he is inferior to him in this respect, inasmuch as a person who learns things through study is inferior to a person who knows them from practical application.

THE GREAT NORTH AFRICAN HISTORIAN, Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), wrote the above of dynasties in his Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Ibn Khaldun had written that prestige in one lineage lasts four generations before it dissipates. It is doubtful whether the Assad lineage is slated for four generations. What mattered as a rebellion broke out in Syria in 2011 was the insight to the relation—the similarities, the difference in skills—between Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar. The father had rigged the succession; fear had done the trick. The lieutenants in the wings, old subordinates and colleagues who had known the father and who had ideas of their own that his death would give them a shot at succession, were bullied and sidelined. There was Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam, a lawyer from Baniyas and a Sunni who was two years younger than Hafez al-Assad, an ally from the very beginning of the Assad reign. There was Minister of Defense Mustafa Tlas, also a Sunni, from Rastan, near Homs. He had served in that position since 1972 and hailed from the officer class, unfailingly loyal to his leader. These and others had been pushed aside in favor of a newly minted “General” Bashar al-Assad, thirty-four-years old when he inherited the realm. This was not the script that the ruler had had in mind. He had groomed his oldest son, Basel. But that son had died in a traffic accident in 1994. The old guard had to submit to and accept this dynastic succession. Khaddam didn’t and ended up making his way to exile and opposition from Paris. Hafez al-Assad didn’t have much time to tutor Bashar, and as Ibn Khaldun and countless others had told us, such skills are not easy to transmit.

“Yalla Erhal Ya Bashar” (“Come on Bashar, Leave”), the crowds had taken to chanting. More poignantly, in Hama, the young people carried placards that read, “Like Father, Like Son.” Back when he had come into power, Bashar had made a good first impression, if only because he was different from his intimidating, stern father. His father had been a peasant boy, born in the Alawi mountains and married into his own community; he had come into the coastal city of Latakia, and he had plotted his way to the summit of political power. So many of Hafez al-Assad’s peers and rivals had fallen to assassins’ bullets or perished in Syria’s cruel prisons, dispatched there by Assad himself. In contrast, Bashar had been the entitled prince, schooled in the best academies in Damascus and with a stint of time in London behind him. He had known no hardship. In the manner of a society eager for deliverance, it was hoped that he would open up the big prison that Syria had become under his father.

Outsiders prophesied good tidings for Bashar. U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who had gone to the Old Man’s funeral in 2000 and met the son, came back with a favorable report: he was a “reformer,” she said, bent on modernizing his country. French President Jacques Chirac took it upon himself to induct the young ruler into the respectable order of nations. Bashar married well, which was his first olive branch to his country. His wife was a Sunni, the London-born daughter of a cardiologist, Fawwaz al-Akhras, who lived in self-imposed exile in London and spoke discreetly of the sins of the old regime. The bride had worked for J. P. Morgan in London and was on her way to pursue a Harvard MBA when she met and then married Bashar. There was talk of a “Damascus Spring” at the beginning of his reign.

Small gestures mattered. Bashar made his way to restaurants now and then without heavy security. He was head of the Syria Computer Society and promised openness in a country where the ownership of fax machines was restricted. Western cigarettes, banned by his father, were now available. There was a boom in tourism and a respectable flow of investments from the Gulf states. Art galleries and five-star hotels changed the drab atmosphere. He released from captivity several hundred political prisoners, and his people could be forgiven the classic hope that if only the “good tsar” knew, if only his palace guard would let him rule according to his wishes, the realm would be repaired and the oppression lifted. But the realm was what it was, the political universe had been closed up. Power had made a seamless transition—from the Baath Party to the Alawis, and then to the House of Assad—from the sect to the family. The young man who was said to thrill to the music of Phil Collins was cut of the old cloth. He, too, like his father, could brook no dissent.

Syrians had puzzled over their ruler’s place in the constellation of power: was he, like his father before him, master of the realm, or a puppet, his strings pulled by mightier powers? To rule Syria effectively, the man at the helm had to have mastery over the four pillars of political power—the Alawite community, the army, the security services, the Baath Party. A renowned journalist and activist, Michel Kilo would maintain as late as 2009 that Bashar dominated foreign policy while the security services reigned over domestic affairs. The answer as to the proclivities of the young ruler was not long in coming. The regime quickly snuffed out the Damascus Spring. There was a thirst for liberty. Syrians long silenced yearned for political argument and debate, it had been so prominent a feature of their political life before the Assad years. A noted intellectual and academic living and teaching in Paris, Burhan Ghalioun recalls the enthusiasm of that moment: civic forums sprouted everywhere, there were fifty new “salons” in the space of a few months, and even villages wanted forums of their own and were willing to run afoul of the security forces. Ghalioun attributes this enthusiasm to the “exceptional thirst of the Syrian middle class for freedom.” One such civic group, the Forum for National Dialogue, headed by Riad Seif, a dissident of high standing and genuine courage, invited Ghalioun to give a public lecture. Seven hundred people showed up, and Baath Party functionaries grew alarmed at the public ferment. People had taken the young president’s claims to openness at face value and had begun to test them. It did not really matter whether the ruler himself had recognized the threats to the autocracy, or whether that perennial “old guard” had drawn a line against these new temptations. The forums were shut down, and dissidents hauled off to prison were given sentences between two and ten years. “I called it a warm day in winter,” a renowned civil libertarian and lawyer, Haitham al-Maleh, said of this false spring. “I was not surprised. Bashar is the son of his father.” The hopes invested in the young ruler were in vain. If anything, Bashar’s rearing had formed an uncompromising autocrat, one perhaps more unyielding than his father. Ghalioun put it well: “When Assad the elder died, I knew his son was going to be more dangerous than his father. His father was a political figure with political connections. He had struggled to reach his position, irrespective of his methods. But Bashar was born into a qawqaa (a shell), with no political experience. I knew he would not be able to respond to a complex society and that he would use violence more than his father. People would say he is more open, European-educated. But I viewed him as a young, inexperienced, out-of-touch crown prince, surrounded by bodyguards and an entourage.”

There came a time when the guesswork about the ruler subsided. This “crown prince” had been bequeathed his kingdom by autocracy—his father’s will, the accidental death of his older brother, Basel, who had been groomed to rule—and it stood to reason that he would defend what he had been given.

An irresistible force has clashed with an immovable object. The regime could not frighten the population, and the people could not dispatch the highly entrenched regime that Assad Senior had built, the most fearsome national security state in the Arab East. In other words, a country confronting the classic ingredients of a civil war, and a sectarian war within. The Syrians who braved it all did not want to be ruled by Bashar’s children in the way they had been ruled by Bashar and their parents by Bashar’s father. As though to foreclose the political universe, Bashar had a son and named him Hafez. The age-old bargain in Arab lands, bread for freedom, had come apart in Syria, more than 30 percent of its people were living below the poverty line, and key sectors of the economy were in the hands of the House of Assad and their in-laws. A proud people wanted something more than this drab regime of dictatorship and plunder.

Hitherto quiescent people were done with the Assad tyranny, and they were ready to pay the ultimate price. The dictatorship alternated savage violence with promises of reform. The protests had begun in mid-March, and the regime was to make what it saw as its big concession—the lifting of the emergency law that had governed the country since 1963. But the tanks and the helicopter gunships were now loose on the population. Syrians were fleeing across the borders to Turkey and Jordan and Lebanon. Amid this violence, the ruler appeared dazed and uncertain. He could not recognize the rebellious people demanding an end to his tyranny. For four long decades, the Assad dynasty, the intelligence barons, and the brigade commanders had grown accustomed to a culture of quiescence and silence. Ruler and ruled were now in uncharted territory. A boy of thirteen from the southern town of Deraa, by the Jordanian border, Hamza al-Khatib would emerge as the emblematic figure of this war between the regime and its people. The boy had been picked up along with a number of his peers. They had committed the unpardonable sin of scribbling anti-regime graffiti on their town walls. His body was returned to his family a month later. He had been subjected to horrific torture, his knees and neck broken, even his genitals severed. In the mind of the dictatorship and its enforcers, this was meant to do the trick and scare people into their private homes. It had worked that way before, but the barrier of fear was broken. That grim deed had strengthened the resolve of those who wanted to be done with the cruel regime. Another notable crime took place in Hama and it was to echo through the country: the body of a young cement layer named Ibrahim Qashoush was dragged from the Orontes River in July. The man’s throat had been cut and his vocal cords ripped out. Torturers and regime enforcers are never subtle. The man had sinned against the order of things by singing a popular protest lyric, “Yalla Erhal Ya Bashar” (“Come on Bashar, Leave”). The silence had been breached, and a lyric would cost a man his life. Clarity came with the repression. The protesters were now saying that they hated the regime and its functionaries more than they did the Israelis they had long hated and maligned. Those with a memory of their country under French rule—and young protesters who were told of this history—now spoke of the respect shown by French forces for the sanctity of mosques. Mosques were then off-limits, a sanctuary for protesters on the run. Now mosques, and even their prayer leaders, were fair targets for the forces of the regime.

It’s no surprise the eruption came in Syria, chronologically, after the upheavals of Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Libya, and Bahrain. The Syrians had taken their time. It was as though a people knew that they were in for a particularly grim and bloody struggle. Tunisia had led the caravan and then stepped out of the way, its upheaval overwhelmed by the protests in Cairo. The Tunisian strongman had made a run for it first, on January 14, 2011. The Egyptian ruler had followed, his reign of three decades coming to an end on February 11. Libya, flanked to the west by Tunisia and in the shadow of Egypt to the east, rose in rebellion on February 17. The date would become, on the calendar of the Libyan rebels, the birth of their new order.

Fittingly, Friday would become the big day of protest. The protesters would give each Friday a name and a theme—Your Silence Is Killing Us, the Friday for International Protection, the Friday of the Free Syrian Army, With Us Is God, and so forth. Forty-two Fridays were to come and go in 2011, and both the regime and the opposition were standing their ground. Bashar, the accidental inheritor of a political realm, now had his own war. He had stepped out of his father’s shadow only to merge with it. If the protesters were discouraged, they didn’t show it. They vowed that 2012 would see the end of this dictatorship.

FROM IBN KHALDUN:

As one can see, we have these three generations. In the course of these three generations, the dynasty grows servile and is worn out. Therefore, it is in the fourth generation that ancestral prestige is destroyed.

Bashar al-Assad did not have to worry about the two generations to come after him squandering ancestral prestige. Ibn Khaldun was a genius, but history moved with velocity nowadays. This dynastic inheritance in Syria was not destined to survive the second generation.

Ibn Khaldun may have been excessively generous with the life span he gave dynasties—from their rise from “savage,” austere beginnings to their descent into ease, luxury, and dissolution. But the great gift of his analysis, and one that unlocks the Syrian present—and so much of political life in the Arab-Islamic domains—was the central notion of asabiyah (solidarity, group feeling, group consciousness). The great North African observer of history saw asabiyah as central to the rise of dynasties and to the building of a dawla (state). “Royal authority and large-scale dynastic power are attained only through a group and group feeling. This is because aggressive and defensive strength is obtained only through group feeling, which means affection and willingness to fight and die for each other.” It was possible, he wrote, to establish royal domination without “religious coloring,” but only barely so. The norm was group feeling buttressed by one of religious propaganda. Here is his central proposition: “Religious propaganda gives a dynasty at its beginning another power in addition to that of the group feeling it possessed as a result of the number of its supporters.” Alawi asabiyah made this Assad regime—the group feeling of a mountain people who had a jumbled mix of persecution and superiority hammered into them by history. It is perfectly consistent and rational for a people to suffer material destitution while still entertaining notions of their superiority to people of means and leisure, and this was at the heart of the antagonism between the Alawi mountain and the Sunni cities. But there was another maxim favored and frequently used by Ibn Khaldun—the common people always follow the religion of their rulers. “The vanquished always want to imitate the victor in his distinctive characteristics, his dress, his occupation, and all his other conditions and customs.”

This was where the Syrian edifice would crack. There was no possibility that the Syrian populace—Islamically devout and in the midst of an Arab-Islamic world awakening to the power of Islam—would follow a community of schismatics. There were cases of young Sunni students in universities, observers tell us, imitating the distinctive speech of the Alawi mountain and coastland. But they were the exceptions. The Alawi dominion was not destined to last. Bashar surely lacked the cunning of his father, but the Alawi odyssey carried within it the seeds of its own destruction.

Next door in Lebanon, the Maronites, another mountain people with an asabiyah of their own, had enjoyed primacy. But their condition and their relation to the communities with which they shared the small country couldn’t have been more different. The Maronite mountain was never an isolated world. The Mediterranean and their national church gave the Maronites wide cultural and political horizons. The Maronite patriarchs recognized the supremacy of Rome in the late years of the twelfth century. Though the Holy See had not always been attentive to this remote people, the religious traffic had enriched the life of the Maronites. A Maronite college in Rome, established in the sixteenth century, trained young clerics in the Roman ecclesiastical doctrine. The Maronites were to prove a gifted people. The literary renaissance in Arabic letters, the so-called age of enlightenment, asr al-nahda, in the late 1800s rested in large measure on the superb abilities of the Maronite writers. It’s true that France had given Maronites favored treatment during the Mandate years. But the Maronites made their own luck when the French quit Lebanon.

The first Lebanese republic (1943–1975) was anchored in a Maronite-Sunni entente. The Maronites did not govern alone, and they didn’t rule by force of arms. Their primacy, if they had it, issued out of their superior educational achievements; their schools were the pride of the country, the destination of choice for the gifted and ambitious young Muslims. There were the lands of al-mahjar (the diaspora communities) in North and South America, and the Maronites were dominant there. From al-mahjar came ideas, social capital, and repatriated wealth. In the Lebanon of the 1950s and 1960s (if I may be permitted a side note of autobiography from my boyhood), the Maronites were envied and admired, and covertly imitated by the other communities. Their schools and monasteries were the institutions of a people proud of their accomplishments. None of this holds true for the Alawis. There was no diaspora that knit them into a bigger world. There was the military and, in time, the Baath Party that brought them out of their solitude.

CHAPTER TWO

Come the Mountain People

HISTORY HAD BEEN UNKIND to the Alawis—their theology perhaps mattered less than their sociology. They were an insular mountain community, impoverished and disdained by the peoples of the cities and plains. They had emerged as a schism within Shiism more than a millennium ago. It was in a tumultuous century—the closing years of the ninth century to the middle of the tenth—that the sect appeared. Mainstream (Twelver) Shiism was in crisis: the eleventh imam had died and his infant son, designated as the mahdi (the redeemer), had vanished before the eyes of ordinary men to return at the “end of time” and fill the earth with justice. Pretenders rose amid this uncertainty, and charismatic preachers filled the void, working their will and conceptions on religious dogma. The adherents of this sect moved between Iraq and Syria, and then made their home in the massive mountain range in northern Syria. For several centuries they went by the name of Nusayris and gave their name to the mountain range they inhabited. Their principal theologian, a preacher by the name of Abdullah al-Khasibi, proclaimed the divinity of Imam Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law. Theirs was a syncretistic theology that included Neoplatonic, Gnostic, Christian, Muslim, and Zoroastrian elements. For both Sunni and Shia Muslims alike, the Nusayris were ghulat (extremist) exaggerators who carried the veneration of Ali beyond the bounds of Islam.

A thorough study of the heterodox Shia cults, Matti Moosa’s Extreme Shiites: The Ghulat Sects sets the place of Imam Ali in the cosmology of the Nusayris: “To the Nusayris, Ali Ibn Abi Talib, blood cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, is the last and only perfect one of the seven manifestations of God, in which the Islamic religion and its Sharia law have been revealed. He is the one who created Muhammad and taught him the Quran. He is the fountainhead of Islam. He is God, the very God of the Quran.” The break with Islam is total. To the Sunnis, Ali was one of the four Guided Caliphs (successors to the Prophet), husband of Muhammad’s daughter Fatima, father of the Prophet’s grandchildren. His place in the order and the history of Islam is secure and beyond reproach. To the Shia, Imam Ali is the beloved man around whom Shiism had crystallized. He had been robbed of his right to inherit the Prophet’s mantle, he had been made to wait for his turn at leadership, and three caliphs had gone before him. He had come to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Charles Hill

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Chapter One: Prologue: The Inheritor

- Chapter Two: Come the Mountain People

- Chapter Three: The Time of the Founder

- Chapter Four: False Dawn

- Chapter Five: Boys of Deraa

- Chapter Six: The Phantoms of Hama

- Chapter Seven: The Truth of the Sects

- Chapter Eight: Sarajevo on the Orontes

- Chapter Nine: The Stalemate

- Chapter Ten: A Note on the Exiles

- Chapter Eleven: Fragments of a Past Mourned and Dreaded

- Afterword

- Source Notes

- About the Author

- About the Hoover Institution’s Herbert and Jane Dwight Working Group on Islamism and the International Order

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Syrian Rebellion by Fouad Ajami,Fouad Ajami in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.