eBook - ePub

An Agenda for Economic Reform in Korea

International Perspectives

This is a test

- 600 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An Agenda for Economic Reform in Korea looks at Korea's economic problems from the perspective of the American experience with economic reforms and sheds new light on the problems of economic reform facing nations all over the world. The authors examine such issues as corporate governance, social welfare, labor relations, and other pressing challenges—and suggest a new vision for the Korean economy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access An Agenda for Economic Reform in Korea by Kenneth Judd, Young-Ki Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Overview

Dong-Se Cha and Sang-Woo Nam

1

The Korean Economy in Transition

Legacies and Vision for the 21st Century

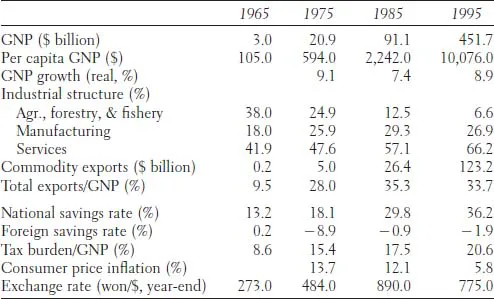

The Korean economy has achieved an unprecedented growth in the last three decades or so. Between 1965 and 1995, the per capita GNP increased from US$105 to over US$10,000. The share of agriculture in GDP decreased from 38 percent to less than 7 percent during this period, while exports recorded a substantial increase, from US$0.2 billion to US$123 billion with 70 percent accounted for by heavy and chemical products. And life expectancy rose from 57 years to 71 years.

Many different elements have contributed to Korea’s rapid economic growth. The first is a literate population capable of learning skills quickly–which played a key role in export-oriented (labor-intensive) industrialization during the earlier phases of development. Korea achieved universal primary education as early as the mid-1950s; later, in response to the steady upgrading of the industrial structure, vocational and technical education and training were strengthened, and college student quotas were greatly increased. In the Confucian tradition, Korean parents are willing to make sacrifices for the education of their children, and workers have been industrious and disciplined in their drive to improve their socioeconomic status.

Second, Korea has had a strong leadership commitment to economic development and capable, devoted bureaucrats. The number one promise of the military government of General Chung Hee Park, which came into power by a coup in 1961, was, “We will liberate people from poverty.” Delivering this promise was the only way to justify and consolidate the legitimacy of the regime. Civil servants were and are generally well respected (again, a Confucian characteristic), and the bureaucracy was able to attract people who were not only capable and devoted, but also relatively scrupulous. With the success of government-initiated economic progress, public confidence in the government has been strong in Korea.

A third element has been the ambitious entrepreneurs. Though not well respected by people in general, who tend to believe that they accumulated their wealth by means of government favors such as exclusive import licenses and preferential loans, Korean entrepreneurs have proved themselves to be very dynamic and forward looking. They have aggressively exploited overseas markets for trading, local construction, and, more recently, investment. Domestically, Korean business groups have diversified extensively into a number of industries and have dominated in many markets, particularly manufacturing. In spite of high market concentration, the groups have maintained a competitiveness that has been favorable to consumers. With the diversification of business risk, entrepreneurs have been bold and effective in technology and manpower development, thereby generating positive externalities for the society.

Finally, and perhaps most important, Korea’s economic performance owes much to government policies. The takeoff of the Korean economy began with the export-oriented industrialization strategy in the early 1960s. This strategy enabled Korea to make the best use of its available resources, mainly labor, and overcome the limitation of the small domestic market. In the 1970s, the emphasis on heavy and chemical industries, although it had some not altogether happy side effects, significantly contributed to upgrading Korea’s industrial and export structure. Policy emphasis after the 1980s shifted to promoting the role of the market in resource allocation by reducing direct government intervention and fostering competition (see Table 1).

This strategy of export-oriented industrialization enabled the Korean economy to have an admirable takeoff in the early 1960s. Entering the 1970s, an unfavorable external environment led Korea to undertake heavy and chemical investment projects in order to upgrade the export structure and strengthen defense capabilities. Credit, tax, trade, and exchange rate policies were heavily distorted by the government to favor some sectors against others. At the same time, government intervention proved to be very costly to the economy, particularly because of the worldwide recession caused by the second oil price shock. Many favored projects continued to decline, the financial sector remained weak and inefficient, and rapid increases in bank loans accelerated inflation. In reaction to these setbacks major policy efforts in the 1980s, including strong antiinflation programs, reform of the industrial incentive system, trade liberalization and financial liberalization, were largely successful in correcting macroeconomic imbalances and strengthening the industries.

TABLE 1 Performance of the Korean Economy, 1965–1995

During the mid-1980s, a favorable external environment, particularly the strong Japanese yen, resulted in rapid export growth and a sizable surplus in the current account. The surplus, however, invited strong foreign pressure to further open the domestic market and drove up the Korean won. The historic June 29 Declaration of Democratic Reform in 1987 unleashed workers’ demand for wage increases and better working conditions. Substantial wage hikes coupled with strong domestic demand and progress in import liberalization have worked together to lower Korea’s current balance. A sense of crisis has recently become widespread among Koreans. Many small and medium-sized firms in light manufacturing have gone bankrupt because they could not compete with products from China and other developing countries in either domestic or foreign markets. For their survival, some have moved their factories offshore. With the weakening Japanese yen, as well as a deteriorating world market for semiconductors, steel, and petrochemicals, exports stagnated in 1996 and early 1997. The current account deficits in 1996 reached almost 5 percent of GDP.

Korea’s vision for the next few decades is to achieve an advanced economy and a unified nation. In realizing these objectives, it faces some stiff challenges: weakening competitiveness in the midst of global competition, growing burdens to bear for improvements in the quality of life, and the road to reunification with North Korea. Along with these challenges, there will be promising opportunities from new markets, enhanced technological capabilities, and other efficiency improvements.

This paper describes the legacies of Korea’s development strategies since the early 1960s. Then, it discusses the challenges and opportunities Korea faces and the strategies being adopted to realize its vision for the twenty-first century.

Legacies of Past Decades

Korea’s development strategies, either explicit or implicit, during the last several decades have largely shaped the characteristics of the Korean economy and economic management. Among the characteristics are (1) preoccupation with growth and less concern with social development; (2) concentration of economic power around large business groups, which generally weakens the position of small and medium-sized firms; (3) immature industrial relations; (4) a weak financial sector, the development of which has been constrained in the government drive for industrialization; (5) regional concentration of industries; and (6) government-initiated development with a multitude of regulations that continue to restrict business activities. Among these, the first three seem to be of the greatest consequence in determining the nature of the Korean economy.

CONCENTRATION OF ECONOMIC POWER AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

With the extensive diversification of their business interests, large business groups (chaebols) in Korea were able to be aggressive in developing new products and markets and undertaking other risky projects. The chaebols have been efficient in overcoming the principal-agent problem, since the chairman (owner-manager of the group) closely monitors the managerial performances of the member corporations. With shared information, know-how, and resources among member firms, chaebols also had a better chance to adjust to changes in the factor markets and expand their economies.

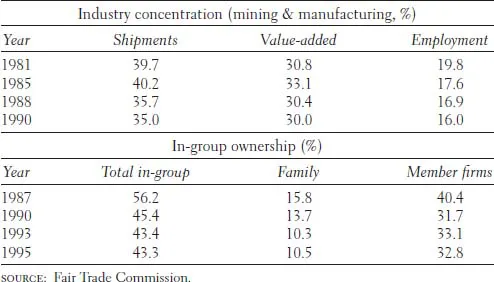

There has, however, been increasing concern over the concentration of economic power in the chaebols. Not only is there fear that the concentration of economic power could lead to increased political power and distort government policies, the failure of chaebols could also be costly in terms of moral hazards and sacrifices of the financial sector. Second, many chaebol-affiliated corporations often have a market-dominating power, which, together with their extensive business diversification, draws them into practices that constrain fair competition and abuse conflicts of interest for the benefit of the entire group. Third, chaebols may infringe on the interests of smaller firms and minor stockholders. With cross-repayment guarantees and shareholding among member corporations, chaebols tend to limit the access of smaller firms to credit and dividend receipts for small stockholders. Finally, many analysts have serious doubts about the internal efficiency of chaebols. Cross-subsidization among member corporations is likely to cause inefficient allocation of resources, and managerial control concentrated in the chairman often leads to rigidity, red tape, and the absence of any countervailing power to check the dogma and authoritarianism of the owner-manager.1 (Table 2 shows the concentration of ownership in the thirty largest chaebols, 1981-1995.)

On the whole, Korea frowns on the mix of banking and commercial businesses, believing that this mix (for example, chaebols owning banks) would lead to concentration of economic power with undue influence over the political process, conflict of interest abuses, and instability in the financial system. These are valid concerns when entry into financial services is restricted or banking services have any subsidy elements. Even when financial markets are competitive and allow free entry, the mix of banking and commercial products increases the likelihood of conflicts of interest if the firm has market power in the commercial product. It is probable, however, that the opening of the domestic markets and industries, including banking, to the world, will make it increasingly difficult for any firm to have market-dominating power. Thus, the risk of mixing banking and commerce should not be as serious as before.

TABLE 2 Industry Concentration and Ownership, 30 Largest Chaebols

A related corporate governance issue is the bank-business relationship. Unlike Japanese main banks or German house banks, Korean banks do not have an intimate relationship with their corporate clients. Japanese main banks reduce information asymmetry by serving as the leader of loan syndication and as the delegated monitor for other creditor banks. Mutual shareholding between main banks and their corporate clients is an important feature of the Japanese main bank system. When a firm is in financial distress, its main bank, as both creditor and shareholder, may also intervene in corporate management. However, being basically exclusive and secretive, the main bank relationship also has elements of inefficiency and unfairness.

Korea’s principal transactions bank system was introduced to correct the skewed allocation of bank credit toward chaebols. The principal transactions banks, implementing the credit control system and other regulations of the government toward large business groups, have functioned as de facto suborganizations of the supervisory authorities. Given that Korean financial markets are still far from being perfect, with large information asymmetries, the role of banks as credit evaluators and monitors of corporate management could be critical. Thus, a closer and more autonomous bank-client relationship may be promoted by eliminating institutional constraints and improving the policy environment that has suppressed the development of such a relationship.

INADEQUATE SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND DISTRIBUTIVE INEQUALITY

In spite of significant improvement in the people’s standard of living over the last three decades, it is widely perceived that social development has lagged behind economic growth in Korea. This gap between economic growth and social development is primarily due to Korea’s development strategy of putting the highest priority on growth and the belief of the leadership that creating jobs is the best welfare. Because limited resources have been allocated with a view to maximizing short-run results, the share of government expenditures for social development, including health, housing, and social security and welfare, is still very low.

Industrial accident insurance and public assistance programs were in existence even in the 1960s, but the expansion of the social security system has been slow. An extensive medical insurance scheme was introduced in 1977, and in 1988 a national pension system and a minimum wage regulation were put into place. Employment insurance was introduced in 1995. All these programs have to be further broadened and integrated to reach the most needy people and to redress the lack of cohesion and harmony among them.

The slow development of the social security system in Korea has been due in part to traditionally strong family ties. Korean parents make great sacrifices to give their children a good education, with the implicit expectation that the children will take care of them later on. This strong sense of solidarity based upon an extended family concept has acted in the stead of public social security programs. Mutual aid is also provided among brothers and sisters, who are often ready to help each other in times of hardship or emergency. But this East Asian Confucian ethic of placing great emphasis on the family rather than on individuals is now on the ebb. With growing industrialization and urbanization, the modern family in Korea is typically a small nuclear family, and many parents can no longer rely on their children for security in their old age. This change calls for a substantially enhanced role for the social security system in Korea.

The experiences of advanced countries show that, once a welfare program has been put into place, it is very difficult to reduce its benefit level. The ambitious pursuit of a welfare state may weaken people’s motivation to work and the dynamism of the private sector, and accordingly adversely affect the vitality of the economy. In Korea especially, a greatly expanded social security budget would be not only an exorbitant fiscal burden on the government but also a social wedge–it could deepen intergenerational conflict and weaken family solidarity and the spirit of mutual aid in local communities. Therefore the great challenge is to develop a balanced social security and welfare system that is consistent with social equity and economic efficiency but also preserves desirable long-held family and communal values.

The distribution of income in Korea is relatively equitable compared with that of most developing countries. As Table 3 shows, in the 1960s particularly, the export-oriented development strategy seems to have contributed to equitable income distribution through the rapid absorption of surplus labor from rural areas into labor-intensive urban manufacturing. This favorable trend was interrupted during the period of heavy and chemical industry promotion in the 1970s, when heavily subsidized credit provided mainly to chaebols and other large firms widened wage disparities and led to drastic rises in rents and real estate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Booktitle

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Overview

- Part II. Business Organization and Competition Policy

- Part III. Corporate Governance

- Part IV. Social Welfare

- Part V. Distribution of Income

- Part VI. Labor and Industrial Relations

- Part VII. Property Rights and Economic Development

- Part VIII. Culture and Economic Development