![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Great Divergence?

Kori Schake and Jim Mattis

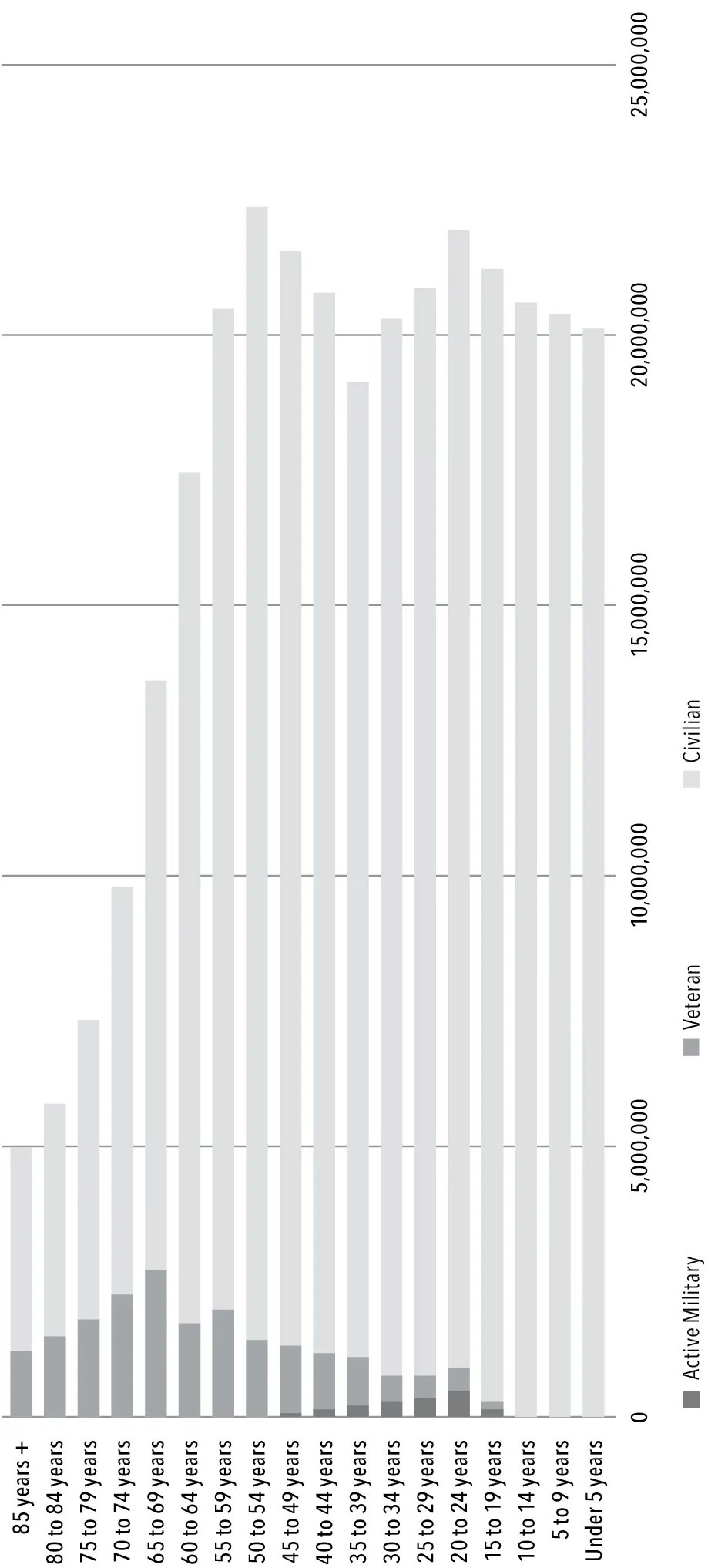

We initiated this project out of curiosity about whether, after forty years of an all-volunteer force, a small force relative to our overall population, and twelve years of continuous warfare, the American public was losing connection to its military. Our concern was not loss of connection in the sense that preoccupies academic experts on civil-military relations in the United States—a military insubordinate to civilian control. We saw scant evidence of that in either our policymaking or military experience. Rather, with less than one half of one percent of the American public currently serving in our military (see figure 1.1) and with the high pace of deployments for significant elements of our fighting forces, we were interested in the cumulative effect of having a military at war when the broad swathe of American society is largely unaffected. Whether or not the different experiences of our military and the broader society amount to a “gap” and whether such a gap is adequately defined seemed worthy areas to delve into.

FIGURE 1.1 United States Civil-Military Population Pyramid

Courtesy of Tim Kane. (Data from United States Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey,” 2012, http://www.census.gov/population/age/, http://www.census.gov/hhes/veterans/data/, and from Defense Manpower Data Center, 2014 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community, 2014, http://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2014-Demographics-Report.pdf, p. 35.)

Source: Tim Kane, The Hoover Institution, based on US Census, ACS, and DMDC (most recent data as of 2015.

The untethering of our military from our society could be damaging to both in many ways. Some thought that our civilian society would become perhaps more willing to engage in wars and certainly more hardened to the costs of warfare from which they have the luxury of being insulated. Anecdotes indicated that public inexperience with veterans could complicate their reintegration into society, even cause them to be perceived as a threat to the broader society. With little experience of warfare in the general population, the public may have scant appreciation for what is needed to win our wars or become contemptuous of the military virtues necessary for winning on the battlefield when those virtues are out of synch with the values of our civil society. Elected political leaders without military expertise may have trouble crafting strategies for the successful conduct of our wars. The military could even come to consider itself a society apart, different from, and more virtuous than, the people they commit themselves to protecting, like praetorian guards at the bacchanalia, as one soldier described it. Or our military could begin to feel that society “owes them something,” fostering entitlement attitudes that would chip away at the culture essential to retaining warriors in our military forces. We were concerned above all about suggestions that the rest of society has simply become apathetic to the issues that dominate the consciousness of those who have been putting their lives on the line for the rest of us in the wars our country is fighting.

While major surveys of public attitudes occasionally focus series on veterans’ issues and include some questioning in these areas, we were surprised at the dearth of systematic data or quantifiable indicators to gird analysis about the American public’s understanding of, and relationship to, its military. After two extensive polls and cross-disciplinary exploration, we are greatly relieved to say that the concern about the American public losing connection to its military was not substantiated by research conducted for this project. The common perception of divergence is wrong. Public opinion surveys conducted as part of this study strongly suggest that while the American public is not knowledgeable about military issues, its judgment is fundamentally sound, and its concern is unabated for the soldiers, sailors, airmen, coastguardsmen, and Marines who fight the nation’s wars.

Whatever they think of the wars our country is fighting, Americans no longer blame their military as many did during the Vietnam War. The enormous respect Americans have for our military is obvious in ways large and small throughout society: the near-universal convention of thanking men and women in uniform for their service; the now-standard practice of tributes to our military during major sporting events; airlines’ policy of boarding military passengers first (without apparent exasperation by other travelers); and—especially—the overwhelming support in Congress for increasing military pay and benefits, even when the military services themselves would like to curtail the rate of growth. No one gets elected in America running against the troops. Foreign troops serving in America are often amazed at the affection Americans demonstrate for our military personnel.

In this way, the broader society reflects the distinction prevalent in the military itself between personal judgments about a war and the commitment to fighting it. Choosing war is the business of elected politicians in America; fighting war is the business of our military. The sturdiness of this principle on both the civilian and military sides of the equation goes a long way to explaining the affection Americans now have for their military, even though less than 16 percent of Americans served or had a family member serve since 9/11.

The American military’s continuing function as a conveyor belt into the middle class is another strong source of public affection. Strong majorities of both the public and elites consider the American military one of the few remaining reliable means of economic advancement, especially for minorities and the poor. As an institution, it is also considered fairer than virtually any other: it clearly defines and rewards merit. Our research revealed that these long-standing conventions still have powerful resonance with the American public.

The surveys identified, however, many gaps between the American public and its military. We wondered whether some of these gaps make public support for the military broad but shallow. In other words, support for the military is an easy social convention because it demands little from the broader populace. We also explored whether some gaps could in time erode important elements of America’s beneficial civil-military relationship. Moreover, some operant gaps appear not between civilians and the military but between civilians and civilian elites or between civilians and governmental elites, with concomitant effects for the military.

Research Questions

Reviewing the literature on civil-military relations and utilizing our experience in defense policy and the military, respectively, we identified several initial concerns for exploration in the surveys.

Ignorance

Does the public have a basic working knowledge of the military? Does their lack of knowledge lead to worrisome misconceptions—for example, that all veterans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), making them potentially dangerous? Knowledge differences could also affect recruitment and make the public less empathetic about the demands of military life. Does the differential level of knowledge cause the public to be too deferential to military views or cause the public to believe the military is insufficiently deferential to civilians on issues properly decided by suits rather than uniforms?

Public ignorance could also affect the choices political leaders make about warfare: whether to use military force at all, whether to adopt an approach of overwhelming or incremental force, how much political capital to expend on war efforts, whether they face political reversals for escalating costs or failure to achieve their war aims. It can also lead to dramatic and rapid collapses in public support for war efforts. The relationship is interactive: the less informed the public, the greater latitude governmental elites have to avoid electoral consequences for the material and human cost of strategic failure and the more likely public support is to be erratic and quickly eroded.

Strategy Differences

Is there a different approach to making strategy as the result of fewer military veterans’ involvement at high civilian policymaking levels? Before 9/11, it was believed that civilians have a more relaxed view of threats than does the military; since 9/11, scholarly concern has shifted to the way civilians can be too willing to use military force while policymakers focus on civilian opinion and may not understand how to use military force effectively.

Several studies suggest a “veteran advantage” in the making of policy; namely, that veterans are believed to be more hesitant to use military force than civilians. Civilians tend to overstate what military force can achieve, to assume a wider margin for error than those with knowledge and experience from military service, and to lack the analytic discipline essential to developing clear and achievable war aims. Moreover, in a political culture with wide acceptance for the use of military force, veterans are better positioned politically to withstand public pressure favoring it. But military leaders often try to leach the politics out of political decision making in order to better analyze problems and develop strategy; this can lead to “perfect” solutions impractical for consideration by elected officials whose portfolios are broader than the military mandate alone.

Isolation

Because of its smaller size and how little the wars affect the general public, is the military growing more distant from society? Some of the impediments to routine interaction between civilians and the military are the result of budget or operational choices, such as consolidating military forces on fewer larger bases. Some are a consequence of base security or convenience. The result is seclusion for many military families from nearby support in the broader community and less understanding of the demands of military life by civilians.

Most civilians, for example, would have little idea of how to comfort a military family grieving a loss—something that was a much more common experience when our military was larger and service compulsory. Many well-intentioned Americans cannot even find a thread of conversation when discussing military service with a veteran other than asking about PTSD or sexual harassment in the case of female vets. This is potentially a two-way problem: veterans may not want to dwell on their wartime experiences or let such experiences define them in the eyes of society.

Cultural Differences

There is a fundamental difference between military rank structure and the egalitarian culture of America. This sometimes leads civilians without personal familiarity with the military to believe military service is “only about following orders.” There is also among some civilians the temptation to treat warfare as just another arena of politics, with public indifference giving latitude for the imposition of social choices—conservative or progressive—uninformed by the grim exigencies and atavistic demands of warfare. This can translate into a perceived lack of respect by civilians in a military culture steeped in respect.

The culture gap can also lead to difficulties in military recruitment and the reintegration of veterans. Is the public sensitive to the military’s concern that too great a focus on benefits may not bring into the military the types of people the military believes it needs? It can also lead to service members and their families undervaluing the well-intentioned gestures civilians make toward them (for example, yellow ribbons or verbal thank-yous), mistaking unfamiliarity for empty tokenism.

The perception is widespread in the military that civilians are insensitive to its culture—more than insensitive: intolerant. Is our military ideologically and socially out of step with the rest of society? Does the public appreciate that values and practices in the military considered old-fashioned and even out of step with the broader society are considered by many in the military to be integral to their fighting functions in defense of that society? Will a progressive society continue to invest in and connect itself to a military whose requirements for success on the battlefield demand attributes fundamentally at odds with those of the society it protects? If not, is a war-winning military sustainable in a society in which war’s gruesome realities must be reconciled to an operant degree with the larger society’s human aspirations?

Undermining Military Effectiveness

Many of the policies civilians are most eager to change about the military are perceived by civilians as social in nature: the inclusion of women in the infantry, and allowing homosexuals and transgender people to serve openly in America’s military forces, for example. The public may perceive them as civil rights issues; the military by and large does not. In fact, there is concern in the military both about distrust among junior rank...