- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Jewish life through the legends created and narrated in Safed in the sixteenth century.

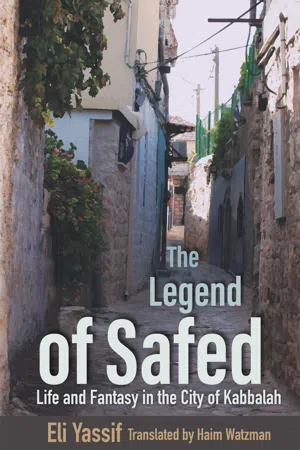

In 1908, Solomon Schechter—discoverer of the Cairo Geniza and one of the founders of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America—published his groundbreaking essay on the city of Safed ( Tzfat ) during the sixteenth century. In the essay, Schechter pointed out the exceptional cultural achievements (religious law, moral teaching, hermeneutics, poetry, geography) of this small city in the upper Galilee but did not yet see the importance of including the foundation on which all of these fields began—the legends that were developed, told, and spread in Safed during this period. In The Legend of Safed: Life and Fantasy in the City of Kabbalah, author Eli Yassif utilizes "new historicism" methodology in order to use the non-canonical materials—legends and myths, visions, dreams, rumors, everyday dialogues—to present these legends in their historical and cultural context and use them to better understand the culture of Safed. This approach considers the literary text not as a reflection of reality, but a part of reality itself—taking sides in the debates and decisions of humans and serving as a major tool for understanding society and human mentality.

Divided into seven chapters, The Legend of Safed begins with an explanation of how the myth of Safed was founded on the general belief that during this "golden age" (1570–1620), Safed was an idyllic location in which complete peace and understanding existed between the diverse groups of people who migrated to the city. Yassif goes on to analyze thematic characteristics of the legends, including spatial elements, the function of dreams, mysticism, sexual sins, and omniscience. The book concludes with a discussion of the tension between fantasy (Safed is a sacred city built on morality, religious thought, and well-being for all) and reality (every person is full of weaknesses and flaws) and how that is the basis for understanding the vitality of Safed myth and its immense impact on the future of Jewish life and culture.

The Legend of Safed is intended for students, scholars, and general readers of medieval and early modern Jewish studies, Hebrew literature, and folklore.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1

Voices Rising from Safed

Wonderful, Wretched Safed

And I found a holy community here in Safed, because it is a great city of God, a city full of wisdom [or Torah], close to 300 great rabbis, all men of piety and action. And I found eighteen yeshivot in Safed, may it be built and established quickly in our day, and twenty-one synagogues, and a great house of study with close to 400 boys and young men. . . . And on the eve of every new month, until midnight, they act as on Yom Kippur, imposing on themselves a prohibition against work, and all the Jews gather in the one large synagogue . . . and pray an awe-inspiring prayer to God until noon, and sometimes devote the entire day to God in prayer and sermons. And the Gentiles who live on the soil of Israel are all submissive and subservient to the holiness of Israel. . . . Other than this, I found the entire Holy Land full of God’s blessing and plentiful and inexpensive food beyond measure and estimation and telling . . . which even in its destruction produces fruit and oil and wine and silk for a third of the world, and [men] come in ships from the ends of the earth, from Venice and Spain and France and Portugal and Constantinople, loaded with grain and olive oil, raisins and figs and honey and silk and soap, good as the sand on the beach. We buy wheat as clear as the sun . . . and olive oil . . . and sesame oil and sesame that is as sweet as honey and has the taste of manna . . . and wine, whoever buys grapes at the time of harvest and stores them in the press . . . as well as spirits of mead . . . and bee honey . . . and grape honey . . . and raisins . . . and dried figs, chickens, very cheap eggs . . . and fish . . . sometimes very cheap. And inexpensive rice and many varieties of legumes and lentils like you have never seen and which taste like nuts, cheap. And all kinds of jams and countless good vegetables that taste like nothing you have ever tasted can be found all the time, throughout the year, in the summer and winter, almost at no cost, in addition to good fruit, carobs, oranges, lemons, melons, and watermelons that taste like sugar . . . and also healthy and clear air and healthful water that lengthen one’s days. For this reason most inhabitants, almost all of them, live long lives, eighty, ninety, even one hundred years. . . . And this is the sign, overseas almost all people and small children are full of boils on the knees and thighs, and in the Land of Israel, thank God, there is not even one person suffering from boils, neither children nor adults; instead all are as clean as gold, thank God.2

Here in Safed we established a holy fellowship and gave it the name Sukat Shalom, and many have gathered to return [to God] with a full heart. From time to time the head of the court also preaches to each community on repentance. Also in each single fellowship the comrades listens together. The material days are sealed, and pound like the sea on the Torah and on the service [of God].4

And before we tremble and shout our wounds on the land that God has cursed, we will tell just one of the thousands of evils and sorrows that have raged on us, because they are uncountable, only one evil out of many, because they are more than the locusts. . . . God and Israel knows, and Israel knew, that we have declined from the beginning, all earlier days were better than these. . . . For there is not even a bit of relief in the Land of Israel, which God gave us through tribulations, sustenance for the hungry and to pay the poll tax to those who hate us, and all sorts of cataclysms and disasters and false charges by wayward officials, small and large, and all sorts of taxes they afflict us with, legitimate and illegitimate, to the point that the Hebrews has been depleted of people; they have gone down to the roads and gates, broken, both the rich and the poor destroyed in Zion . . . for we are wearied by the many tribulations and evils and can no longer withstand them, but the land is miserable, the land has crumbled, the graceful land roars like a lion, because its mourners has become frequent, its agony doubled. . . . A very heavy famine [has befallen us], unlike any before; there is no sustenance. . . . There are no buyers and no sellers, the currency no longer buys anything, the poor have no work, and the penniless seek employment but there is none . . . hungry and thirsty, beaten, weeping and screaming, dragged, hidden and imprisoned, because the city is wretched, its sons impoverished within it these many days . . . and all the people weep from end to end, these weep and those weep, the rich weep and cry out that the middle ones who ate up all their money and impoverished [them], and the middle ones cry out from the multitudes who have plundered them and thus become poor, as if they were dead, and the poor who always perished in the city as eternal dead. . . . The leaders and wealthy have left the city in full view of all, and the ears ring in the streets and roads voices upon voices, frenzied and frightening, between one man and another, between man and wife, between father and daughter, quarrels and clashes on behalf of their obligations and accounts . . . and in their bitterness they seize and drag them and raise a deadly hand against them and interrogate [them], and one beats the other with a stone or a fist. . . . Because they have walked the streets of Safed, may it be built and established quickly in our day, and all those who knew it from ancient times and have turned to it and were ashamed [because of its situation], alas, lonely sits the city once great with people, how has it been overthrown. Because from such a multitude a fissure could have opened up between the walkers on its streets, but now it is reviled and ravaged, bereft of its children, sitting bereaved and forlorn. . . . Because but a few have remained in the city and there is no counting their tribulations, their faces are blacker than soot, they are not recognized in the streets, none comes or goes because those who go out and those who come in have no respite from troubles . . . for there is no bread throughout the land, and even if God were to endow the land with bread, in our house there is no bread, because there is no business, as the clothing trade has ceased, which was the mother of all life, from which both rich and poor lived, and without it we are all dead. . . . Then all wept. . . . And in their horror, as they wept, they turned their faces to the city’s sages and said to them, your eminences, why did you leave your honor, for do we not remember the God-fearing sages who came before you, with all their troubles and their age on the troubles of their flocks and cast their souls before them to save them from thunder, and you are all silent on your watches.6

Voices from Outside

Discord and Strife

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Voices Rising from Safed

- 2. The Myth and Its Disenchantment

- 3. In Fields and Wilderness

- 4. And He Woke and It Was a Dream

- 5. Sin Crouches at the Door

- 6. And He Had Knowledge About Everyone

- 7. Life and Legend

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index